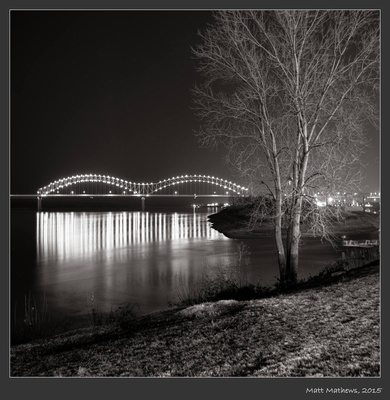

Ironwork, Harahan Bridge, Memphis, Tenn., 2019

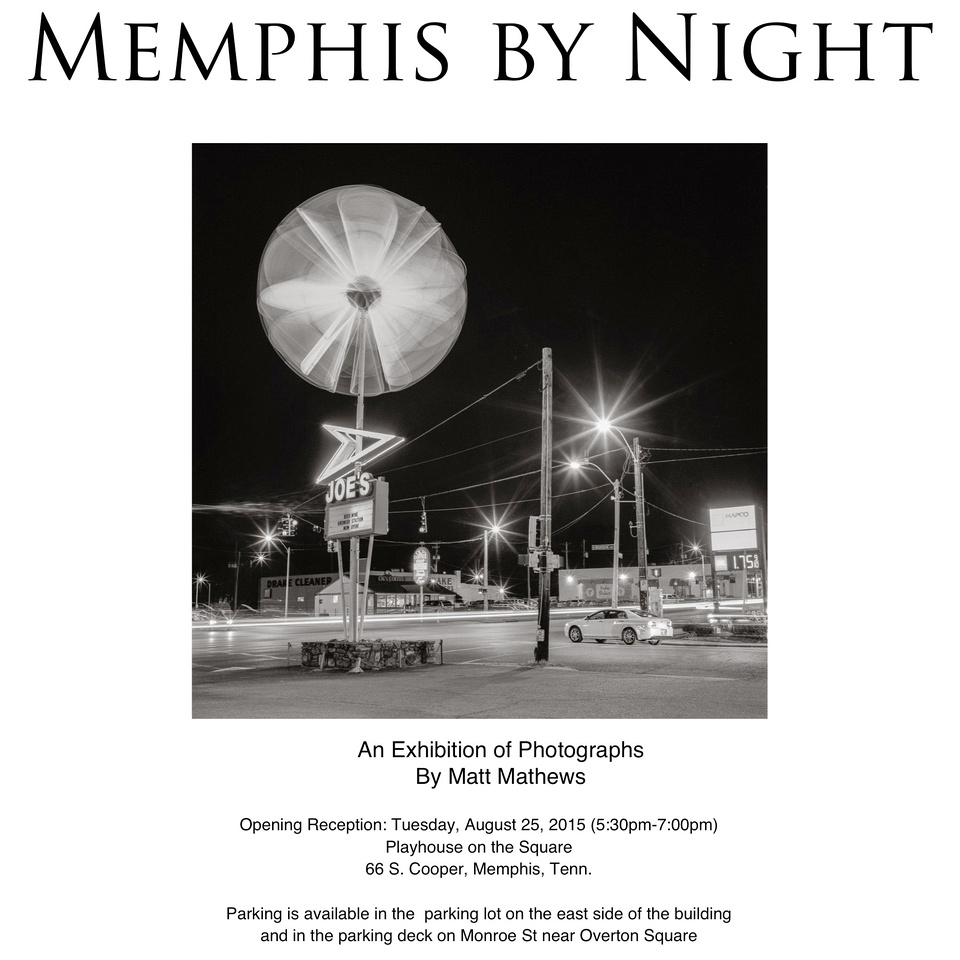

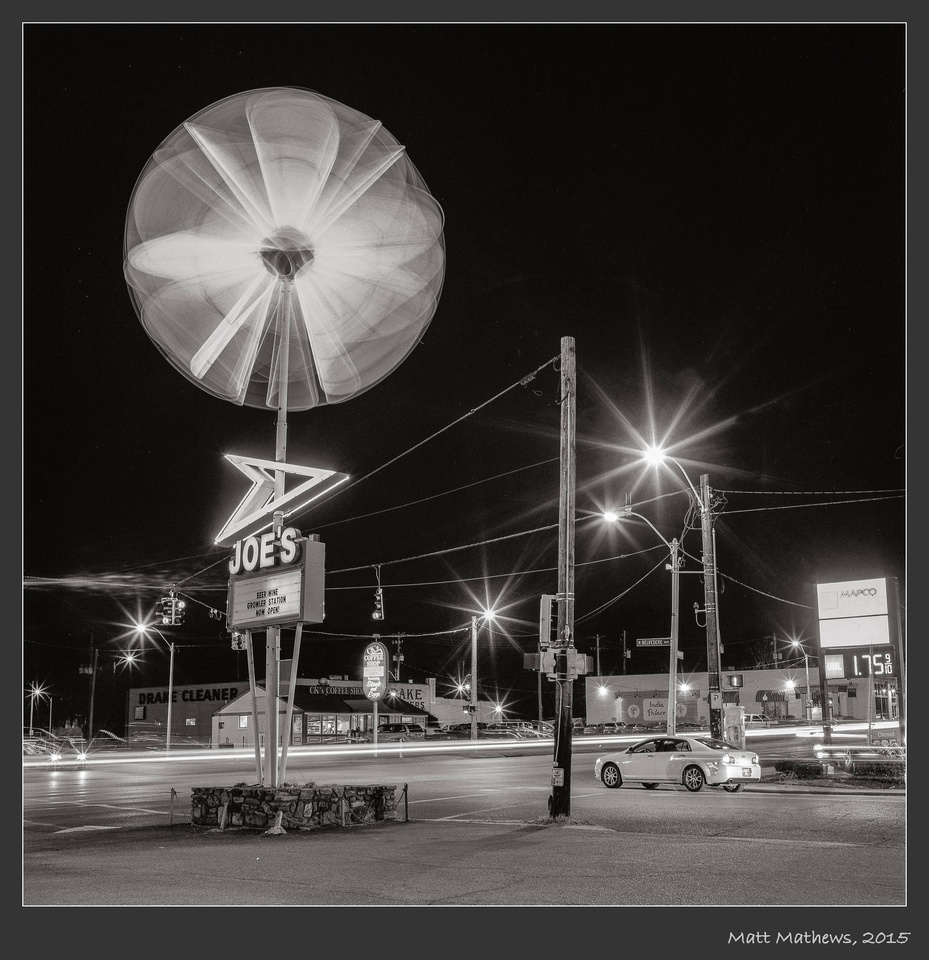

When asked about what makes photographs "good," many photographers will say that they "must tell a story." The idea of pictures telling stories is a powerful one. It reached its zenith in the heyday of the "picture magazines" of the mid-twentieth century, Life and Look, for example. In these magazines, one found "photo essays," carefully sequenced series of photographs that aimed to move the viewer through a visual narrative and plot with a beginning, middle, and end. When done well, such photographic essays do indeed "tell a story," and they often do it better than words alone.

But I don’t think that all good photographs "tell a story." Some do, but not all. In fact, I have never found the metaphor of storytelling the most helpful one when it comes to photography. Instead, I prefer to think of my photographs and most photographs made by others as visual poems.

Poems are very different from stories. They are highly concentrated forms of expression that use an economy of means to convey complex meaning. Generally speaking, poems don’t emphasize moving the reader through a plot with character development, conflict, and resolution. Narrative movement through time is not at their center. They are more lyric than epic, often emphasizing the seemingly insignificant but telling detail present in an evanescent moment of life. And even when we string together a series of photographs, they are less like a story and more like an anthology of poems, bound together more loosely than a plot.

Poems are also different in that they rely more heavily on the evocative and suggestive, offering through their use of concentrated language a multiplicity of possible meanings. Hence, we see the poet’s predilection for metaphor and word play. What photographer Brassaï said of pictures holds equally true for poems, they should “suggest rather than insist."

But at bottom, the concentrated use of words and the evocative power of poetry are intimately connected to the importance on form, the rigorous organization of discrete elements into a coherent pattern in which the whole is greater than the sum of the parts. Form is the integrative arrangement of disparate elements that make possible beauty. In poetry, form is carried in meter, rhyme scheme, and word sound. These form the skeletal structure on which the flesh of metaphor and meaning hang. While all successful art embraces form there is an unusual intensification and surfacing of it in poetry. In the poem, form rises from the depths and floats on the surface to be more easily seen, heard, and felt.

Photography shares with poetry this intensification and surfacing of form in service of concentrated, evocative meaning. The form of photographs is carried in the symmetry and proportionality of the relationships between the elements included in the photographic frame. The artful use of lines, the deliberate placement of balancing tonalities across the frame, the repetition of shapes and their arrangement into patterns, for example, mirror the intensification and surfacing of form achieved in poetry through meter, rhyme scheme, and word sound. And as with poetry, such form brings harmony, order, and integration to the subject matter.

Photographers and poets also intensify form through a subtractive process. The poet whittles away the stalk of words until only a few are left, excluding all that are extraneous, so that what is important may be seen in a clear and concentrated way. And so it is with photographs. Good photographs are as much about what gets excluded as included in the frame. By excluding extraneous elements, form is rendered visible and powerful as it organizes the essential elements into a whole and completes the illusion of three dimensionality.

But form is not simply about good graphic design or composition. It’s about the soul. We crave form. It speaks to us. It answers to the deepest needs of the human heart.

In his thoughtful book, Beauty in Photography, Robert Adams writes "Why is Form beautiful? Because, I think, it helps us meet our worst fear, the suspicion that life may be chaos and that therefore our suffering is without meaning.”1 To encounter form, to elevate it in artwork, and to pursue it in creativity bring us into contact with a primordial truth; namely, that beneath the chaos and flux, beneath the apparent meaninglessness of so much of daily life, beneath tragedy, mortality, and seemingly senseless suffering is an underlying order to the universe. Form touches the coherence that binds all things together, including tragedy and suffering, and makes of all of it something meaningful.

Form reminds us that there is a place for us in the universe, and while it is not a place of ultimacy or painlessness, it is still a place of hospitality. There’s room for us in the cosmic scheme of things, and we sense that whatever powers weigh down upon us, however terrible and tragic, are not ultimate; we sense, instead, that the powers that uphold us are greater still. Perceiving form reassures us of the ultimate meaningfulness of life, that the world and our lives in it are no cosmic accident. It’s an inoculation against nihilism.

Nihilism, though it goes by many names, is among the greatest threats of modern life. It does not stop at denying meaning. It quickly replaces it with naked power, the cynical denial of all facts, and belligerent egoism.

In the end, form vindicates Dostoevsky’s idiot who announced that "beauty will save the world.”

And photographs, together with the other arts, can also announce this glorious fact.

———————————

1Robert Adams, Beauty in Photography (New York: Aperture Foundation, 1996) , p. 25.

]]>

Three Tomatoes, 2019

In her provocative book, On Beauty and Being Just, Elaine Scarry explores the nature of beauty, aesthetic experiences, and their connection to the moral life. In this lucidly written little work, Scarry notes that when we experience something as beautiful, we impart to it a sense of “aliveness.”

In highlighting aliveness, Scarry is drawing attention to the way that we experience beautiful objects as having or taking on certain lifelike qualities that beckon us into a relationship with them. We experience them as generative realities rather than as static, inert things. Aliveness transforms an it into a thou (Martin Buber). Beautiful things call out to us, make a claim on us, asking us to acknowledge their inherent worth and moral goodness. We answer the call of beautiful things by imbuing them with sanctity and inviolability. Their fragility awaken in us an urge to protect and secure them. Down deep, we sense, even if only intuitively, that the wellbeing of beautiful objects and our own wellbeing are inseparable and mutually entailing.

When we confer aliveness on something, we are welcoming it, extending a kind of hospitality to it, allowing it to take up residence under the roof of our moral regard. This requires what philosopher Iris Murdoch calls “unselfing,” a decentered state of self-forgetfulness.

But something very curious accompanies this unselfing: intense pleasure. In granting aliveness, two things happen in the same moment: we are displaced as the measure of all things as the beautiful object is placed on an elevated moral footing with ourselves; and this in turn awakens in us deep joy and pleasure. But this is counterintuitive. Most of the time we conflate pleasure with a heightened sense of our own power and importance rather than with their diminishment. Beauty exposes this narcissistic lie.

Here is a delightful fusion between the perceiver and perceived object that awakens in us a felt sense of our own essential embeddedness in the vast web of cosmic interdependencies. Freed from ourselves, we can be free for the other in joy and delight. [1]

Granting aliveness to what is beautiful makes possible graced living, a way of life in which the heart enthusiastically assents to and participates in the cosmic "yes" pronounced over the universe.

Beauty and aliveness remind us that the seeds of human fulfillment are not gathered up from the small plot of the lone heart. Rather, we come upon them scattered in the vast tangle of cosmic interdependencies that always also whisper a word of moral obligation.

Aliveness. It's there in three simple tomatoes still possessed of their delicate stems.

----------------

[1] Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and Being Just (Princeton University Press, 1999), esp. pp. 80-114.

]]>

Coast Live Oaks Trees, 2019

To see creatively we must learn to relax our expectations. Only then will we encounter the ordinary on its own terms. When it happens, things become gifts, observation grows into perception, and the ordinary opens onto mystery.

I have hiked and photographed at Montaña de Oro State Park in Los Osos, California for many years without ever seeing this small grove of trees on the side of the road near the park entrance. I have always been too busy looking elsewhere, eager to pass beyond the entrance to go deeper into the park to walk along the magnificent cliffs overlooking the violent surf crashing on the rugged rocks below. That's what this stretch of coastline is known for, and it's what I expect to see.

But on a quiet, cool morning this past January, I happened to see this small grove of trees that was hidden in plain sight. I wasn't looking for it. It surprised me.

I spent an hour among the trees, exploring their beauty.

Gift. Perception. Mystery.

Yet, ordinary.

Mississippi River Botanic Series, No. 14

"We are saved in the end by the things that ignore us."

-Andrew Harvey [1]

Among the things I like to photograph are those that have no apparent human value. I like things that have nothing to do with us, that offer us no advantage and that have not been swept up in the tidal pull of commodification. I like worthless things precisely because they ignore us.

The weeds, vines, and brush along the shoreline of the Mississippi River are among such things. They are a thorny nest of useless things that grow up among the mud, rocks, and driftwood left behind by the receding river.

It takes time and patience to see the beauty of this overgrown tangle. At first, it seems that there is no order, no beauty, only out-of-control weeds, many of which have hostile thorns eager to stab the flesh of trespassers. And then there is the tangle of vines growing over concealed, loose rocks that plot our downfall on the steeply sloped river bank. But even imputing such motives to useless things is one last gesture of the self-centeredness from which we are about to be delivered.

As we slow down and cease grasping for large gestures of beauty, the small ones emerge. Here and there in the relentless chaos, is a little bit of order — a small cluster of seed pods caught poetically in the vines, performing in rhyme. But we will miss it if we are anxious "to see something." Only when we give up the search will it find us.

The beauty of useless things is often this way. It is given from beyond ourselves. To experience such beauty is to sense some plasticity of self. The rigid borders of the self, guarded by anxiety, cognitive control, and egoism, become fluid and permeable in the presence of such little surprises. When this happens, we glimpse a fleeting but deep truth, the fact that in the end our lives are not our own, and they are framed by purposes and mysteries much larger than us. The beauty of useless things dethrones us, reminds us that we are not the measure of all things. We are among the measured. And it is freeing.

Here in the economy of useless things lies a new self.

---------------------------------

[1] Andrew Harvey, A Journey in Ladakh (New York: Houghton Mifflin, 1983), 93. Quoted in Belden Lane, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Desert and Mountain Spirituality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 57.

]]>

After the Miracles are Gone, 2017

"Do we know what it means to be struck by grace? It does not mean that we suddenly believe that God exists, or that Jesus is the Saviour, or that the Bible contains the truth…. Furthermore, graces does not mean simply that we are making progress in our moral self-control, in our fight against special faults…. [Grace] strikes us when, year after year, the longed-for perfection of life does not appear, when the old compulsions reign within us as they have for decades, when despair destroys all joy and courage. Sometimes at that moment a wave of light breaks into our darkness, and it is as though a voice were saying: ‘You are accepted. You are accepted, accepted by that which is greater than you, and the name of which you do not know. Do not ask for the name now; perhaps you will find it later. Do not try to do anything now; perhaps later you will do much. Do not seek for anything; do not perform anything; do not intend anything. Simply accept the fact that you are accepted!’ If that happens to us, we experience grace. After such an experience we may not be better than before, and we may not believe more than before. But everything is transformed...."

-Paul Tillich[1]

"The blues…is an impulse to keep the painful details and episodes of a brutal experience alive in one’s aching consciousness, to finger its jagged grain, and to transcend it, not by the consolation of philosophy but by squeezing from it a near-tragic, near-comic lyricism.”

-Ralph Ellison[2]

In the Gospels, we find many stories in which Jesus healed people. A woman follows quietly behind him and touches the hem of his garment and is healed instantly. Four good, strong friends lower a man through the roof of a building to interrupt Jesus so he will heal their friend, and Jesus does it. In Jericho, a blind panhandler named Bartimaeus, despite being sternly ordered by the authorities to be quiet, yells out to Jesus as he passes by, “Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me!” And Jesus heals him. The healing stories are surely dramatic. Who doesn’t love a good old-fashioned miracle story?

But when I am honest, I must admit that these stories leave me with as many questions as answers. What about all those other people in the crowd just as much in need of healing as the woman but who couldn’t get close enough quickly enough to touch Jesus’ garment because he was moving too quickly or the crowds were too thick? What about all those other broken people who don’t have four good, strong friends willing to dismantle a roof to get them healed? What about all those other quiet panhandlers in Jericho in need of healing whose voices were drowned out by the one loud mouth who stole the show? For every individual fortunate enough to be healed miraculously by Jesus, there are throngs of people just as much in need of healing that he never heals, at least not miraculously and dramatically.

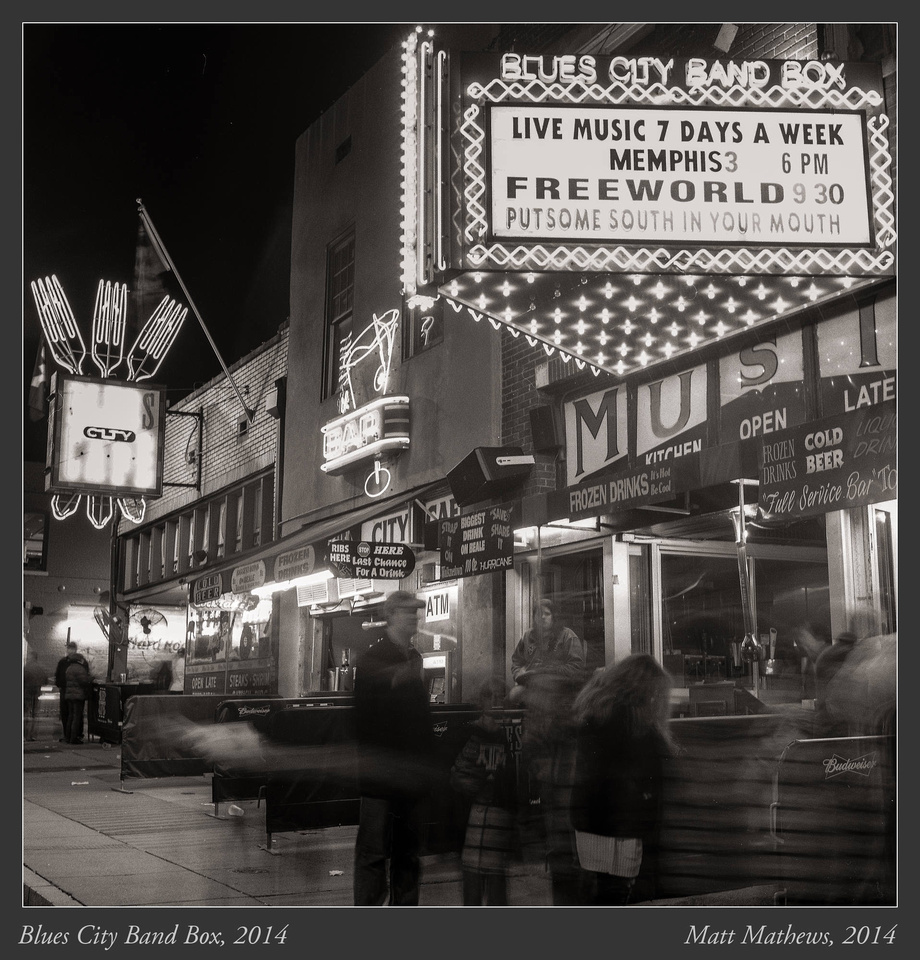

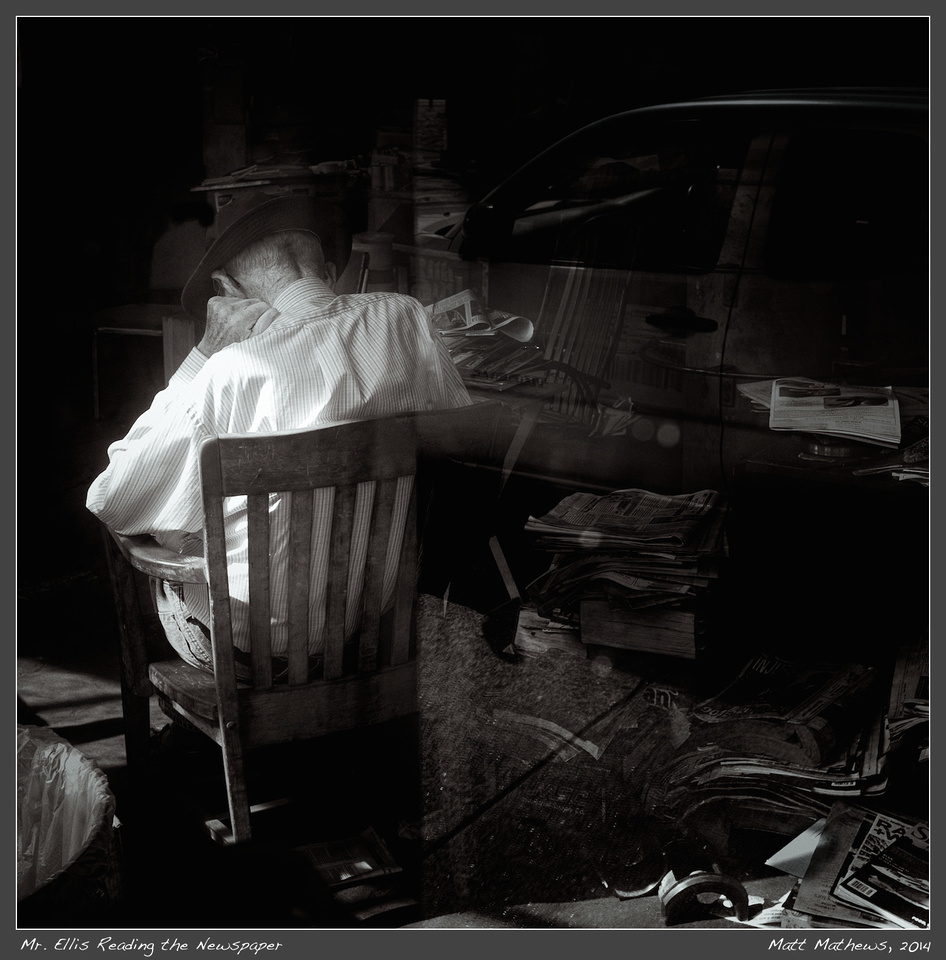

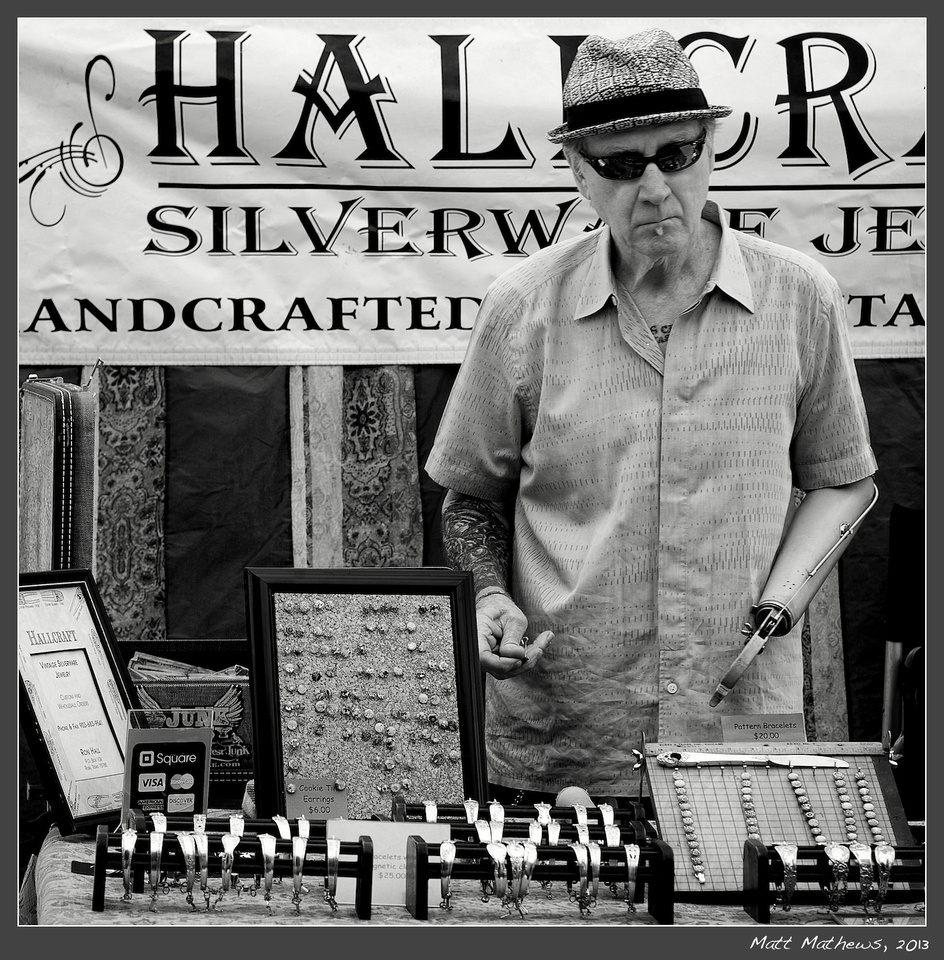

Where do these folks go to get healed? Some go to church, I suppose. Others go to Blues festivals, at least that’s now what I believe after photographing the Juke Joint Festival in Clarksdale, Mississippi for several years. Clarksdale and the Blues are for broken and flawed people, suffering people who, for whatever reason, can’t seem to get healed instantly, dramatically, and miraculously by Jesus in the usual places.

Whatever the seat of our particular suffering, when the Blues are performed, we run our fingers over the jagged edges of our brokenness, our inadequacies, our suffering. We feel the sharp-edged pain of our failure to get skinnier, smarter, wealthier, healthier, younger, prettier, or holier. We confront the loss of failed relationships and the host of other moral inadequacies and untamed compulsions that still reign in us. And we touch the hopelessness and despair awakened by a world hellbent on violence and injustice. The Blues give voice to this tragic reality, this tangle of finitude and brokenness that is inescapable in all human life. In this regard, the Blues are more honest than what often happens in church. The Blues are a much messier form of healing than miracles, and perhaps that’s why they persist long after the miracles are gone.

But the Blues do more than give voice to the brokenness in our lives. They enable us to transcend it, to squeeze from it some inexplicable, ineffable triumph. Let's call it grace. No, let's be bold. Let's call it Gospel, "good news" that blesses Luke's "poor" and Matthew's "poor in spirit." By singing about suffering, the Blues ultimately beat it, well, kind of. They beat it, albeit in an oblique way, with humor, pathos, and permission to embrace our bodies and spirits as they are. They beat it by unshackling bodily and spiritual desires, emotional longing, and the satisfaction of all of these from the shame and violence of false moralism and the politics of domination.

The Blues knit wounded selves back together again. They do so not by extricating us from the cruelties of life. That would be too easy; that would be cheap grace and bad music. The Blues are cruciform grace; they make power present through weakness. In them, we find divine grace incarnate in human suffering well after the miracles are gone.

It is foolish, of course, to say that everything sung in the Blues is Gospel; surely the Blues too are fragile and susceptible to the very tragic misdirections and distortions that they themselves identify. To say this is simply to recognize that old truth that not every word the preacher utters is Gospel; and yet sometimes the preacher's clumsy or even self-serving words become Gospel through the power of Another. So it is with the Blues.

[1] Paul Tillich, “You Are Accepted,” The Shaking of the Foundations (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1948); pp. 161-2.

[2] Ralph Ellison, "Richard Wright's Blues," in Shadow and Act (New York: Quality Paperback Book Club, 1994 (1964)); p. 78. Quoted in James Cone, The Cross and the Lynching Tree (New York: Orbis Books, 2013); p. 16.

The Jewish Boy, 2017

"The face opens the primordial discourse whose first word is obligation."

*****

"The Other faces me and puts me in question and obliges me."

*****

"The face resists possession, resists my powers.... The face speaks

to me and thereby invites me to a relation..."

*****

"The face is what forbids us to kill."

-Emmanuel Levinas [1]

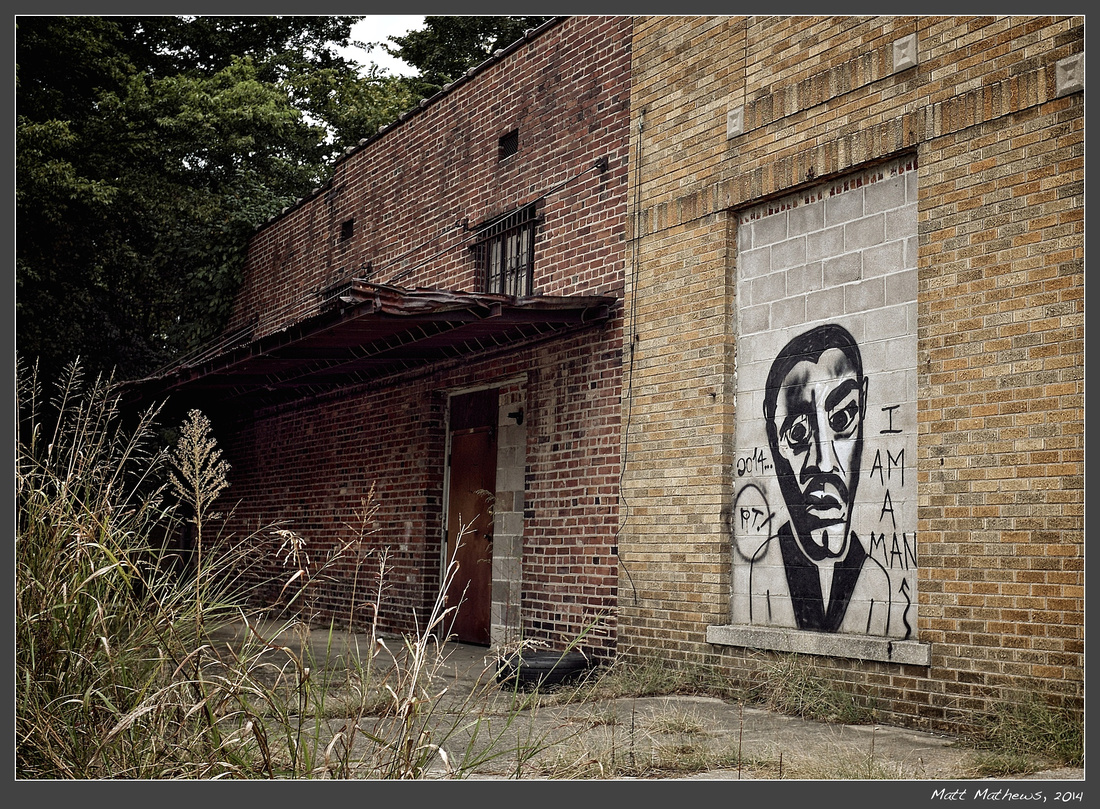

In the fourth chapter of Night, Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel recounts a scene from his time in a Nazi concentration camp that few readers can ever forget. Wiesel describes the public hanging of a young Jewish boy accused by the Nazis of sabotage. Public hangings by the Nazis were not uncommon in the camps as part of the comprehensive strategy of terror. But never had the Nazi guards publicly hung a young boy. When describing the boy, Wiesel notes that he "had a delicate and beautiful face -- an incredible sight in this camp." As the boy dropped from the gallows, it became clear that his little body did not have sufficient weight to snap his neck, ensuring a quick death. Instead, his body twisted and writhed as he slowly suffocated to death. As his delicate body dangled in sky, Wiesel notes that a change came over the otherwise hardened prisoners. For the first time, they came face to face with the profound sense of the absence of God. What kind of a God allows delicate-faced little boys to be tortured to death as public spectacle? For Wiesel there was no easy theological answer, just an overwhelming sense of divine abandonment in the presence of irredeemable evil. Like the prophet Jeremiah, all Wiesel could do was shake his fist at God, crying out in anger and protest, demanding that God be God. [2]

As I was walking in the Jewish neighborhood of Antwerp, Belgium recently I decided to sit and rest near a busy intersection. It was morning, and the Hasidic parents were escorting their children to school on their way to work. As Jewish men gathered to cross the street, a little Jewish boy with "a delicate and beautiful face" turned around to watch me as I began to photograph him. His gaze met mine.

I do not know the boy's name. I do not know his age. I know nothing about him, save one thing. I know his face, framed as it is by his strange shylocks. His posture and position next to the grown men, themselves strangely attired, accentuate the smallness, fragility, and awkwardness already carried in his gaze. His might just as easily have been the face of that other Jewish boy twisting on the end of a Nazi rope.

In the end, it was the gaze of his "delicate and beautiful face" that stopped me in my tracks. This was no mere photo op. Here was a disruption, a call to something deeper than a snapshot stolen on the run. Here was a brief but powerful call to connection, empathy, and even moral and spiritual transformation.

Jewish philosopher Emmanuel Levinas helps us make sense out of our encounters with the gazing faces of such strange and foreign others by seeing in them both a disruption and a summons.

Here was a disruption of my common ways of seeing the world that assume that it and others must conform to my expectations and norms if they are to be worthy of my moral regard. Here in the face of this particular Other was resistance to my desire for sameness that anonymizes and invisibilizes individuals, thus blunting my sense of empathy with and moral obligation toward them. Here too was a summons out of inauthenticate selfhood, rooted in anxiety and control. Here was a summons into an intersubjective world rich with empathy, moral obligation, and affective regard for the wellbeing of a strange and foreign Other. In his face, I found an invitation out of the habits of my false and hegemonic self that tempt me to look away to avoid his gaze, thereby short-circuiting the emergence of empathy, connectedness, and spiritual transformation that meeting his gaze might occasion.

It is difficult for us to grasp the depth of evil that produces genocides. We are sometimes tempted to explain such evil by appealing to supernatural origins and the idiosyncrasies of individual personalities. Only demons and devils could twist a person into a Hitler, we say; thus tacitly reassuring ourselves that he is a monster thoroughly unlike the rest of us. Other times, we chalk Hitler up to mental illness, his evil the product of an atypical psychopathic personality; again tacitly reassuring ourselves that he is an exception, an anomaly. Such explanations are false because they eclipse the social forces and broader cultural dynamics that produce such so-called "madmen."

The danger of such "explanations" is that they prevent us from engaging in more self-critical analysis. When Hitler and Holocausts are presented as suddenly storming unannounced onto the stage of history, it discourages us from asking the deeper questions of who built the stage on which they appeared. The truth is that that the grounds for such evil must be first be cultivated over time in society, a complex process that ultimately enlists all of us as accomplices eager to look away from the face and gaze of those strange and foreign others in our midst who seem to threaten us. Evil leaders are to a significant extent the byproduct of the societies that produce them.

When I view The Jewish Boy, I see the "delicate and beautiful face" of not one but two Jewish boys, the first on an Antwerp street corner, the second twisting on the end of a Nazi rope. My hope is that this photograph prompts viewers to place themselves purposefully among the outsiders, to look into their eyes, to be drawn out of themselves into communion with those who are foreign and strange. Only when we meet the gaze of such particular faces can we encounter their, and ultimately our own, fullest humanity.

As I linger still awhile longer over this photograph, I catch a glimpse of yet another Jewish boy, but one whose name I know. He wandered in the temple, lost, vulnerable, and probably afraid while his parents searched frantically for him as they backtracked toward Jerusalem. His parents found him, of course, but only after the teachers met his gaze, greeted him, and discovered in his face the possibility of the healing of the nations. [3]

-------------------

1. Emmanuel Levinas, Totality and Infinity: An Essay on Exteriority (Trans. Alphonso Lingis. Duquesne Press, 1969), 201, 207, 197, 198; Ethics and Infinity (Trans Richard A Cohen, Dusquesne Press, 1964), 86. I am indebted to Bruce Young who identified these and other quotations that synopsize key elements of Levinas's philosophy. See http://english.byu.edu/faculty/youngb/levinas/face.pdf.

2. Elie Wiesel, Night. (Trans. Marion Wiesel. Hill and Wang, 2006)

3. For the account of Jesus in the Temple, see Luke 2:42-52.

]]>

Razor Wire and Broken Fence behind the Happy Mexican Restaurant, 2017

Two fish were swimming side by side in the ocean. The first said to the second, "the water is warm and clear today." The second responded, "what water?" [1]

Attentiveness does not just happen. It must be cultivated. We can only be awakened to deeper seeing, and ultimately to deeper living, if we teach ourselves to pay attention.

The men and women who began moving to the deserts of Egypt and Syria in the third and fourth centuries to practice a contemplative desert spirituality knew this. Theirs was a world in which faithful living had become difficult. It was made difficult by the emergence of an empire which often cloaked its quest for military conquest, economic domination, and exploitation of the vulnerable in Christian symbols and rhetoric. Beginning with Constantine in the early fourth century and extending down through the history of "Christendom" to our own time, the Prince of Peace has often been gradually transformed into a triumphalist, flag-waving Jesus who sanctifies the imperial bid for domination, exploitation, and the suppression of difference in the name of security and patriotism. In a fateful dream on the night before his greatest battle at the Milvian Bridge, Constantine saw the Chi-Rho and heard the words, "in this sign, conquer." His dream seems to be a common one.

The driving question for these desert contemplatives was simple but profound, how do we live faithfully in a world where the faith we profess has been co-opted by empire? It was a subversive, unpatriotic, unwelcome question, and it remains so in this, our own season of empire.

The desert contemplatives answered this question by withdrawing from the world to live in the desert. While they withdrew from empire, they did not abandon the struggle against it. They knew that the line between our inner and outer landscapes is porous. They withdrew from the outward world of empire so that they could focus on the ways that empire comes to occupy the inner world of the soul. These desert monks knew that the political, military, and economic engine of empire was fueled by that other, more pernicious and elusive form of empire that colonizes the heart, enslaves the imagination, and infects all the small and ordinary activities of daily life in ways that often remain invisible to us.

At the heart of their strategy of resistance, lay spiritual practices such as prayer, meditation, worship, fasting, extending hospitality to vulnerable guests, engaging in mutual correction, gardening, basket weaving, and caring for the sick, exploited, and outcasts of empire. They knew that we cannot merely profess a counter-cultural spirituality; we must train for it daily by reimagining even the most mundane of daily practices, freeing them from the dynamics of violence, domination, and exclusion pursued in Jesus' name. Such practices exorcized the demons of empire that dwelt in the heart and that keep empire alive in the outer world of politics, economics, and culture. The conflict with empire was indeed a cosmic conflict with "the powers and principalities of this present age," but victory would come only by prevailing in the small skirmishes of ordinary daily life. Victory would come by changing one's diet, clothing, sleeping practices, labor, and social circles. [2]

The spiritual disciplines aimed at many things, but among the most important of them was the cultivation of prosoche, attentiveness. Attentiveness is mindful seeing, purposefully lingering before things so that they may reveal themselves on their own terms and in their fullest depth and complexity. Pursuing prosoche meant learning to see the world as it really is rather than through the distorting lens of anxiety and acquisitiveness brought to it by the false, fallen self. Practicing prosoche meant observing carefully, deliberately, and dispassionately the subtleties of things as they really are. Such attentiveness awakened a heightened sense of nuance, a new-found comfort with complexity and ambiguity, and joyful delight in the variegated beauty of ordinary, mundane things. To practice prosoche was to retrain our eyes to see the world as God would have us see it, undistorted by the possessiveness and drive for domination rooted in the false self of empire. Pursuing prosoche was an antidote to illusion, a celebration of the realness of things as they are in their naked givenness and stark facticity. To engage in prosoche was to shatter the delusion of "alternative facts" and the spin of internalized imperial narratives of fear, threat, and conquest. Cultivating prosoche meant deepening one's capacity for complexity, making room for the foreignness of things and other people. [3]

Prosoche was closely related to diakrisis, that form of wise, patient discernment that makes nuanced, measured judgments informed by carefully seen, subtle, relevant distinctions. [4] Together Prosoche and diakrisis undermined the reductionistic, binary oppositional thinking demanded by imperial propaganda and the politics of fear and exclusion. Prosoche and diakrisis were an inoculation against the self-serving oversimplifications produced and required by our anxious, imperious drive for domination and control. To recast things in more contemporary terms, attentiveness and discernment destabilize "either-or," "yes-no," "us-them," "black-white," "insider- outsider," "liberal-conservative," and "deserving-undeserving," for example. By so doing, they school the imagination in resistance to the reductionistic thinking demanded by empire.

Simplistic binary oppositional thinking and living have again become a mark of our age. They are fed by political memes on social media, pithy bumper stickers, "news" networks that pluck only partisan soundbytes from complex stories, political propaganda, and extremist blogs masquerading as reliable sources of news. They are also fed by the fundamentalist religion of the right, and, if we are honest, of the left as well. Such thinking thrives on fear and anxiety, promising us a seemingly irresistible form of clarity and certitude about the dangerous world before us. Such thinking seems to bring a reassuring order to the swirling chaos of our troubled world.

But if the ancient desert contemplatives can teach us anything, it is that such simplistic thinking is driven by that old, false self within us, that self that would be its own god. And perhaps we can learn from them to cultivate prosoche and diakrisis again. We cannot, of course, simply mimic their ancient spiritual disciplines in some desperate flight of nostalgia. We will need to adapt them in ways suitable for our own time. Part of such adaptation will mean that we consider again the power of art and artistic creativity in our daily lives.

I have walked behind the Happy Mexican Restaurant in a struggling section of downtown Memphis many times. Its façade is painted in bright colors and bears kitschy images of stereotyped mariachi singers whose dark, gap-toothed faces grin without pause. But behind the Happy Mexican, smiling faces give way to a tall fence, a tangled weave of metal, broken wood, and razor wire designed to keep thieves and vandals out. Behind the fence are dumpsters filled with the rotting food scraped from last night's plates. Next to these is a large grease trap that holds the discarded, acrid oils from the kitchen fryer. It stinks behind the Happy Mexican, and it is surely an ugly place.

And yet, as I stood next to the fence for a twenty minutes studying the shapes and patterns, I was struck by the graceful curves of the razor wire designed to tear flesh. The pattern of the fractured wood lattice behind it only multiplied the strange beauty of geometry set against the sunless grey sky. Here in ugliness was beauty. But this beauty did not erase ugliness. The fence was ugly and beautiful at the same time, a soiled, secular sacrament suspended in the sky. My eye said both "yes" and "no," and the longer I looked the more richly commingled they became. Here was a moment of prosoche, that deep attentiveness to the complexity of the world that awakens diakrisis, discerning judgment at home with ambiguity, complexity, and even paradox. The givenness of this little, smelly scene disrupted the simplistic impulse to add it quickly to the column of ugly things and rush on in search of something pretty to balance the imperial ledger.

I do not think a single encounter such as the one behind the Happy Mexican will expunge empire from the mind. But perhaps as the desert contemplatives thought, cultivating such encounters in the small, daily skirmishes of ordinary life will eventually help us do so. At any rate, that evening as I watched the news, lying presidents, spying microwave ovens, make-believe wiretaps, chest-thumping patriotism, inept propaganda, and the political memes of social media seemed just a bit farther away.

Maybe a fish was becoming aware of the water.

-------------------------------------------------------------

- Borrowed and paraphrased from David Foster Wallace, "This is Water." Commencement Address at Kenyon College, May 21, 2005. Transcript available at https://web.ics.purdue.edu/~drkelly/DFWKenyonAddress2005.pdf

- For a general introduction to the rise of ascetic, contemplative desert spirituality in late antiquity, see Derwas James Chitty's, The Desert a City: An Introduction to the Study of Egyptian and Palestian Monasticism Under the Christian Empire (St. Vladimirs Press, 1977). For a more focused treatment of the emergence and role that the desert contemplatives played in the context of empire and its complex patronage system, see Peter Brown's classic essay, "The Rise and Function of the Holy Man in Late Antiquity" (The Journal of Roman Studies, Vol. 61 (1971), pp. 80-101). Brown's essay is available online at https://faculty.washington.edu/brownj9/LifeoftheProphet/The%20Rise%20of%20the%20Holy%20Man%20-%20Brown.pdf

- Douglas E. Christie, The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013. See especially chapter 5, "Prosoche: The Art of Attention," pp. 141-78.

- Christie, 148

]]>

Boulders in the Surf, No. 2

Every summer when I was a boy, my parents would take us on vacation to Santa Cruz, California. For a household of boys, there was no place better on earth than Santa Cruz. We divided our time between three great attractions, the pier from which we fished, the beach where we swam and built sand castles, and the boardwalk where we indulged the world of carnival and theme park. The boardwalk was for evenings, and we filled them with rides on the Big Dipper, the Mighty Mouse, and the Log Jam. When we weren't riding the rides, we played games, and most importantly for me, created "spin art."

Nourished on the ambrosia of cotton candy and caramel apples, we made our way to the south end of the boardwalk, to the spin art booth. And here, like the Creator hovering over the primordial darkness and void, we hovered over a chaotic, paint-stained counter eager to create. At each station was a machine to which the operator attached a piece of blank rectangular art paper than spun around so fast it became a blurred circle. Here was our canvas, and there was no need for paintbrushes. Instead, for ten frenzied minutes we squirted streams of paint from plastic bottles onto the spinning paper. We learned to squeeze softer and harder. We learned how to press an awl gently against the spinning paper to inscribe texture and blend the paints.

And when we finished, and only when we finished, the operator would stop the motor that spun the paper. And then for the first time, we would behold the finished artwork sitting still before us. It was our moment of revelation. Then the orange-aproned operator, like a priest reverently raising the Host, would delicately lift your masterpiece from the machine and set it aside to dry before you returned to collect it. Nourished and tired, we proud Picasos toted our artwork back to the Salt Air Court where we transformed our little white motel room into a gallery.

I got hooked on spin art. Perhaps it was largely because I was not yet old enough or tall enough for many of the gut-jumbling rides enjoyed by my older brothers. But there was another reason, the thrill of waiting and not knowing, the thrill of the big surprise at the end. For those ten minutes of squeezing paint on spinning paper, my creative intentions and gestures were taken up by wild centrifugal forces beyond my control to produce something that was at once mine and not mine. All my technique and craft, in the end, were gathered up by the machine and spun wildly into something over which I ultimately had no control. Spin art happened in the unpredictable space between artistic intention and technique, on the one hand, and chance and cosmic forces, on the other. Here was theme park eschatology -- a boy living by artistic faith, confident that beauty would emerge from the tension-filled space between paint applied and paint drying.

It has been over thirty five years since I have made a piece of spin art on the breezy boardwalk by the sea. But just a few weeks ago, I stumbled into it again. Well, sort of. This time it involved no paper, paint, or spinning machine. With camera in tow, I descended the dunes to an isolated stretch of untamed beach along the Pacific coast in California. The beach was scattered with boulders large and small. As the waves of high tide crashed mightily, they tossed the boulders into one another, creating an eerie thunder on a foggy morning.

I chose to make long photographic exposures, slowly recording the water as it rolled unpredictably over and around the boulders. Once opened, the shutter remained open for many seconds, and what happened during that time was beyond my control. I could anticipate when waves might crash and where water might flow and trip the shutter accordingly, but in the end what happened in those seconds was always unpredictable, surprising, and beyond my control. Sometimes the water foamed unexpectedly as it took its uncharted path around the rocks before beginning its streaky return to the sea. Sometimes incoming waves collided with returning waves and produced watery volcanoes of churning sand. For those seconds when the shutter was open, the water went where it wanted, when it wanted, in the ways in wanted, and how the camera would record this was equally a mystery. All I could do was trip the shutter, wait, hope, anticipate.

Here was spin art of a higher order.

Here was a middle-aged man reborn a boy by the briny baptism of the sea.

Here again was the eschatology of creativity, suspending my awareness between present intention and future outcome, between purposeful technique and cosmic surprise.

Here again was the undiluted wonder, potent mystery, and unfettered delight that too often only mystics and children know. And maybe messiahs.

"Let the little children come to me," he said. [1]

-------------------------------------

1. Matthew 19.14. New Revised Standard translation.

]]>

Boulders in the Surf, 2017

I cannot photograph sound.

And yet, twice in the past year I have desired to do so. In January of last year, following a snow storm in the Sierra Nevadas, I journeyed up to Yosemite to photograph. I began my circuit of the Valley with a stop at Bridal Veil Falls. The footpath to the base of the falls was covered in several inches of treacherous ice. Most of the few visitors in the park who bothered to stop chose to forego the walk and view the falls from the safety of the parking lot. As I gingerly worked my way up to the base of the falls, I heard peals of thunder overhead. But the skies were blue. It was not thunder. It was the sound of large sheets of ice high above the falls cracking, breaking loose, and smashing against rocks on their way over the cataract. This strange, thunderous sound echoed sharply over the whole of Yosemite Valley.

And just a few mornings ago, I stood atop a rocky shelf along an isolated stretch of untamed Pacific coastline at Montaña de Oro State Park. It was a foggy morning, and again I heard the sound of thunder that was not thunder. It was the sound of large, submerged boulders on the shoreline being lifted and tossed violently against one another by the fierce waves of high tide.

There is something unsettling and eerily fascinating about this thunder of ice, rocks, and water. Immanuel Kant and the Romantic thinkers and artists of the nineteenth century would likely have categorized these encounters as experiences of the sublime. The sublime, they insisted, is different from the beautiful. The beautiful refers to things on a human scale -- small, delicate, pretty, and manageable by the mind. Experiences of beauty evoke an immediate sense of satisfaction and unalloyed pleasure as one perceived the presence of symmetry, form, and balance. Beauty awakens a sense of being at-home in the world. Beauty consoles, comforts, and reassures. The mind is up to the task of beauty.

Experiences of the sublime are different, insisted Kant and the Romantics. We experience the sublime when we are confronted and overwhelmed by the vast, unbounded, primal forces of the universe. When we experience the sublime, we are radically disoriented. We feel swallowed up by the vastness of cosmic forces and sense acutely our smallness and vulnerability in the grand scheme of things. For Kant, it was the vastness of "the starry sky above" that evoked a sense of the sublime. The power of ocean tides and echoing peals of thunder have the same effect. These experiences of boundlessness, displace and dislocate us, disrupting our cognitive powers. When they do, they evoke something other than a simple, direct sense of pleasure and at-homeness in the world. Instead, they pull us affectively in multiple, contrary directions all at once. [1]

Rudolf Otto, while writing about "the holy," might just as easily have been writing about the sublime. Otto characterized a holy object as a mysterium tremendum et fascinans. [2] Holy things are mysterious, "wholly other" things that confound the mind and evoke a sense of fear and fascination at the same time. We are drawn irresistibly across treacherous terrain to the cracking ice and jumbling boulders even as we pull back with caution and fear at their danger and disregard for us. The thunder of rocks, water, and ice calls out to us to come closer for a better look even as we know that with one misstep these elemental forces can kill us. To feel these countervailing impulses at once is a mark of the sublime.

This distinction between the beautiful and the sublime is not without its problems. Repeating the gender essentialism of patriarchy, for example, nineteenth-century thinkers identified beauty with the feminine and the sublime with the masculine. And while it was not their intention to diminish the significance of the beautiful in the interest of the sublime, such was often the effect in practice when the distinction became gendered. Patriarchy demands beautiful but subordinate women rather than sublime ones. The former please and serve men, while the latter threaten to undo them. [3]

And yet, despite the problematic overlay of patriarchy and gender essentialism, one senses an authentic insight here into some kinds of aesthetically charged experiences. Tangled and muddled by gender politics as this distinction is, we do, in fact, have these experiences of the sublime, and they are different from other experiences of beautiful things.

Such experiences of the sublime are powerfully formative. They shake us awake from the slumber of our grasping egocentrism. We discover that we are not the center, force, and fulcrum of the universe. We sense our smallness and vulnerability again, and paradoxically it is liberating. They free us from the compulsive drive to control reality, from the fear that drives us into the arms of false messiahs who promise to make us great again.

I cannot photograph the thunder of water, rock, and ice, and that fact is a palpable reminder that I am not the measure or even measurer of all things. But perhaps a photograph such as Boulders in the Surf can crudely and clumsily bear witness, even if only obliquely, to the sublime, to the fact that "we are saved in the end by the things that ignore us." [4]

-----------------------------------------

1. For a brief overview of the distinction between the beautiful and sublime in Kant and Romanticism, see Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and Being Just (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 82-6.

2. Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy. Trans. John W. Harvey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1923; 2nd ed., 1950 [Das Heilige, 1917].

3. For a more comprehensive critique of the distinction between beauty and the sublime, see Scarry, On Beauty, 82-6.

4. Anthony de Mello, One Minute Wisdom. Quoted in Belden Lane, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Desert and Mountain Spirituality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 57.

]]>

Train Cars, Rudyard, Mississippi, 2016

Ours is an age that has come to think of beauty and art as luxuries easily done without rather than as necessities required for living well.

Our willingness to dispense with them is written into much modern home construction and neighborhood development, for example, where our fetish for more and cheaper square footage and uniform design eclipses attention to the flow and arrangement of space, the presence or absence of natural light, and the unique, artful character imparted to a living space by careful attention to detail and variety. This impulse to dispense with beauty and art is also present in our educational institutions, where art programs are the first ones cut when budgets must be trimmed. The kids can do without paint, clay, and crayons, but they can't do without math and science, standardized tests, and computer skills, or so says the unimaginative "wisdom" of our age.

And on the few occasions when we finally turn in the direction of beauty, we easily get distracted by the pretty, by ornaments and decorations that lack depth or complexity. We want art that matches the couch rather than touches the soul. We confuse beauty with decor.

What exactly is lost when we slowly drift away from beauty and art?

Answering this question requires that we ask a more basic one, what makes a thing beautiful? Across the western intellectual tradition, the answers to this question has been complex and varied. But there is one aspect of the answers that recurs in nearly every age; and that is form. Form refers to the organizing principle of a thing, the integrative aspect that binds its parts into a harmonious whole. Form imparts orderly arrangement, coherence, and structure to an entity. A natural or artistic entity is beautiful when its various aspects are organized, integrated, and patterned harmoniously. Form expresses itself as the arrangement and order within a thing that make it a unified whole, something greater than the mere sum of its parts. Form sometimes goes by its Christian name, Logos, or by its Jewish name, Wisdom.

Form is what differentiates music from noise. If I drop my kitchen pots and pans on the floor, they will strike many of the same notes as the organist playing Beethoven's "Ode to Joy." But why is this noise rather than music? It is noise because the notes are not well ordered and harmoniously arranged. They lack proportion and symmetry, structure and coherence, integration and unity. The difference between "Ode to Joy" and clanging cookware is that the former has superior form while the latter lacks it almost entirely.

When we experience the form revealed in beauty, we feel down deep in our gut that the world in which we live is governed by order rather than chance, purpose rather than accident, pattern rather than chaos. In the presence of beauty, we sense deeply that our lives and the existence of all other things fit together in some coherent way that is ultimately meaningful. The experience of beauty awakens and intensifies that felt sense that the universal power that generates and integrates our lives is greater than the powers that seek to pull them apart. We are assured affectively that the universe is shot through with meaning, that its primal force is an integrative love, and that life is well lived when it consents to the harmony that binds all things together and yokes them to their transcendent purpose. Our native response to perceiving form in beautiful things centers in delight and joy that reorder the heart's deepest desires, drawing us out of ourselves toward the other in exuberant, spontaneous love.

To experience the form present in beauty is to hear a transcendent Witness declare that the world is good; that it is as it ought to be, and that there is room for us in it. The form of beauty awakens in us a sense of wellbeing, an intuitive, sure sense that the universe is not fundamentally hostile to our existence despite the reality of suffering in our lives. Beauty reveals the joyful truth that my life is never wholly my own own, that power and pose cannot ultimately trump goodness and truth. Form revealed in beauty exposes the lie that the only meaning my life has is whatever arbitrary meaning I or society assign it. The form manifested in beauty awakens hope, a sense of possibility, and a sense that life, love, and justice ultimately matter. Beauty thus gives birth to our moral imagination and awakens moral motivation.

In the end, the real danger of a beautyless, artless world is not so much ugliness but nihilism, the loss of that existential meaning that is bedrock to our humanity.

]]>

California Sea Otters, Mother and Pup, 2016

When I was a boy, I raised pigeons. I enjoyed releasing them many miles from home and finding that they had returned to the coop. On very rare occasions when two steel-grey homing pigeons mated, the plumage of their offspring was not at all like that of the parents. The parents had "thrown a pie" as pigeon-keepers called it. The plumage of the offspring was mottled, dappled in odd colors, and uniquely its own -- the wild resurgence of recessive genes. -MTM

|

Pied Beauty Glory be to God for dappled things-- For skies of couple-color as a brindled cow; For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim; Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches' wings; Landscape plotted and pieced--fold, fallow, and plough; And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange; Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?) With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim; He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise him.*

-Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1877 |

------------------------------

*This poem is in the public domain.

]]>

Toadstool and Pine Needles, 2013

In My First Summer in the Sierra (1911), John Muir offers the following account of sketching a sugar pine tree in the Sierra Nevada.

| I never weary of gazing at its grand tasseled cones, it's perfectly round bole one hundred feet or more without a limb, the fine a purplish color of its bark, and its magnificent outsweeping, down-curving feathery arms forming a crown always bold and striking an exhilarating... At the age of fifty to one hundred years it begins to acquire individuality, so that no two are alike in their prime or old age. Every tree calls for special admiration. I have been making many sketches, and regret that I cannot draw every needle. [1] |

In the midst of a creative act, Muir discovered that "no two [trees] are alike." So intense is his insight that he longs to sketch each and every pine needle because one cannot substitute for another without loss. Muir was smitten by the power of particularity.

Artmaking opens up this power of particularity in our lives, evoking a deeply felt sense of the irreducible uniqueness of the single thing in front of us right now. Under its spell, we linger over the minutest detail, offering it a long, loving, sensuous gaze. As we do, everything else fades temporarily from view. It is as though time stops and we are wholly absorbed in the intricacy of this and only this thing. We come to know it immediately, intimately, and vividly. We lose ourselves in it only to find ourselves again, but now we are richer for having been woven together intimately with the object and the felt mystery it makes present.

As we sketch, photograph, or paint the pine needle, we are so keenly focused on its particularity that the boundaries between subject and object dissolve. The anxiously patrolled borders of the self become porous, fluid, and elastic. The self relinquishes its drive to control -- physically, emotionally, and cognitively. The ego discovers itself open, receptive, and vulnerable. Curiosity dissolves control, empathy replaces hostility, love banishes indifference. Before the pine needle and the felt sense of mystery that envelops it, delight, wonder, and hospitality crowd out fear, hatred, or violence. The self makes room for the pine needle and allows it to be what it is, fragile, beautiful, vulnerable. And now loved.

This kind of artistic awareness is very much like the mystical awareness treasured by the contemplative traditions in nearly all of the great religions of the world. These are not experiences of flight from the world, from the ordinary, from the particular. Rather, they are experiences of a radically new way of being present to the world, to the ordinary, to the particular. When we linger over the beautiful thing, suddenly we and it are cradled in the arms of the Whole, the mysterious Whither and Whence of all being. We have celebrated Communion.

There is a deep paradox here, and it is this. When we severely restrict the scope of our attention to a single being, giving it our total attention and devotion, it becomes a portal onto the Whole. In seeing the one, we awaken to the All. Only by restricting our awareness does it become expansive and capacious. If it is Logos we find, it is always first incarnated.

This graced form of awareness is not the exclusive possession of professional artists or the mystical virtuosi. It is available to all of us, but we must cultivate it. Among the ways we do so is by exercising creativity, by making art. Many of us gave up artmaking when we grew up, shamed out of it by the demands of adulthood and "serious" living. But creativity and art-making are deeply spiritual, transformative practices, capable of renovating our imaginations and reorienting our total affective and cognitive posture toward life over time. When we neglect them in our adult lives, we do so at our own peril.

But what do pine needles have to do with politics? At this moment in American political life, we are a deeply divided people. Beneath our political, cultural turmoil is a deeper spiritual turmoil. We are a people governed by fear, alienation, and isolation. Our fractious politics and lack of empathetic connection to one another are a symptom of our traumatized souls. We are closed off from one another and from ourselves -- angry, alienated, and desperately in search of political messiahs from any end of the political spectrum who we hope will magically rescue us from our problems. But down deep we know that no politician, party, platform, or election will do for our souls what needs doing.

What is required is work rather than magic, and it is work that we the people rather than a single political messiah must do. It's local, particular, grassroots work. It's slow, hard, and risky work. And, as silly and naive as it may sound, I believe that some of this work must be the joyful work of making art. We need to discover or rediscover the bliss of creativity. We need to sketch, photograph, and paint that pine needle right there, right now. We need to do this creative work so that we might discover the transformative power of particularity. Attending deeply to this pine needle, the one right there in front of us now, is one way of practicing ourselves into openness and receptivity to the distinctive colors, qualities, textures, and scents of every unique, irreplaceable being.

Creative work will enable us to sit first with a pine needle and later with a particular person. Schooled in empathy, connectedness, and communion by the pine needle, we will become porous and fluid, able to receive a particular person who is different and strange. Schooled by the pine needle, we will learn the name and face, the particular story, the unique gifts, the peculiar fears, and the concrete hopes of a particular other. Creative work thus generates the fundaments of love and community.

Sketching a pine needle may make it easier to sketch the particular life of a single African-American person and for the first time learn what a particular black life looks like. Only then will we know what's at stake when we say "black lives matter." Others of us will need to sit and sketch the life of a working-class, rural white man and learn about the seeds of his anger, fear, and alienation. Others of us will need to sit and sketch the life of a Muslim, a person suffering homelessness, a police officer, a single mom, or an LGBTQ person. All of us will need to sit and sketch our own particular lives, for these have become as foreign and dangerous to us as the lives of others.

This creative work will teach us the dangers of abstraction and facile generalizations that repress the moral sentiments and sever the affective bonds that knit our particular lives together into genuine community. Only when we have fully entered into the texture of another's particular life, will we learn what is lost by "all black people are...", "all white folk are...", "all blue-collar men do...", "every rich person is...", "all police officers do...". Such objectifying abstractions and weaponized generalizations are often defense mechanisms of our anxious, wounded, and fearful egos. Creativity and pine needles can help deliver us from them. And while we may eventually be able to make some helpful generalizations based on shared insight, we will make them more carefully, hold them more loosely, always testing them against the pine needles.

So, go, sketch a pine needle, that one, right there, right now; the one caught on the far side of a dangerous divide.

-----------------------------------

[1] Quoted in Douglas E. Christie, The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 29.

]]>

Big John, 2016

There stands Big John firm against the brilliant sky, tall and hollow, alone and happy. He's been there awhile now, along Highway 61 on the outskirts of town. It's hard to say whether he's coming or going. But he's a happy, abandoned relic in the roadside museum of American kitsch.

Yes, there he stands, an empty-armed mascot of a supermarket that once was but is no more. Big John is unburdened now, free of the fiberglass bags of groceries filled with myths that he once carried and free even of the supermarket itself that told him who he was: provider, breadwinner, hardworking family man who brought home the bacon.

A hundred yards to his north sits a boarded-up "gentleman's club," a "strip joint" in the unvarnished vernacular of working class men in blue jeans and tieless shirts like Big John. I wonder if Big John ever feels his hollowness on some of those dark, lonely nights along the Blues highway. I bet he's tempted to stumble in there, imagining himself a supersized Don Juan with a giant fistful of dollar bills in search of intimacy and companionship now that he is out of work and short on self-worth. But alas, his feet are bolted firmly to the ground.

A bit to his south is a fireworks stand where the crowds pull in to buy their freedom by the box. For a few bucks and weeks in midsummer, they can bask again in "the rocket's red glare" while waiting "for the dawn's early light." I wonder if Big John ever wants to swagger over there and light a few Whistling Petes or Roman Candles in the name of liberty, reliving the founding myth of bullets, bombs, and liberty one sparkler at a time. But alas, his feet are bolted firmly to the ground.

A dozen yards to his east is the ramp onto Highway 61, the way out of Dodge. I wonder if, short on work and meaning, lonely and disconnected, and bored with the the rituals of bullets and bombs, Big John ever longs just to "hit the road," to ride off into the sunset like a cowboy in search of a fresh start. But alas, his feet are bolted firmly to the ground.

Being tied down has saved Big John, saved him from himself and saved him for us. Being bolted down isn't so bad. Look, he still smiles and even has shiny shoes. And watching over the endless line of other cowboys on their way out of town seems good for the big soul of this grinning idiot.

Hey cowboy, as you whiz down Highway 61, pay attention to the kitsch. It can teach you more than it ever intended.

Poet, Minstrel, Muse, 2016

The shadow of Plato's Republic falls long across the imagination of western philosophy, theology, and spirituality. In it, Plato offers a vision of the good society centered in reason. In the well ordered polis, Philosopher-Kings and Guardians, attuned to the eternal forms far above the shadowy things of this material world, govern justly and order life benevolently for all.

In Plato's rationally ordered world, everyone has an assigned place, rank, and function. But curiously, the maintenance of this rationally ordered world also requires what Plato calls "a noble lie," a fiction created by the elite Guardians and taught to the masses to convince them to embrace their socially assigned place as natural, reasonable, and inevitable. The noble lie is a falsehood ostensibly generated and enacted in the interest of a greater good. The noble lie was a kind of propaganda that legitimated social rank and function by appealing to the different kinds of metal allegedly found in one's blood from birth. To step out of one's place was to deviate from one's metallic nature, to bend metal in unnatural and dangerous ways. Thus, the conflation of reason and social power were concealed by this "noble lie" internalized by the masses. [1]

What's also interesting is how suspicious Plato is of artists and poets. The good artists are craftspeople who should merely imitate in their art what they see in the world. Imitation rather than interpretation is the artist's calling. And curiously for Plato (but not for Aristotle after him), perceiving artistic beauty should be free of deep pleasure. Apparently, artists were to leave the heavy thinking of interpretation to the Philosopher-Kings, and all pleasure would eventually trickle down to the rest of us from their lofty heights. [2]

Having successfully house broken the visual artists, Plato turns to the poets and decides it better to banish them from his ideal republic. Poets are energized by the muses, those uncontrollable, mischievous agents of creativity with ties to the gods who disrupt things as they are, ignite the imagination to envision something new, different, and maybe even better. Poets traffic in metaphor, paradox, wordplay, lyric, story, riddle, and song, all of which are fraught with ambiguous meanings not easily wrestled to the ground by reason and good order, even when they are armed with the billy club of noble lies. [3]

When politics and community begin in reason but come to depend on noble lies to prop them up, whether in Plato's time or our own, there is cause for deep concern. Perhaps we in the United States have, in the interest of a reasonable and ordered society, embraced our own noble lie. We have asked women, the poor, people of color, Muslims, queer people, alienated working class white folk, and angry unemployed rural men, for example, to accept their marginalized rank and function as natural, inevitable, and reasonable. Our rational society demands the ordering of power and privilege found in the status quo. Embracing the noble lie allows us to render invisible the suffering and injustice masked by reason.

The problem with noble lies is that they are always tenuous, and require the multiplication of more lies to secure themselves. And when noble lies are finally exposed, it brings deep turmoil and struggle. Such well-worn, well-told lies always die a slow, tortured death that brings forth hate, rage, and violence as part of the grief of losing them.

Perhaps the danger of the poets and untamed artists is that they will expose the noble lie and the naked pretenses of reason. Wild-eyed, word-slinging poets might fire the imagination of their hearers toward other possibilities. Metaphors without crisp meaning but charged with evocative power might expose the fragility and limits of reason itself and indict the noble lie. Beauty might not be about mere imitation. Beauty might be about subversion, about new and never-before-imagined possibilities seizing hearts and minds and calling forth radical change. Beauty might trangress and erase the well chalked boundaries that demarcated order and privilege in our polis. Beauty might rescue people from the delusion of rational control and its noble fibs, or it might stir people to die trying. Poets fraternize with revolutionaries. They are always among the first to be purged in totalitarian states.

Plato was right. Poets (and undomesticated artists) are dangerous because they represented a volcanic eruption from beyond the world of rational control and noble lies; poets traffic in surprise and wonder, playfulness and laughter, all of which are subversive. They expose the hidden fissures of reason and in so doing challenge the distribution of social power and the structures of privilege often legitimated by appeals to seamless reason and its noble lies. Art touches mystery and transcendence, evokes new imaginative possibilities for the world, and tangles a robust affirmation of the goodness of the world with an equally robust criticism of the falseness that tries to erase it. Artists love to make visible what is invisible. They love to bend the metal found in earthen mines and fleshly veins into new things.

Perhaps this is part of why we need artists and their creative work so desperately in our own current, conflicted cultural moment where fear is driving us to desperate measures to preserve a status quo that seems ever so rational. But as in Plato's Republic, what's rational often needs a well-crafted, noble lie to prop it up. But even well-crafted, noble lies are dissolved by the beauty of artists and poets, because in the end, the Beautiful is always also the True and the Good.

If it is true that in times like these we most need artists and beauty, then its equally true that in times like these both are often least welcomed. In seasons of social turmoil, we convert art into propaganda, enlisting it strategically for our narrow cause. Unlike genuine art, propaganda dictates a one-dimensional meaning, corralling its sheep toward an overly simplified vision demanding unquestioning loyalty. It is reductionist, strategic, and coercive. Its line from art to action is far too straight and direct. It's clean edges stand false against the real world of jagged-edged ambiguity.

And when art and beauty cannot be enlisted for the cause by the propagandist, they are attacked as bourgeois distractions, escapist forms of sentimentality that make us privileged folk feel good while keeping our distance from the fray and struggle for justice. If art cannot be for us in propaganda, then it must be against us as luxurious, bourgeois escapism.

But the line between art and action is never as straight as the propagandist would like it to be. Nor is it so crooked and labyrinthine as to leave us lost in a dream world of illusion and escape.

Genuine art is far more powerful than propaganda or escapism. Genuine art and beauty work their muse-filled grace on the deep structures of our imagination, opening us to wonder, awe, and previously unconsidered possibilities. They awaken longing for and delight in the particularity of what is seen. When we enter meaningfully and briefly into the strange, new world of a poem or other work of art, we find ourselves delightfully lost there for a while. It has absorbed us the way a good story absorbs a listening child, and in so doing we find that we have joyfully given up our desperate grasp on the world, at least for a little while. Art draws us out of ourselves and away from the petty, acquisitive, self-serving, self-justifying egocentrism that all too often governs our actions, even those so easily cloaked in righteousness and reason.

Long before art issues in particular actions, it shapes our identity, character, and our most basic affective and cognitive attunement to all things. Encounters with beauty and artistry can dissolve the false self governed by anxiety, fear, hatred, and control and awaken a new self attuned to its own creatureliness, the joy of connectedness with all Being, and the longing for and delight that comes from participating in the mystery of life through the ordinary things of life. Long before beauty changes our individual actions and strategies, it changes our identities by rewriting the grand narrative that frames all things and grants them larger meaning.

And now we are back to Plato. Plato did fear the poets because they were propagandists or escapists. He feared them not because they changed actions in the short term or siphoned off our moral energies in escapism. He feared them for the right reason. He feared them because traffickers in beauty can trouble the universe as currently known and arranged. Beauty unsettles and transforms us, deeply, radically, and totally but usually gently, slowly, and seductively. New actions, of course, may and usually do follow upon such deep renovations of consciousness, but they are almost epiphenomenal it. What the poets bring is a revolution of imagination long before there is a revolution of action.

In our age of fear and hatred, desperate messianic politics, terrorism, and the weekly slaughter of those strange, unreasonable "others" aimed at preserving "law and order" and rechalking the lines of conventionality morality and social power, perhaps what we most need is to listen to the poets and artists, and to the gods whose bidding they do.

--------------------------

- Plato, The Republic. Trans. By C.D.C Reeve. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004), chapter 3, especially pp. 99-100.

- Kathryn B. Alexander, Saving Beauty: A Theological Aesthetics of Nature (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014), pp. 14-15.

- Cecilia González-Andrieu, Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2012), pp. 18-21.

]]>

The Point, Morro Rock, 2016

In his wonderful book, From Nature to Creation, theologian Norman Wirzba maintains that "how we name and narrate the world" is determinative for how we position ourselves in and relate to it. [1]

An illustration from Wirzba helps us to see his point. If I hold up before us a plant such as a dandelion and name it flower, we begin to interact with it as a beautiful and fragile thing, bright and fragrant, that pleases the senses. We are tempted to place the bright yellow flower in a vase of water on our dining table to enjoy during meals. It is an adornment worthy of care, attention, and delight.

However, if when holding up the same plant, I name it weed, we immediately see it as the enemy of our well manicured lawn. This weed is far from beautiful and fragrant; it is a nuisance. We don't enjoy it; we want to eradicate it, poison it even, in the interest of a uniformly green lawn.

Or still again, if when holding up the plant, I name it food, we immediately think of adding its leaves to a tossed salad to enrich the flavor. We will savor its slightly bitter contribution to the mix of fresh, delectable summer greens. And if we accept the witness offered by the menus of of fine restaurants, we will regard the consumption of dandelion leaves in our salads as a mark of a sophisticated palette.

Is the plant a thing of delight, an enemy, or a sophisticated food? Will we display, exterminate, or eat it? The choice to name it flower, weed, or food is at the same time a choice to locate it in one of several very different narratives of meaning that dramatically alter our cognitive, affective, and moral response to it. So, yes, "how we name and narrate the world" matters because it shapes dramatically different and often incompatible forms of life in response to it. [2]

In contemporary western civilizations, we name and narrate our world with the vocabulary of consumerism. We name ourselves I and narrate a story in which this isolated, autonomous self is the measure and meaning of reality. We enact our personhood through endless consumption. Other creatures are things, objects or commodities with little or no intrinsic value or sanctity. Things are raw materials waiting to be owned and possessed, used and consumed for my personal aggrandizement. The value of a thing is assigned by us, often by way of a price tag or through some other quantifier of its expendability and benefit to us. The problem with this naming and narration is that the appetite of the naming I is never sated, and we are trapped on a treadmill of utilitarian logic that demands more, bigger, cheaper, and easier. In this story, all creatures other than the self become things stripped of sanctity, lacking inherent worth, and thus unworthy of empathy or moral regard.

Not unlike the great religions of the world, artistic creativity and works of art can provide another way to name the plant. At their best, artists seek to name and narrate the world not as thing but as gift. [3]

Gifts, of course, can be and often are easily co-opted by the naming and narrating strategy of comsumerism. When that happens, they become thinly veiled transactions in which a gift given must be repaid by another gift of equal or greater value so as to balance the ledger of social power. Generosity, so the logic goes, is merely a mask for covertly exacting obligation, favor, or acquiesence from another. Better to pay back the debt to preserve one's autonomy.

But gifts need not become things pulled into the orbit of dominative power. To name the world and its creatures as gifts can to be recognize that all things ultimately come to us from beyond ourselves, including our very lives. Despite our efforts at denial, we are fragile creatures -- finite and radically dependent on realities given to us from beyond for daily survival. Gifts confront us of with the radical givenness of our lives and our utter dependence, moment by moment, on the unconditioned Whence and Whither of our existence. This is why receiving gifts can sometimes feel awkward.

Gifts also remind us of our inescapable interdependence with all other creatures. To give a gift is not simply to give someone a thing; a gift given is a call to membership, a summons to connectedness, and an invitation to deep participation in the mystery of the love and goodness that bind human beings, and indeed all beings, together in ways that are significantly resistant to commodification and market forces. We respond most faithfully to a gift by acknowledging with gratitude that vast web of natural, social, and divine integuments that binds all things together in mutuality and interdependence. Mystery and connectedness, dependence and interdependence, humility and gratitude lie back of and saturate this different economy of gifts. These qualities in turn open us to wonder, thanksgiving, and deep delight -- qualities of soul noticeably suppressed in the economy of things.

When painters daub pigment on a canvas, when sculpters collects bits of driftwood and fashion them into mobiles with string and wire that float in the breeze, when photographers record an ordered composition found amidst an overwhelming surplus of rocks, clouds, and trees, they are offering to themselves and their viewers a gift. Their creative act and piece of art are less an expression of their private inner life and more an invitation to a new imaginative way of naming, narrating, and thus relating to the world and its Source. For a moment, this gift of beauty can arrest our drive toward cognitive mastery and material control. We find ourselves lingering over it in delight, attending to its particularity with wonder, curiosity, puzzlement, and delight. To give up control, to linger, to experience curiosity, puzzlement, wonder, and deep delight are antithetical to the logic of control, efficiency, and utility that govern the cult of the thing.

Good art invites us into a dialogue with itself, and when the dialogue is genuine, it displaced us as the measure of all things. Such an artistic gift is never perfect, but in its own fragmentary way it summons us to see differently, to name and narrate the world in new, graced ways. We can be creatures again who acknowledge and embrace our own fragility and dependence on the universe of being. Ultimately, an experience of artistic beauty is an invitation to membership, connectedness, and participation in an expansive, cosmic community of being. In this community, the logic of scarcity, acquisitiveness, possession, and disposability is overcome by the logic of abundance, communion, mystery, and deep, lasting delight.

------------------------

1. Norman Wirzba, From Nature to Creation: A Christian Vision for Understanding and Loving the World (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2015).

2. Wirzba, pp. 18-19.

3. Wirzba, pp. 144-52. I am borrowing and adapting Wirzba's elaboration of gift. For a fuller discussion of the idea of artistic creativity and works of art as gifts, see also Lewis Hyde's The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World (New York: Vintage, 1979).

]]>

Surf at Moonstone Beach, 2016

|