On the Beautiful and the Sublime

Boulders in the Surf, 2017

I cannot photograph sound.

And yet, twice in the past year I have desired to do so. In January of last year, following a snow storm in the Sierra Nevadas, I journeyed up to Yosemite to photograph. I began my circuit of the Valley with a stop at Bridal Veil Falls. The footpath to the base of the falls was covered in several inches of treacherous ice. Most of the few visitors in the park who bothered to stop chose to forego the walk and view the falls from the safety of the parking lot. As I gingerly worked my way up to the base of the falls, I heard peals of thunder overhead. But the skies were blue. It was not thunder. It was the sound of large sheets of ice high above the falls cracking, breaking loose, and smashing against rocks on their way over the cataract. This strange, thunderous sound echoed sharply over the whole of Yosemite Valley.

And just a few mornings ago, I stood atop a rocky shelf along an isolated stretch of untamed Pacific coastline at Montaña de Oro State Park. It was a foggy morning, and again I heard the sound of thunder that was not thunder. It was the sound of large, submerged boulders on the shoreline being lifted and tossed violently against one another by the fierce waves of high tide.

There is something unsettling and eerily fascinating about this thunder of ice, rocks, and water. Immanuel Kant and the Romantic thinkers and artists of the nineteenth century would likely have categorized these encounters as experiences of the sublime. The sublime, they insisted, is different from the beautiful. The beautiful refers to things on a human scale -- small, delicate, pretty, and manageable by the mind. Experiences of beauty evoke an immediate sense of satisfaction and unalloyed pleasure as one perceived the presence of symmetry, form, and balance. Beauty awakens a sense of being at-home in the world. Beauty consoles, comforts, and reassures. The mind is up to the task of beauty.

Experiences of the sublime are different, insisted Kant and the Romantics. We experience the sublime when we are confronted and overwhelmed by the vast, unbounded, primal forces of the universe. When we experience the sublime, we are radically disoriented. We feel swallowed up by the vastness of cosmic forces and sense acutely our smallness and vulnerability in the grand scheme of things. For Kant, it was the vastness of "the starry sky above" that evoked a sense of the sublime. The power of ocean tides and echoing peals of thunder have the same effect. These experiences of boundlessness, displace and dislocate us, disrupting our cognitive powers. When they do, they evoke something other than a simple, direct sense of pleasure and at-homeness in the world. Instead, they pull us affectively in multiple, contrary directions all at once. [1]

Rudolf Otto, while writing about "the holy," might just as easily have been writing about the sublime. Otto characterized a holy object as a mysterium tremendum et fascinans. [2] Holy things are mysterious, "wholly other" things that confound the mind and evoke a sense of fear and fascination at the same time. We are drawn irresistibly across treacherous terrain to the cracking ice and jumbling boulders even as we pull back with caution and fear at their danger and disregard for us. The thunder of rocks, water, and ice calls out to us to come closer for a better look even as we know that with one misstep these elemental forces can kill us. To feel these countervailing impulses at once is a mark of the sublime.

This distinction between the beautiful and the sublime is not without its problems. Repeating the gender essentialism of patriarchy, for example, nineteenth-century thinkers identified beauty with the feminine and the sublime with the masculine. And while it was not their intention to diminish the significance of the beautiful in the interest of the sublime, such was often the effect in practice when the distinction became gendered. Patriarchy demands beautiful but subordinate women rather than sublime ones. The former please and serve men, while the latter threaten to undo them. [3]

And yet, despite the problematic overlay of patriarchy and gender essentialism, one senses an authentic insight here into some kinds of aesthetically charged experiences. Tangled and muddled by gender politics as this distinction is, we do, in fact, have these experiences of the sublime, and they are different from other experiences of beautiful things.

Such experiences of the sublime are powerfully formative. They shake us awake from the slumber of our grasping egocentrism. We discover that we are not the center, force, and fulcrum of the universe. We sense our smallness and vulnerability again, and paradoxically it is liberating. They free us from the compulsive drive to control reality, from the fear that drives us into the arms of false messiahs who promise to make us great again.

I cannot photograph the thunder of water, rock, and ice, and that fact is a palpable reminder that I am not the measure or even measurer of all things. But perhaps a photograph such as Boulders in the Surf can crudely and clumsily bear witness, even if only obliquely, to the sublime, to the fact that "we are saved in the end by the things that ignore us." [4]

-----------------------------------------

1. For a brief overview of the distinction between the beautiful and sublime in Kant and Romanticism, see Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and Being Just (Princeton: Princeton University Press), 82-6.

2. Rudolf Otto, The Idea of the Holy. Trans. John W. Harvey. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1923; 2nd ed., 1950 [Das Heilige, 1917].

3. For a more comprehensive critique of the distinction between beauty and the sublime, see Scarry, On Beauty, 82-6.

4. Anthony de Mello, One Minute Wisdom. Quoted in Belden Lane, The Solace of Fierce Landscapes: Desert and Mountain Spirituality (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1998), 57.

Why Beauty Matters

Train Cars, Rudyard, Mississippi, 2016

Ours is an age that has come to think of beauty and art as luxuries easily done without rather than as necessities required for living well.

Our willingness to dispense with them is written into much modern home construction and neighborhood development, for example, where our fetish for more and cheaper square footage and uniform design eclipses attention to the flow and arrangement of space, the presence or absence of natural light, and the unique, artful character imparted to a living space by careful attention to detail and variety. This impulse to dispense with beauty and art is also present in our educational institutions, where art programs are the first ones cut when budgets must be trimmed. The kids can do without paint, clay, and crayons, but they can't do without math and science, standardized tests, and computer skills, or so says the unimaginative "wisdom" of our age.

And on the few occasions when we finally turn in the direction of beauty, we easily get distracted by the pretty, by ornaments and decorations that lack depth or complexity. We want art that matches the couch rather than touches the soul. We confuse beauty with decor.

What exactly is lost when we slowly drift away from beauty and art?

Answering this question requires that we ask a more basic one, what makes a thing beautiful? Across the western intellectual tradition, the answers to this question has been complex and varied. But there is one aspect of the answers that recurs in nearly every age; and that is form. Form refers to the organizing principle of a thing, the integrative aspect that binds its parts into a harmonious whole. Form imparts orderly arrangement, coherence, and structure to an entity. A natural or artistic entity is beautiful when its various aspects are organized, integrated, and patterned harmoniously. Form expresses itself as the arrangement and order within a thing that make it a unified whole, something greater than the mere sum of its parts. Form sometimes goes by its Christian name, Logos, or by its Jewish name, Wisdom.

Form is what differentiates music from noise. If I drop my kitchen pots and pans on the floor, they will strike many of the same notes as the organist playing Beethoven's "Ode to Joy." But why is this noise rather than music? It is noise because the notes are not well ordered and harmoniously arranged. They lack proportion and symmetry, structure and coherence, integration and unity. The difference between "Ode to Joy" and clanging cookware is that the former has superior form while the latter lacks it almost entirely.

When we experience the form revealed in beauty, we feel down deep in our gut that the world in which we live is governed by order rather than chance, purpose rather than accident, pattern rather than chaos. In the presence of beauty, we sense deeply that our lives and the existence of all other things fit together in some coherent way that is ultimately meaningful. The experience of beauty awakens and intensifies that felt sense that the universal power that generates and integrates our lives is greater than the powers that seek to pull them apart. We are assured affectively that the universe is shot through with meaning, that its primal force is an integrative love, and that life is well lived when it consents to the harmony that binds all things together and yokes them to their transcendent purpose. Our native response to perceiving form in beautiful things centers in delight and joy that reorder the heart's deepest desires, drawing us out of ourselves toward the other in exuberant, spontaneous love.

To experience the form present in beauty is to hear a transcendent Witness declare that the world is good; that it is as it ought to be, and that there is room for us in it. The form of beauty awakens in us a sense of wellbeing, an intuitive, sure sense that the universe is not fundamentally hostile to our existence despite the reality of suffering in our lives. Beauty reveals the joyful truth that my life is never wholly my own own, that power and pose cannot ultimately trump goodness and truth. Form revealed in beauty exposes the lie that the only meaning my life has is whatever arbitrary meaning I or society assign it. The form manifested in beauty awakens hope, a sense of possibility, and a sense that life, love, and justice ultimately matter. Beauty thus gives birth to our moral imagination and awakens moral motivation.

In the end, the real danger of a beautyless, artless world is not so much ugliness but nihilism, the loss of that existential meaning that is bedrock to our humanity.

Pied Beauty

California Sea Otters, Mother and Pup, 2016

When I was a boy, I raised pigeons. I enjoyed releasing them many miles from home and finding that they had returned to the coop. On very rare occasions when two steel-grey homing pigeons mated, the plumage of their offspring was not at all like that of the parents. The parents had "thrown a pie" as pigeon-keepers called it. The plumage of the offspring was mottled, dappled in odd colors, and uniquely its own -- the wild resurgence of recessive genes. -MTM

|

Pied Beauty Glory be to God for dappled things-- For skies of couple-color as a brindled cow; For rose-moles all in stipple upon trout that swim; Fresh-firecoal chestnut-falls; finches' wings; Landscape plotted and pieced--fold, fallow, and plough; And all trades, their gear and tackle and trim.

All things counter, original, spare, strange; Whatever is fickle, freckled (who knows how?) With swift, slow; sweet, sour; adazzle, dim; He fathers-forth whose beauty is past change: Praise him.*

-Gerard Manley Hopkins, 1877 |

------------------------------

*This poem is in the public domain.

On Pine Needles and Politics

Toadstool and Pine Needles, 2013

In My First Summer in the Sierra (1911), John Muir offers the following account of sketching a sugar pine tree in the Sierra Nevada.

| I never weary of gazing at its grand tasseled cones, it's perfectly round bole one hundred feet or more without a limb, the fine a purplish color of its bark, and its magnificent outsweeping, down-curving feathery arms forming a crown always bold and striking an exhilarating... At the age of fifty to one hundred years it begins to acquire individuality, so that no two are alike in their prime or old age. Every tree calls for special admiration. I have been making many sketches, and regret that I cannot draw every needle. [1] |

In the midst of a creative act, Muir discovered that "no two [trees] are alike." So intense is his insight that he longs to sketch each and every pine needle because one cannot substitute for another without loss. Muir was smitten by the power of particularity.

Artmaking opens up this power of particularity in our lives, evoking a deeply felt sense of the irreducible uniqueness of the single thing in front of us right now. Under its spell, we linger over the minutest detail, offering it a long, loving, sensuous gaze. As we do, everything else fades temporarily from view. It is as though time stops and we are wholly absorbed in the intricacy of this and only this thing. We come to know it immediately, intimately, and vividly. We lose ourselves in it only to find ourselves again, but now we are richer for having been woven together intimately with the object and the felt mystery it makes present.

As we sketch, photograph, or paint the pine needle, we are so keenly focused on its particularity that the boundaries between subject and object dissolve. The anxiously patrolled borders of the self become porous, fluid, and elastic. The self relinquishes its drive to control -- physically, emotionally, and cognitively. The ego discovers itself open, receptive, and vulnerable. Curiosity dissolves control, empathy replaces hostility, love banishes indifference. Before the pine needle and the felt sense of mystery that envelops it, delight, wonder, and hospitality crowd out fear, hatred, or violence. The self makes room for the pine needle and allows it to be what it is, fragile, beautiful, vulnerable. And now loved.

This kind of artistic awareness is very much like the mystical awareness treasured by the contemplative traditions in nearly all of the great religions of the world. These are not experiences of flight from the world, from the ordinary, from the particular. Rather, they are experiences of a radically new way of being present to the world, to the ordinary, to the particular. When we linger over the beautiful thing, suddenly we and it are cradled in the arms of the Whole, the mysterious Whither and Whence of all being. We have celebrated Communion.

There is a deep paradox here, and it is this. When we severely restrict the scope of our attention to a single being, giving it our total attention and devotion, it becomes a portal onto the Whole. In seeing the one, we awaken to the All. Only by restricting our awareness does it become expansive and capacious. If it is Logos we find, it is always first incarnated.

This graced form of awareness is not the exclusive possession of professional artists or the mystical virtuosi. It is available to all of us, but we must cultivate it. Among the ways we do so is by exercising creativity, by making art. Many of us gave up artmaking when we grew up, shamed out of it by the demands of adulthood and "serious" living. But creativity and art-making are deeply spiritual, transformative practices, capable of renovating our imaginations and reorienting our total affective and cognitive posture toward life over time. When we neglect them in our adult lives, we do so at our own peril.

But what do pine needles have to do with politics? At this moment in American political life, we are a deeply divided people. Beneath our political, cultural turmoil is a deeper spiritual turmoil. We are a people governed by fear, alienation, and isolation. Our fractious politics and lack of empathetic connection to one another are a symptom of our traumatized souls. We are closed off from one another and from ourselves -- angry, alienated, and desperately in search of political messiahs from any end of the political spectrum who we hope will magically rescue us from our problems. But down deep we know that no politician, party, platform, or election will do for our souls what needs doing.

What is required is work rather than magic, and it is work that we the people rather than a single political messiah must do. It's local, particular, grassroots work. It's slow, hard, and risky work. And, as silly and naive as it may sound, I believe that some of this work must be the joyful work of making art. We need to discover or rediscover the bliss of creativity. We need to sketch, photograph, and paint that pine needle right there, right now. We need to do this creative work so that we might discover the transformative power of particularity. Attending deeply to this pine needle, the one right there in front of us now, is one way of practicing ourselves into openness and receptivity to the distinctive colors, qualities, textures, and scents of every unique, irreplaceable being.

Creative work will enable us to sit first with a pine needle and later with a particular person. Schooled in empathy, connectedness, and communion by the pine needle, we will become porous and fluid, able to receive a particular person who is different and strange. Schooled by the pine needle, we will learn the name and face, the particular story, the unique gifts, the peculiar fears, and the concrete hopes of a particular other. Creative work thus generates the fundaments of love and community.

Sketching a pine needle may make it easier to sketch the particular life of a single African-American person and for the first time learn what a particular black life looks like. Only then will we know what's at stake when we say "black lives matter." Others of us will need to sit and sketch the life of a working-class, rural white man and learn about the seeds of his anger, fear, and alienation. Others of us will need to sit and sketch the life of a Muslim, a person suffering homelessness, a police officer, a single mom, or an LGBTQ person. All of us will need to sit and sketch our own particular lives, for these have become as foreign and dangerous to us as the lives of others.

This creative work will teach us the dangers of abstraction and facile generalizations that repress the moral sentiments and sever the affective bonds that knit our particular lives together into genuine community. Only when we have fully entered into the texture of another's particular life, will we learn what is lost by "all black people are...", "all white folk are...", "all blue-collar men do...", "every rich person is...", "all police officers do...". Such objectifying abstractions and weaponized generalizations are often defense mechanisms of our anxious, wounded, and fearful egos. Creativity and pine needles can help deliver us from them. And while we may eventually be able to make some helpful generalizations based on shared insight, we will make them more carefully, hold them more loosely, always testing them against the pine needles.

So, go, sketch a pine needle, that one, right there, right now; the one caught on the far side of a dangerous divide.

-----------------------------------

[1] Quoted in Douglas E. Christie, The Blue Sapphire of the Mind: Notes for a Contemplative Ecology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2013), p. 29.

Alas, His Feet Are Bolted Firmly to the Ground

Big John, 2016

There stands Big John firm against the brilliant sky, tall and hollow, alone and happy. He's been there awhile now, along Highway 61 on the outskirts of town. It's hard to say whether he's coming or going. But he's a happy, abandoned relic in the roadside museum of American kitsch.

Yes, there he stands, an empty-armed mascot of a supermarket that once was but is no more. Big John is unburdened now, free of the fiberglass bags of groceries filled with myths that he once carried and free even of the supermarket itself that told him who he was: provider, breadwinner, hardworking family man who brought home the bacon.

A hundred yards to his north sits a boarded-up "gentleman's club," a "strip joint" in the unvarnished vernacular of working class men in blue jeans and tieless shirts like Big John. I wonder if Big John ever feels his hollowness on some of those dark, lonely nights along the Blues highway. I bet he's tempted to stumble in there, imagining himself a supersized Don Juan with a giant fistful of dollar bills in search of intimacy and companionship now that he is out of work and short on self-worth. But alas, his feet are bolted firmly to the ground.

A bit to his south is a fireworks stand where the crowds pull in to buy their freedom by the box. For a few bucks and weeks in midsummer, they can bask again in "the rocket's red glare" while waiting "for the dawn's early light." I wonder if Big John ever wants to swagger over there and light a few Whistling Petes or Roman Candles in the name of liberty, reliving the founding myth of bullets, bombs, and liberty one sparkler at a time. But alas, his feet are bolted firmly to the ground.

A dozen yards to his east is the ramp onto Highway 61, the way out of Dodge. I wonder if, short on work and meaning, lonely and disconnected, and bored with the the rituals of bullets and bombs, Big John ever longs just to "hit the road," to ride off into the sunset like a cowboy in search of a fresh start. But alas, his feet are bolted firmly to the ground.

Being tied down has saved Big John, saved him from himself and saved him for us. Being bolted down isn't so bad. Look, he still smiles and even has shiny shoes. And watching over the endless line of other cowboys on their way out of town seems good for the big soul of this grinning idiot.

Hey cowboy, as you whiz down Highway 61, pay attention to the kitsch. It can teach you more than it ever intended.

On the Danger of Poets and Noble Lies

Poet, Minstrel, Muse, 2016

The shadow of Plato's Republic falls long across the imagination of western philosophy, theology, and spirituality. In it, Plato offers a vision of the good society centered in reason. In the well ordered polis, Philosopher-Kings and Guardians, attuned to the eternal forms far above the shadowy things of this material world, govern justly and order life benevolently for all.

In Plato's rationally ordered world, everyone has an assigned place, rank, and function. But curiously, the maintenance of this rationally ordered world also requires what Plato calls "a noble lie," a fiction created by the elite Guardians and taught to the masses to convince them to embrace their socially assigned place as natural, reasonable, and inevitable. The noble lie is a falsehood ostensibly generated and enacted in the interest of a greater good. The noble lie was a kind of propaganda that legitimated social rank and function by appealing to the different kinds of metal allegedly found in one's blood from birth. To step out of one's place was to deviate from one's metallic nature, to bend metal in unnatural and dangerous ways. Thus, the conflation of reason and social power were concealed by this "noble lie" internalized by the masses. [1]

What's also interesting is how suspicious Plato is of artists and poets. The good artists are craftspeople who should merely imitate in their art what they see in the world. Imitation rather than interpretation is the artist's calling. And curiously for Plato (but not for Aristotle after him), perceiving artistic beauty should be free of deep pleasure. Apparently, artists were to leave the heavy thinking of interpretation to the Philosopher-Kings, and all pleasure would eventually trickle down to the rest of us from their lofty heights. [2]

Having successfully house broken the visual artists, Plato turns to the poets and decides it better to banish them from his ideal republic. Poets are energized by the muses, those uncontrollable, mischievous agents of creativity with ties to the gods who disrupt things as they are, ignite the imagination to envision something new, different, and maybe even better. Poets traffic in metaphor, paradox, wordplay, lyric, story, riddle, and song, all of which are fraught with ambiguous meanings not easily wrestled to the ground by reason and good order, even when they are armed with the billy club of noble lies. [3]

When politics and community begin in reason but come to depend on noble lies to prop them up, whether in Plato's time or our own, there is cause for deep concern. Perhaps we in the United States have, in the interest of a reasonable and ordered society, embraced our own noble lie. We have asked women, the poor, people of color, Muslims, queer people, alienated working class white folk, and angry unemployed rural men, for example, to accept their marginalized rank and function as natural, inevitable, and reasonable. Our rational society demands the ordering of power and privilege found in the status quo. Embracing the noble lie allows us to render invisible the suffering and injustice masked by reason.

The problem with noble lies is that they are always tenuous, and require the multiplication of more lies to secure themselves. And when noble lies are finally exposed, it brings deep turmoil and struggle. Such well-worn, well-told lies always die a slow, tortured death that brings forth hate, rage, and violence as part of the grief of losing them.

Perhaps the danger of the poets and untamed artists is that they will expose the noble lie and the naked pretenses of reason. Wild-eyed, word-slinging poets might fire the imagination of their hearers toward other possibilities. Metaphors without crisp meaning but charged with evocative power might expose the fragility and limits of reason itself and indict the noble lie. Beauty might not be about mere imitation. Beauty might be about subversion, about new and never-before-imagined possibilities seizing hearts and minds and calling forth radical change. Beauty might trangress and erase the well chalked boundaries that demarcated order and privilege in our polis. Beauty might rescue people from the delusion of rational control and its noble fibs, or it might stir people to die trying. Poets fraternize with revolutionaries. They are always among the first to be purged in totalitarian states.

Plato was right. Poets (and undomesticated artists) are dangerous because they represented a volcanic eruption from beyond the world of rational control and noble lies; poets traffic in surprise and wonder, playfulness and laughter, all of which are subversive. They expose the hidden fissures of reason and in so doing challenge the distribution of social power and the structures of privilege often legitimated by appeals to seamless reason and its noble lies. Art touches mystery and transcendence, evokes new imaginative possibilities for the world, and tangles a robust affirmation of the goodness of the world with an equally robust criticism of the falseness that tries to erase it. Artists love to make visible what is invisible. They love to bend the metal found in earthen mines and fleshly veins into new things.

Perhaps this is part of why we need artists and their creative work so desperately in our own current, conflicted cultural moment where fear is driving us to desperate measures to preserve a status quo that seems ever so rational. But as in Plato's Republic, what's rational often needs a well-crafted, noble lie to prop it up. But even well-crafted, noble lies are dissolved by the beauty of artists and poets, because in the end, the Beautiful is always also the True and the Good.

If it is true that in times like these we most need artists and beauty, then its equally true that in times like these both are often least welcomed. In seasons of social turmoil, we convert art into propaganda, enlisting it strategically for our narrow cause. Unlike genuine art, propaganda dictates a one-dimensional meaning, corralling its sheep toward an overly simplified vision demanding unquestioning loyalty. It is reductionist, strategic, and coercive. Its line from art to action is far too straight and direct. It's clean edges stand false against the real world of jagged-edged ambiguity.

And when art and beauty cannot be enlisted for the cause by the propagandist, they are attacked as bourgeois distractions, escapist forms of sentimentality that make us privileged folk feel good while keeping our distance from the fray and struggle for justice. If art cannot be for us in propaganda, then it must be against us as luxurious, bourgeois escapism.

But the line between art and action is never as straight as the propagandist would like it to be. Nor is it so crooked and labyrinthine as to leave us lost in a dream world of illusion and escape.

Genuine art is far more powerful than propaganda or escapism. Genuine art and beauty work their muse-filled grace on the deep structures of our imagination, opening us to wonder, awe, and previously unconsidered possibilities. They awaken longing for and delight in the particularity of what is seen. When we enter meaningfully and briefly into the strange, new world of a poem or other work of art, we find ourselves delightfully lost there for a while. It has absorbed us the way a good story absorbs a listening child, and in so doing we find that we have joyfully given up our desperate grasp on the world, at least for a little while. Art draws us out of ourselves and away from the petty, acquisitive, self-serving, self-justifying egocentrism that all too often governs our actions, even those so easily cloaked in righteousness and reason.

Long before art issues in particular actions, it shapes our identity, character, and our most basic affective and cognitive attunement to all things. Encounters with beauty and artistry can dissolve the false self governed by anxiety, fear, hatred, and control and awaken a new self attuned to its own creatureliness, the joy of connectedness with all Being, and the longing for and delight that comes from participating in the mystery of life through the ordinary things of life. Long before beauty changes our individual actions and strategies, it changes our identities by rewriting the grand narrative that frames all things and grants them larger meaning.

And now we are back to Plato. Plato did fear the poets because they were propagandists or escapists. He feared them not because they changed actions in the short term or siphoned off our moral energies in escapism. He feared them for the right reason. He feared them because traffickers in beauty can trouble the universe as currently known and arranged. Beauty unsettles and transforms us, deeply, radically, and totally but usually gently, slowly, and seductively. New actions, of course, may and usually do follow upon such deep renovations of consciousness, but they are almost epiphenomenal it. What the poets bring is a revolution of imagination long before there is a revolution of action.

In our age of fear and hatred, desperate messianic politics, terrorism, and the weekly slaughter of those strange, unreasonable "others" aimed at preserving "law and order" and rechalking the lines of conventionality morality and social power, perhaps what we most need is to listen to the poets and artists, and to the gods whose bidding they do.

--------------------------

- Plato, The Republic. Trans. By C.D.C Reeve. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 2004), chapter 3, especially pp. 99-100.

- Kathryn B. Alexander, Saving Beauty: A Theological Aesthetics of Nature (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2014), pp. 14-15.

- Cecilia González-Andrieu, Bridge to Wonder: Art as a Gospel of Beauty (Waco: Baylor University Press, 2012), pp. 18-21.

Of Dandelions

The Point, Morro Rock, 2016

In his wonderful book, From Nature to Creation, theologian Norman Wirzba maintains that "how we name and narrate the world" is determinative for how we position ourselves in and relate to it. [1]

An illustration from Wirzba helps us to see his point. If I hold up before us a plant such as a dandelion and name it flower, we begin to interact with it as a beautiful and fragile thing, bright and fragrant, that pleases the senses. We are tempted to place the bright yellow flower in a vase of water on our dining table to enjoy during meals. It is an adornment worthy of care, attention, and delight.

However, if when holding up the same plant, I name it weed, we immediately see it as the enemy of our well manicured lawn. This weed is far from beautiful and fragrant; it is a nuisance. We don't enjoy it; we want to eradicate it, poison it even, in the interest of a uniformly green lawn.

Or still again, if when holding up the plant, I name it food, we immediately think of adding its leaves to a tossed salad to enrich the flavor. We will savor its slightly bitter contribution to the mix of fresh, delectable summer greens. And if we accept the witness offered by the menus of of fine restaurants, we will regard the consumption of dandelion leaves in our salads as a mark of a sophisticated palette.

Is the plant a thing of delight, an enemy, or a sophisticated food? Will we display, exterminate, or eat it? The choice to name it flower, weed, or food is at the same time a choice to locate it in one of several very different narratives of meaning that dramatically alter our cognitive, affective, and moral response to it. So, yes, "how we name and narrate the world" matters because it shapes dramatically different and often incompatible forms of life in response to it. [2]

In contemporary western civilizations, we name and narrate our world with the vocabulary of consumerism. We name ourselves I and narrate a story in which this isolated, autonomous self is the measure and meaning of reality. We enact our personhood through endless consumption. Other creatures are things, objects or commodities with little or no intrinsic value or sanctity. Things are raw materials waiting to be owned and possessed, used and consumed for my personal aggrandizement. The value of a thing is assigned by us, often by way of a price tag or through some other quantifier of its expendability and benefit to us. The problem with this naming and narration is that the appetite of the naming I is never sated, and we are trapped on a treadmill of utilitarian logic that demands more, bigger, cheaper, and easier. In this story, all creatures other than the self become things stripped of sanctity, lacking inherent worth, and thus unworthy of empathy or moral regard.

Not unlike the great religions of the world, artistic creativity and works of art can provide another way to name the plant. At their best, artists seek to name and narrate the world not as thing but as gift. [3]

Gifts, of course, can be and often are easily co-opted by the naming and narrating strategy of comsumerism. When that happens, they become thinly veiled transactions in which a gift given must be repaid by another gift of equal or greater value so as to balance the ledger of social power. Generosity, so the logic goes, is merely a mask for covertly exacting obligation, favor, or acquiesence from another. Better to pay back the debt to preserve one's autonomy.

But gifts need not become things pulled into the orbit of dominative power. To name the world and its creatures as gifts can to be recognize that all things ultimately come to us from beyond ourselves, including our very lives. Despite our efforts at denial, we are fragile creatures -- finite and radically dependent on realities given to us from beyond for daily survival. Gifts confront us of with the radical givenness of our lives and our utter dependence, moment by moment, on the unconditioned Whence and Whither of our existence. This is why receiving gifts can sometimes feel awkward.

Gifts also remind us of our inescapable interdependence with all other creatures. To give a gift is not simply to give someone a thing; a gift given is a call to membership, a summons to connectedness, and an invitation to deep participation in the mystery of the love and goodness that bind human beings, and indeed all beings, together in ways that are significantly resistant to commodification and market forces. We respond most faithfully to a gift by acknowledging with gratitude that vast web of natural, social, and divine integuments that binds all things together in mutuality and interdependence. Mystery and connectedness, dependence and interdependence, humility and gratitude lie back of and saturate this different economy of gifts. These qualities in turn open us to wonder, thanksgiving, and deep delight -- qualities of soul noticeably suppressed in the economy of things.

When painters daub pigment on a canvas, when sculpters collects bits of driftwood and fashion them into mobiles with string and wire that float in the breeze, when photographers record an ordered composition found amidst an overwhelming surplus of rocks, clouds, and trees, they are offering to themselves and their viewers a gift. Their creative act and piece of art are less an expression of their private inner life and more an invitation to a new imaginative way of naming, narrating, and thus relating to the world and its Source. For a moment, this gift of beauty can arrest our drive toward cognitive mastery and material control. We find ourselves lingering over it in delight, attending to its particularity with wonder, curiosity, puzzlement, and delight. To give up control, to linger, to experience curiosity, puzzlement, wonder, and deep delight are antithetical to the logic of control, efficiency, and utility that govern the cult of the thing.

Good art invites us into a dialogue with itself, and when the dialogue is genuine, it displaced us as the measure of all things. Such an artistic gift is never perfect, but in its own fragmentary way it summons us to see differently, to name and narrate the world in new, graced ways. We can be creatures again who acknowledge and embrace our own fragility and dependence on the universe of being. Ultimately, an experience of artistic beauty is an invitation to membership, connectedness, and participation in an expansive, cosmic community of being. In this community, the logic of scarcity, acquisitiveness, possession, and disposability is overcome by the logic of abundance, communion, mystery, and deep, lasting delight.

------------------------

1. Norman Wirzba, From Nature to Creation: A Christian Vision for Understanding and Loving the World (Grand Rapids: Baker Academic, 2015).

2. Wirzba, pp. 18-19.

3. Wirzba, pp. 144-52. I am borrowing and adapting Wirzba's elaboration of gift. For a fuller discussion of the idea of artistic creativity and works of art as gifts, see also Lewis Hyde's The Gift: Creativity and the Artist in the Modern World (New York: Vintage, 1979).

Spilled Beauty

Surf at Moonstone Beach, 2016

|

"… [W]hatever is and whatever comes to be, is and comes to be on account of the beautiful and the good. All things look to it; all things are moved by it; all things are held together by it. Every source…exists for the sake of it, because of it, and in it; simply put, every source, all preservation and all ending, whatever is held in being, derives from the beautiful and the good. Hence, all things must desire, must yearn for, must love the beautiful and the good; because of it and for its sake, the weaker is returned with yearning to the more powerful, equals keep fellowship with equals, the more powerful become providential toward the weaker, and each brings forth itself; everything does and wills whatever it does and wills by desire for the beautiful and the good." --Dionysius the Pseudo-Areopagite, The Divine Names, 4.10, unpublished translation by Kendra G. Hotz

|

In the writings of the sixth-century Christian mystic known as the Pseudo-Dionysius (or "Denys"), we find a suggestive vision of the human condition. When Denys surveyed the human landscape, he concluded that our condition is one marked by a fragmentation and restlessness that undermine stable, integrated personhood. The tragedy of our condition resides not so much in disobedience and guilt but in pervasively distorted desire. To be human is to be an erotic being, where eros refers not primarily to sexuality but to the integrative pattern of yearning and desire that draws together our identities and orients us to all reality. Denys claims that before our fall into this tragic state, the desire that constitutes our personhood was like a single mirror that reflected a unified vision of life focused on the Divine. This singularity of focus ordered our identity so that the various desires of the soul and body were brought into homeostatic balance and harmony, ensuring, for example, that our sexual desire, our desire for food, our desire for companionship, our desire for work, our desire to own, use, and enjoy things, and our desire for God, were integrated into a carefully orchestrated, interdependent unity that brought wholeness, beauty, and harmony to all of life.

The Fall shattered that mirror into thousands of disconnected shards, each reflecting a diverse, discrete object of desire. A unified, integrated self became a fragmented, dislocated self drifting anxiously among a variety of disconnected things desperately investing each of them with an ultimacy that none of them could bear. The tragic consequence of this is not primarily guilt but personal disintegration, chaotic restlessness, contradictory and confused desires, alienation from self, and exile from the world of authentic relationships with God and others.

What has come to interest me as a theologian and photographic artist is the way that consumerism as the prevailing meaning-making system of our world reflects and answers to this ancient theology. Consumerism is more than an economic system. It is the totalizing ideology or, if theologian John Kavanaugh is right, the prevailing religion, of American life that has soaked deeply into our bones, shaping our individual and communal perceptions, values, actions, and assumptions in ways we usually remain blind to.*

Consumerism depends on the fragmentation and distortion of our desire, the elusiveness of fulfillment, the addiction-producing ache of incompleteness, and the illusion that finite objects will do for us what only the Infinite can do. To produce, buy, and consume are its ethical mandate. Competition, possession, and egocentrism are its cardinal virtues. Shopping is salvific, and cheap, fast, and convenient are the tropes of its over-marketed liturgy. More is its great eschatological hope and Santa Claus its patron saint.

A constant stream of new and improved products are paraded before us, each promising to do for us what the last one failed to do. Each reminds us of our insufficiency even as it offers a faux redemption from it coated with ersatz ultimacy. Infiniti is yours as a luxury sedan made by Nissan, and Eternity is bottled as a $42 cologne by Calvin Klein. Buy her earrings from De Beers Jewelry and like the silhouetted selves in the televised commercial you and your beloved will slip into the dark bedroom lit only by the sparkle of diamonds and rediscover your lost intimacy, sexual passion, and marital concord. You'll be a real man again, a provider for your woman, and she'll rediscover the power of things to narcotize the pain and diminishment of selfhood required by patriarchy.

I am more and more convinced that the pursuit of creativity and beauty in the arts can be one of the ways back to a unified, concentrated form of desire where integration overcomes fragmentation. Like prayer, sacraments, and other contemplative practices, artistic creativity and viewing works of art can become effective, albeit clumsy, efforts at coherence, wholeness, and connectedness in a consumerist world governed by divided desires, transient allegiances, and false objects of ultimacy. To be sure, efforts at creativity and beauty can be and often have been co-opted by consumerism, but at there best, they can form part of our strategy for resistance and the rediscovery of wholeness, well ordered living, and authenticity.

Artistic creativity and the thirst for beauty emerge out of an ordinary person's longing for connectedness and coherence, out of a longing to discern and bear witness to a larger underlying unity capable of stitching the fragmentary episodes of our individual and shared lives into a single, grand epic penned by that mysterious Other "in whom we live, move, and have our being." Art and beauty are an invitation to see, hear, touch, move, and ultimately live differently.

Good photographs or other good works of art can serve as portals through which we briefly glimpse the primordial unity that upholds and expresses itself through all things. But even this glimpse, brief, distant and oblique as it is, is enough to teach us that beauty is not simply there to entertain us. It is there to restore us, to occasion both the reintegration of the self and our reconciliation with others and with the Wholly Other that always seem to elude us in the fragmenting world of consumerism. Beauty has this power because it is ontologically real and because it is a concretization of divine grace.

Artistic creativity can be a gesture, albeit a halting, partial, and clumsy one, that points us toward the simple truth that beauty is Gospel spilled lavishly on the world.

-----------------------------------------

*John F. Kavanaugh, Following Christ in a Consumer Society: The Spirituality of Cultural Resistance (25th Anniversary Edition, New York: Orbis Books, 2006)

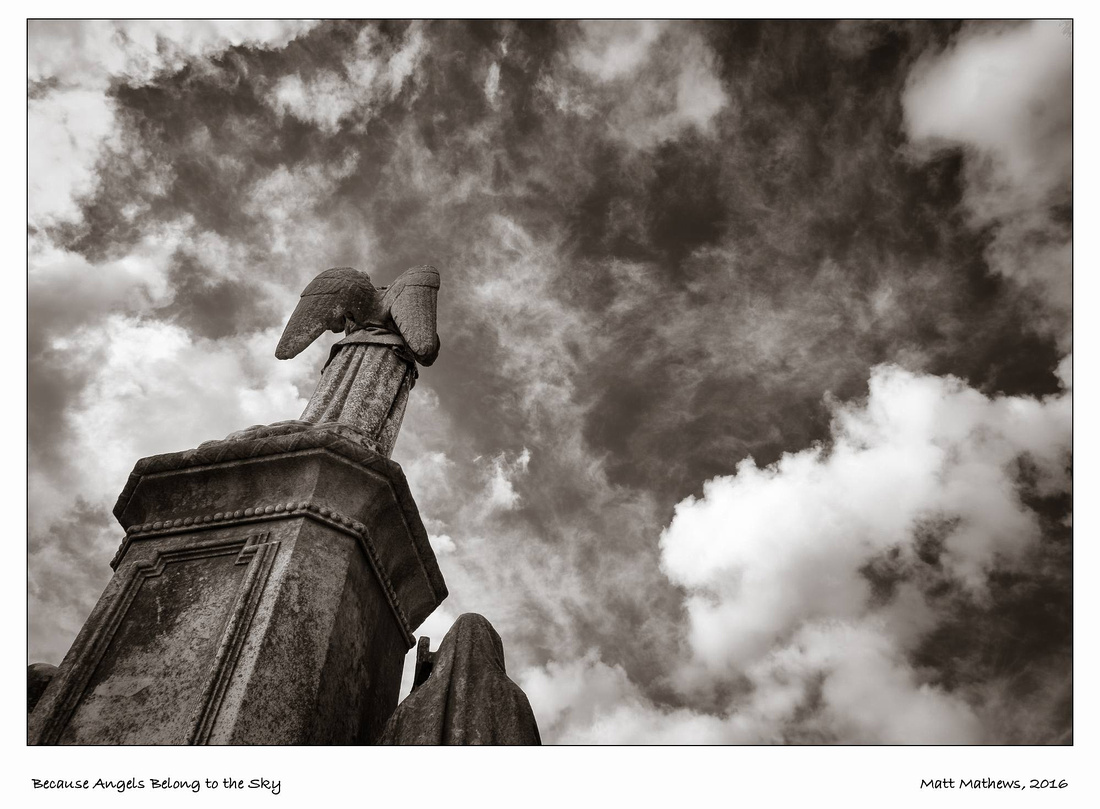

Because Angels Belong to the Sky

During 2016, I am serving as the David McCrosky Photographer-in-Residence at historic Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee. I have photographed at Elmwood for many years, but not with the frequency or intensity that now accompany my role there.

Elmwood Cemetery is many things. It is the resting place of countless citizens of the city, many of whom shaped its life deeply and even more who did not. This is no indictment of the latter, but its own kind of praise.

When I walk among the eighty acres of statuary at Elmwood, I find myself pulled in two directions. I am first drawn to the large, exotic statuary inflected with a heavy Victorian accent -- towering angels, childlike cherubs, angelic nymphs, stern-faced busts, inscriptions of florid prose and sacred verse. There is even a lexicon of symbols, garlands, flowers, obelisks, pillars, and cisterns that translate into stone the nineteenth-century language of death. It is a beautiful sight to behold, and a photographer's playground.

And yet, there is another side to walking at Elmwood that draws me as well. It involves seeing the gravestones of the average people, the ordinary folk whose graves are easily overlooked amid the extravagance of the Victorian garden with its hovering flock of angels. These are the gravestones of infants and children, often small and nameless, bearing only the word, daughter or son, or in some cases, only two initials. And then there are other gravestones, many broken and fallen, whose letters have become unreadable, worn smooth and indistinct by a hundred or more years of weather. And still again, there are the more recent, plain gravestones bearing only names and dates, as noticeably short on sentiment as they are on aesthetic appeal. It is easy to walk past these rather plain, functional memorials in search of the angels, generals, mayors, Civil War soldiers, Memphis's first black millionaire, and the martyred Episcopal nuns of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878.

This visual tension created by the variety of memorials awakens ambivalence in me. The most ornate gravestones and memorials are there to coach our memory about the people at rest beneath them. Such coaching, of course, is as notoriously lopsided as the markers themselves, many of which, like little leaning Towers of Pisa, have settled with time and now stand awkward and crooked. If we are honest, we know that these folk were not as angelic as the stonework above them suggests. They trafficked as much in power as in virtue. And yet, we or their loved ones prefer to re-remember them angelically, at least for awhile, until grief is far enough distant to allow for honesty.

But then there are those ordinary markers of the average folk, the graves of a sort of blue-collar dead people. Their gravestones coach us less, leaving us only with naked facts, a name with only the dates of birth and death etched artlessly on unadorned stones that look mass produced. Perhaps these are the more honest memorials, seeking only to mark an ordinary life lived and lost. They make no bid at angelic re-remembering. There is no effort to win for the ones below a redemption from all ambiguity and ordinariness. Unlike the large crypts and towering memorials that punctuate the cemetery around them, these smaller, plain markers seem to make no claim at immortality through stone. But surely, the lives of those beneath them were as full as the lives of the white-collar dead people who seem to hold them hostage in the cemetery. Surely their loves were as deep, their hopes as intense, their joys as real, their suffering as intense, and their families as important as those of the angels.

When I walk and photograph at Elmwood, I am drawn to both kinds of markers. As a photographer, I am drawn to the memorials adorned in Victorian excess, desperately seeking to coach our memory of the dead and achieve for them a kind of immortality in stone. I need them because I know that the same longing for recognition and permanence and the same temptation toward antiseptic memory well up in every human heart, my own included. As a theologian, I am drawn to the plain markers of the average people, for they offer a more realistic assessment of our days and lives. There is no attempt to accomplish in stone what they did not accomplish in life. They lived and loved, worked and played, and celebrated and lamented like I do. And then they died. And so will I.

As lovely as the angels are, we are not them. We belong to the earth below with all of the ambiguities, possibilities, and partialities ingredient in ordinary flesh.

In the end, it is only the angels who belong to the sky.

Desire and Silent Rebellion

"Our hearts are restless until they find their rest in thee, O God."

"Our hearts are restless until they find their rest in thee, O God."

-Augustine, Confessions, Bk. 1, Ch. 1.

"...[A]s [the human] will is attracted or repelled by the variety of things..., so is it changed or converted..."

-Augustine, The City of God, Bk. 14, Ch. 6.

Human beings are shot through with desire. We hunger and thirst, ache for companionship and burn with sexual desire, and we long for things, some good, some bad, most a tangle of both. Augustine knew that human beings do not merely have desires; we become what we desire. The objects of our desire shape us into the kinds of people we become. What we desire hones our attention and forms our habits, blinding us to some things, highlighting others. How we see, what we see, and who we become are intimately and complexly commingled. So, while it is true that we have desires; it is perhaps more true to say that our desires have us. We become what we desire.

The windows along Main Street are intimately connected to this economy of human desire. In them we see things and promised experiences vying for our dollars, time, and loyalty. The carefully arranged tableaus and mannequins, collections of curios, well chosen words, and price tags are not simply selling things; they are seducing us with a vision of fully satisfied human desire.

The windows offer a kind of ersatz salvation, and much of the power of consumerism lies precisely here. While it purports simply to be meeting our desires, consumerism in fact creates those desires, shaping and reshaping them ever anew by holding before us an endless array of new and improved things to be easily acquired. The power of consumerism is not so much that it offers an array of things to satisfy our natural desires for food, shelter, clothing, recreation, and companionship. Rather, the power of consumerism resides in its capacity to redirect and exaggerate these desires by attaching them to things that have been imaginatively resignified to become bearers of an elusive but powerful vision of perfect human fulfillment.

While consumerism promises perfect fulfillment, that after all accounts for its irrestibility, it in fact depends upon the continued disappointment with the things we already own to fuel a fresh and even more intense desire to acquire the latest things. Buying the lingerie found on unrealistically lithe mannequins in boutique windows will make your body desirable again in his eyes. You will be young again. You will be thin again. You will be loved again. Buying the oversized truck found in the walk-in windows at the dealership and advertised with the deep, husky male voice in the electronic window on your living room wall will settle questions about your masculinity. You'll be man enough for her. You will be loved again. Buy the larger home pictured in the windows of the real estate office and fill it with this season's newest furnishings from the furniture store windows, and your family will know domestic bliss, and your neighbors will know your social worth. Order from the menu in the window of the trendy restaurant or buy her a diamond from the jewelry case, and the spark of romance and sexual excitement will return.

While the windows of Main Street proclaim a carefully marketed gospel of commodified desire, these same windows are engaged in a silent rebellion. If you look at them rather than through them, if you look at the play of reflections with their odd juxtaposition of elements from the street that superimpose themselves upon the carefully choreographed tableaus of the marketers, you see their silent rebellion. Street signs, blurred faces with unguarded expressions, inverted words, cars, pavement, paint, and foreign signage crash disruptively into the carefully planned, controlled scenes behind the glass. Sunlight glints unpredictably and the changing play of clouds and sky appear and reappear unpredictably minute by minute. If you pay attention to the reflections, you can too easily overlook the message behind the glass. And when that happens, the windows have won their rebellion.

Despite every attempt to control what we see in them, and despite every attempt to create and direct our desire through what is seen in them, the windows won't fully cooperate. In the play of reflections, we find accidental beauty, visual riddles replacing the marketer's confident slogans, indeterminate visual possibilities that can free our imagination and liberate desire from the lie of owned things.

Yes, the windows are engaged in a silent rebellion against those who would control them, and through them, control us.

The Shattering of the Vessels

In the sixteenth-century writings of the Jewish mystic, Rabbi Isaac Luria Safed (1534-72) there is an intriguing creation story known as "The Shattering of the Vessels."

God, the story goes, created the world by pouring primordial, divine light into ten fragile vessels that would become the world. The primordial light -- the bearer of all beauty, goodness, and righteousness -- however, was simply too much for the fragile vessels, and they shattered into many shards, scattering their light into the world as innumerable sparks. These fragments of light are often hidden among the clay shards, held in bondage by the suffering and brokenness of the world. God then created human beings for the purpose of gathering up all the sparks of divine light scattered to the four corners of the earth. The good Jew is called to seek out and liberate the sparks of primordial light that bear God's presence in the world. To do so, is to pursue tikkun olam, "the repair or healing of the world."*

In this Kabbalist tradition, we find a powerful metaphor not only for faithful living but for creative photography. The metaphor suggests at least three things, the first about the object of our interest, the second about the impulse to create, and the third about the power of the beauty ingredient in resplendent light.

Photographic creativity is about searching out the delicate, scattered fragments of light that have already spilled into the world. This beauty is already there. You just have to find it. It's not in the eye of the beholder. It's in the nature of things. A photograph is a good one to the extent that it bears witness to those often overlooked but always given fragments of splendorous light already in the world. Photographs are invitations to liberate these sparks of light from bondage to the stale, habituated, hurried ways of seeing that conceal them from us.

But why do photographers search out these fragments of light? We do so not merely to make a beautiful image that pleases the viewer. We seek something deeper than the viewer's pleasure and approval. Photographs aim at a greater end, "the repair and healing of the world." Creativity is our attempt, often halting and always partial, to touch something real and outside of ourselves and to be healed by it. The creative gesture is also an invitation to others to touch it and be healed as well.

Artistic pursuit is thus not about a tortured artist expressing some fictional inner genius, inflicting the vagaries of her or his tumultuous inner life on the rest of us. Nor is it about creating pretty pieces to hang as ornaments on the wall above the sofa. Rather, the artistic pursuit of beauty reveals a longing for connectedness with the primordial light that is the source and end of all things. Creativity is at once the artist's own attempt and invitation for others to participate in the wholeness, restoration, and healing that lies at the heart of the world. To know the beauty of the light is to experience oneself as part of something much larger and infinitely more interesting than oneself. To experience such beauty, or better, to soak in it over time, is to live proleptically into wholeness, participating in the unifying power that creates, sustains, and directs all that is.

To experience the beauty made possible by resplendent light is both unsettling and liberating, troubling and reassuring. It is unsettling and troubling because having dwelt in its midst, we can no longer casually overlook the brokenness of our world that hides its sparks. We sense the unsettling dissonance between the fragments of light and all that conspires to conceal them. Contemplation flows into action, but an action that always returns again to the contemplation of the liberating, reassuring light that saturates all things.

-------------------------------

*http://www.tikkun.org/nextgen/how-the-ari-created-a-myth-and-transformed-judaism

For the Healing of the Nations

Amidst the Great Depression and rise of fascism in the 1930s, the French social documentary photographer, Henri Cartier-Bresson criticized Ansel Adams for neglecting to photograph the social crises of the day. "The world," he said, "is going to pieces, and Adams...[is] photographing rocks and trees."*

Cartier-Bresson was right about the world in the second quarter of the twentieth century. It was coming unraveled. The United States was in the depths of the Great Depression and staggering rates of unemployment, long soup lines, and widespread homelessness seemed overwhelming. Even the land was in exile, with its fertile topsoil carried off by the winds of the Dust Bowl. For many, the American dream seemed a lie, and it lost its mythic power over their imaginations.

Fascism was on the rise in Germany, Italy, and Japan, and a second world war seemed merely a matter of time. The Ku Klux Klan was at its height in the United States, and with it came unparalleled numbers of brutal lynchings and institutionalized racial violence. A good bit of Cartier-Bresson's own groundbreaking social documentary photography would depict this world governed by fear, violence, scarcity, social dislocation, and racial animus.

If Cartier-Bresson was right about the world, he was wrong about Adams. Adams was not insensitive to the social realities unfolding around him. He felt them keenly. But he kept on photographing rocks. "We need a little earth to stand on," Adams said, "and feel run through our fingers."* Adams knew that there was a deeper reality beneath the fears and immediate crises of the day, a deeper beauty resident in the natural world, and that contact with it was essential to human flourishing, essential to what the wild-eyed apocalypticist called "the healing of the nations."** Tempting as it was to turn his camera in service of social and political movements of the day, Adams kept it trained upon rocks, trees, lakes, and snowstorms because he knew that there was a healing power in natural beauty, a power that connected us with primordial goodness, hope, and receptivity to the mystery and giftedness of all things. To experience such beauty was to feel in one's gut the cosmic benevolent goodness disposed toward life, justice, and the harmonious existence of all beings.

Without the healing balm of beauty, the energy of social activism would flash bright but emit no heat. Or worse, it would get fused with the bitterness and blind self-righteousness that often imperil zealous do-gooders. To neglect this beauty was to neglect the ontological grounding of all being, even if this neglect clothed itself attractively in the immediate gratification that can come from social activism and art for a political cause. Adams knew that ethics needs metaphysics; that the pursuit of the True and the Good must always also be the pursuit of the Beautiful at the same time.

Adams's was not a call to an aesthetic escapism but rather to groundedness, to the cultivation of the soul, and to a connectedness with natural beauty that issues in life, joy, and gratitude. These experiences leave less room for the chronic anger, bitterness, and cynicism that threaten to engulf us in an age of violence, fear, and racism.

In our contemporary world so similar to the one described by Cartier-Bresson, we would do well to pause and linger with Adams's insight. His was not a call to quietism. He did, after all, photograph the Manzanar Internment Camp and the Japanese American citizens imprisoned there by racist fear masquerading as national security, and he released those photos into the public domain to express his moral outrage and elicit it from Americans. He was also a key figure in advancing the cause of early environmentalism, writing thousands of letters to politicians and editors of newspapers. But in the end, for Adams, the social world was grounded in the natural world, and we fail to see this at our spiritual peril.

Social activists, the victims of injustice and violence, and the morally indifferent must all look at the rocks from time to time. Out of the depths of their mysterious beauty might come the transforming grace that will rescue all of us from self-righteousness and alienation. Out of the rocks may come "the healing of the nations."

____________________

*Quoted in "Ansel Adams: A Documentary Film". Produced by Ric Burns in conjunction with PBS's American Experience Series. Transcript available at http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/amex/ansel/filmmore/pt.html.

**Revelation 22:2