The Allure of Film in the Digital Age

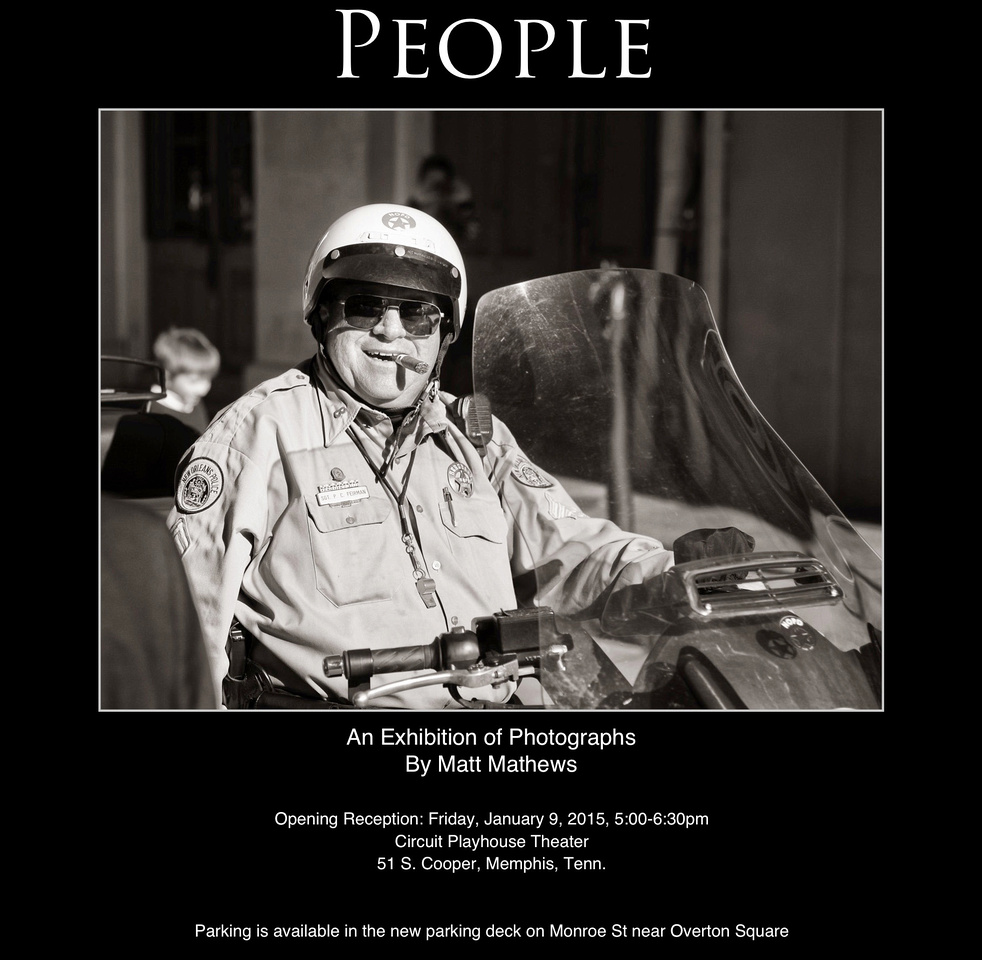

Invitation & Artist Statement for "People"

"We're born naked, and the rest is drag."

-- RuPaul, Drag Queen

Beauty, Cows, and Gnats

In Lawrence and Meg Kasden's 1991 film "Grand Canyon," there is a scene in which Mack, a wealthy lawyer, and Simon, a working class tow truck driver are discussing the Grand Canyon. Part of their exchange follows.

Simon: [sighs] When you sit on the edge of that thing, you just realize what a joke we people are. What big heads we got thinking that what we do is gonna matter all that much. Thinking our time here means diddly to those rocks. It's a split second we been here, the whole lot of us. And one of us? That's a piece of time too small to give a name.

Mack: You trying to cheer me up?

Simon: Yeah, those rocks are laughing at me, I could tell. Me and my worries, it's real humorous to that Grand Canyon. Hey, you know what I felt like? I felt like a gnat that lands on the ass of a cow that's chewing its cud next to the road that you ride by on at 70 miles an hour.

Mack: [laughs] Small.

We human beings often suffer from delusions of grandeur, assuming that we are the measure of all things. We labor under the illusion that our petty conflicts and triumphs are the metric of meaning in the universe. We imagine a world that exists solely for us, and we even refashion God into a cosmic sugar daddy who dotes over us, waiting to shower us with prosperity. But this small world with its even smaller god is an illusion.

It is very difficult to maintain this illusion when you sit on the edge of the Grand Canyon or hike in the deserts of the Southwest. In such places, we feel acutely our smallness and sense the landscape's inhospitality to human life. There is rarely water to drink. The sun scorches the skin. The wind drives fine dust into eyes and camera lenses. There is little shade. And then there are the rattlesnakes, scorpions, and tarantulas. Such places were not made for us. We are aliens in a foreign land. The God of this place is far more interested than we are in things other than us.

And yet, such wildness is terrifyingly beautiful. Such beauty transforms rather than entertains us. It tears loose our desperate, controlling grasp on ourselves and the world. It topples our little god. Such beauty dislocates us. Then it relocates us in a new world governed by a vast and different economy of meaning. It frees us to be gnats on a cow's ass as the cosmos goes speeding by at seventy miles per hour.

This belittling power of beauty is not the same as the petty belittling we do to one another as human beings. It does not erase our or another's humanity. To be small in a big world means that there's room for all. Beauty frees us to be fully, authentically human together.

Poet Muriel Rukeyser reminds us that "the universe is made of stories, not of atoms."* Beauty narrates a new story, a grand new epic with a new plot, new values, and new characters. Where we once worked anxiously to fit episodes of beauty into the big story of our lives, we now find that our lives are but small episodes in the grand epic of beauty that envelops them and all that is.

We are saved by smallness.

-------------------------------------

*Muriel Rukeyser, "The Speed of Darkness" (1968)

Deliverance from Temptation

Photography is my discipline for learning to be fully present to the world. When I take up the camera, I go exploring, tuning my senses to things that I might otherwise pass by in busyness and habit. It is an act of devotion to the real that frees me from constricted awareness and bondage to the illusions that so easily creep into daily life. It has taken quite awhile for me to arrive here, and along the way I have succumbed to a few temptations.

When I began photographing, I fell for the temptation of believing that there was a perfect camera, lens, or tripod which, if I found and bought it, would catapult my pedestrian photographs to greatness. And surely, there is a benefit to finding the right gear that suits your photographic style. To make good photographs, you need the right tools the same way a master woodworker needs the right tools to make great furniture. But camera gear does not make good photographs. Attentive photographers do.

I next fell for the temptation of believing that I could only make good photographs in exotic, picturesque places. I've walked along many miles of desert, forest, and beach, and I've made some good photographs along the way. To make good photographs, you regularly need the stimulation of new environments that evoke wonder, delight, and experimentation. But picturesque places do not make good photographs. Attentive photographers do.

And finally, I succumbed to the temptation of believing that strict adherence to rules of graphic design and composition would transform my photographs into great ones. So, I learned the rule of thirds, mastered the color wheel, faithfully sought out leading lines, and attuned myself to the siren song of the s-curve. And I learned that such design and compositional techniques do, in fact, enhance the visual poetics of my photographs. But such techniques do not make good photographs. Attentive photographers do.

Tools, travel, technique -- these are things that belong to what the ancient collection of Taoist writings known as the Chuang-tzu calls Little Understanding. Little Understanding is largely technical in nature and it is indispensable to creativity. But there's another kind of knowledge, the kind the Chuang-tzu calls Great Understanding. Great Understanding is creative vision born out of unconstricted attentiveness to one's environment. It is intuitive, unforced, spontaneous, and responsive to surprise. It is attuned to the mystery in the ordinary. Great Understanding involves heightened awareness of the evanescent and fleeting character of each moment of existence, and it lingers there, seeking not to own, possess, or control things. It lingers there to participate in and enjoy communion with things, but then lets them pass away as they inevitably must.*

I was reminded of the importance of Great Understanding again this week when I walked out to my car on the driveway. In the ten-second walk from my front door to the car, I was struck by the sullen, grey morning skies and the piles of leaves that the wind had blown into my front yard. I noticed the raindrops from early morning still on some of these leaves, and I was especially intrigued, for reasons I cannot fully explain, by the ginkgo leaves. And so, I reached for my camera and lost myself for an hour in the Great Understanding of the leaves.

Raindrops on a Ginkgo Leaf is one morning's triumph over old temptations and a savoring of Great Understanding.

-------------------

*I am indebted to Philippe L. Gross and S.I. Shapiro's The Tao of Photography: Seeing Beyond Seeing (Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2001; pp. 10-12) for this discussion of Little and Great Understanding.

R.I.P Yolanda

Last Saturday, I was combing the backroads of northwest Mississippi, looking for worthy photographs. This is the land of the Mississippi River Delta, and it is flat, low, fertile earth nourished over the years by the floodwaters of the Big Muddy. It is the land of King Cotton. It was once the land of slavery and unspeakable suffering. It is the land over which southern and northern troops moved during the Civil War. It is a land that bears the marks of its history in the still wide gap between black and white.

As I approached an intersection of two country roads, I spotted a roadside memorial to Yolanda, who died tragically in an automobile accident. Like most of us, I have seen many such roadside memorials, especially in the American Southwest where they are known as descansos, "resting places," and can be traced back to the centuries-old, Hispanic-American practice of marking the landscape with memorials wherever weary pallbearers briefly set down the casket on their long walking journey to the burial site.

I know virtually nothing about Yolanda, except that she died too young and died tragically on this little patch of flat and fertile land that has already known too much suffering in American history. I was moved by the austerity and simplicity of this handmade marker. The little angel figurine at the base of the cross has begun to dissolve and crumble in the elements. And with time, storms, and winds, the paint will fade and the wooden cross will fall over and disappear into the soil.

RIP Yolanda is someone's protest against private grief. It is a stubborn refusal to confine grief to the church, cemetery, or home. In a North American culture that denies death and often covers over its tragedy with embalming fluid, makeup, and tidy, otherworldly religion, RIP Yolanda takes us to the public place of senseless tragedy, the place where a particular young life was lost in a patch of dark Delta dirt. Set against the flat, wide, almost horizonless expanse is this place of particularized loss and grief, so poignant and intimate it goes only by a first name. Here is a public commingling of memory, sorrow, and warning to others traveling these isolated roads. If there is genuine redemption in this place, we struggle to find it.

What troubles us about RIP Yolanda is the lack of information surrounding it. We want to fill in the gaps, weaving together a possible biography and coherent account from a million loose threads of obscure clues and gross generalizations snatched up in a quick drive through of the nearby town. We speculate about the cause of the accident that killed her. We wonder if she or another party was to blame. We imagine speeding, drunk, sleepy, or preoccupied drivers. We want to sort out the sheep and the goats, the virtuous from the villains. We long for a morality tale that will provide an ersatz redemption for the whole damned thing. But none is given.

In the end, RIP Yolanda sets a question mark against all the easy exclamation points that punctuate our morality tales. And paradoxically, that may well be what redeems the tragedy, freeing Yolanda and us from easy answers, religious bromides, and morality tales too good to be true. Perhaps then, and only then, can we say with the ancient Hebrew writer, "Though God slay me, yet I live."

Making a Mountain "Look How it Feels"

In April 1927, Ansel Adams spent a day hiking up toward Half Dome in Yosemite. The trip was long and hard, and by the time he arrived at his final destination, he had only two unexposed glass plates left. Once at the Diving Board, a small rock protrusion below the face of Half Dome, he was overwhelmed by the beauty and immensity of the sheer granite wall towering over him. As he set up his view camera and readied it for the exposure, he realized that the photograph he was about to make would not communicate the experience of that moment. The photograph might faithfully duplicate the shapes, textures, and landscape, but it would not capture the experience of being overwhelmed by this massive monolith that in some ancient past had lost half its face in an apocalyptic crash of rock.

Adams later said that what he wanted was to "make it look how it felt." A straight exposure could not do that. So, Adams reached for his heavy red Wratten A filter, which dramatically darkened the surrounding sky and much of the face of the granite. This creative choice imparted drama and awakens in viewers a sense of the monolith's foreboding presence. The resulting photograph, Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, has a gothic and ominous quality that unsettles us even as it lures us. It retains this power despite the damage to the negative from the 1937 fire in Adam's darkroom that requires the prints to be cropped tightly at the top.

In early 2009, I was photographing in Yosemite during an early spring storm. I approached Half Dome and stood alone in the meadow beneath it, watching as the clouds drifted across it, sometimes revealing and other times concealing its surfaces and details. As I watched, gusts of wind lifted flurries of snow off its face and swirled them beautifully around the granite. Watching this primordial dance of granite, ice, clouds, and wind, I felt the mountain.

When we feel the mountain, we feel our own smallness. We are reminded that we are neither the measure nor the measurer of all things. We realize that we are measured by forces beyond ourselves, forces that both bear us up and bear down upon us. Such experiences deliver us from our exaggerated sense of our indispensability to the cosmos.

This sobering sense of our smallness opens the possibility of living more joyfully. It permits us to be creatures again unburdened by graceless perfectionism. It beckons us to embrace our fragility and limitations, and to love and be loved through them. It calls forth compassion for ourselves and all other creatures in the face of our and their partialities.

Storm over Half Dome asks you to feel the mountain.

Kairos, Chronos, and the Granite Dells

On Kinesthetic Knowledge

When as a child I watched my great grandmother knit, I was mesmerized by how quickly and instinctively her hands moved to make the delicate stitches of her sweaters. She did not think about or even look at each stitch. The stitches just flowed effortlessly from her hands as she talked to me. I remember those hands whenever I watch commercial fishermen filet their fish with the same kind of effortless, unthinking movements of hand and knife. And I remembered them again today when I watched the hands of the potter as she deftly and effortlessly turned a shapeless lump of clay into a bowl right before my very eyes.

Grandma's hands and those of the potter point to kinesthetic knowledge. Such knowledge is not of ideas or concepts. It's not of anything. It's instinctive know-how accumulated through hours of practice. It is an intuitive capacity for rhythmic movements and practiced gestures, all well-timed and economically executed in pursuit of a craft. Such knowledge is seated in the memory of muscles. We only acquire it through the movements themselves. Movements that begin as clumsy, slow, and awkward become skilled, quick, and graceful the more we do them. When the fingers meet the mud and clay, they just go to work, reflexively increasing and decreasing the pressure first here and then there, adjusting effortlessly to the texture and thickness of the clay as the wheel turns. Such knowledge is not linear, conceptual, or verbal; it's intuitive, reflexive, and somatic. It's fluidic improvisation. The Taoist speaks of it as wu wei, "effortless effort."

Potter's Hands reminds us that such kinesthetic knowledge is beautiful to witness. When mud-slathered fingers conjure form from a formless lump of clay, we are reminded of our own connectedness to earth and mud. We are brought back to elemental things, to the ancient, primordial awareness that we are enfleshed spirits most at home in earthy mud. Potter's Hands calls us back to our flesh and beckons our spirits to embrace it and conjure up some fresh beauty of our own.

The Lost Art of Beholding

We used to "behold" things. We don't anymore. Somewhere along the way, Behold fell out of our vocabulary and doing it from our practice. Etymologically, it derives from the Old English word bihaldan, which meant to "to give regard to," "to hold fast," or even "to belong to." Behold is an unfashionable word, but more to the point, it is an unfashionable practice in a culture dominated by the busy person's glance, the consumer's looking for, and the Pharisee's stare.

Beholding something requires that we offer it our total attention, that we allow ourselves to be captivated by it in wonder and awe. When we behold something, we encounter it as gift and mystery. When we behold things, they do not so much belong to us as we to them. Beholding things means lingering over them with a long, loving gaze, running our finger over the sharp edges of their beauty, and swaying to their silent melodies. When we behold, we participate in and even enjoy communion with what stands before us. And when we are done beholding, we release the butterfly that it might fly away.

We are often too busy to behold. The best we can muster is a glance. We pass our eyes over things casually and quickly. We give no regard, grant no honor, perceive no intrinsic value in the things at which we glance. We see casually, lacking mindfulness. In the hustle of modern life, we merely scan over things so we don't bump into them. The glance often grows in the soil of our exhaustion, habit, and apathy.

When we manage to move beyond the glance, it is often to the commodifying gaze of consumerism. This is the gaze of the shopper that looks twice, first at the thing, then at the price tag. This is seeing as looking for -- looking for a bargain, a sale, or a curio for the living room shelf. It is the kind of seeing that quantifies, calculates, compares, manages, commodifies, and, in the end, owns. Such seeing is not really a seeing of the world but a seeing of mere products.

More dangerous still is the Pharisee's stare which meets what stands before it with a condemnatory gaze that is at once disdainful toward but thrilled by the forbidden. When we stare, we reduce what stands before us to a freak that attracts us even as it is forbidden to us. When we stare, we see pornographically. We do not participate in communion with the deep goodness of what stands before us. Instead, we watch from the side, emotionally disconnected even as our bodies, in this case our eyes, are aroused. The freak entertains us but does not call forth from us empathy, only disdain tinged with titillation. Fear triumphs over love, objectification over communion, pity over solidarity, judgment over grace, voyeurism over participation.

Beholding is graced seeing. It is an act of love that not only releases what is seen from our grasp but enables us to release our grasp upon ourselves. Beholding changes us for the better. Glancing, looking for bargains, and staring do not. When we behold things we see their glory and splendor, and this gradually remakes us.

Behold, Magnolia Blossom, No. 1.

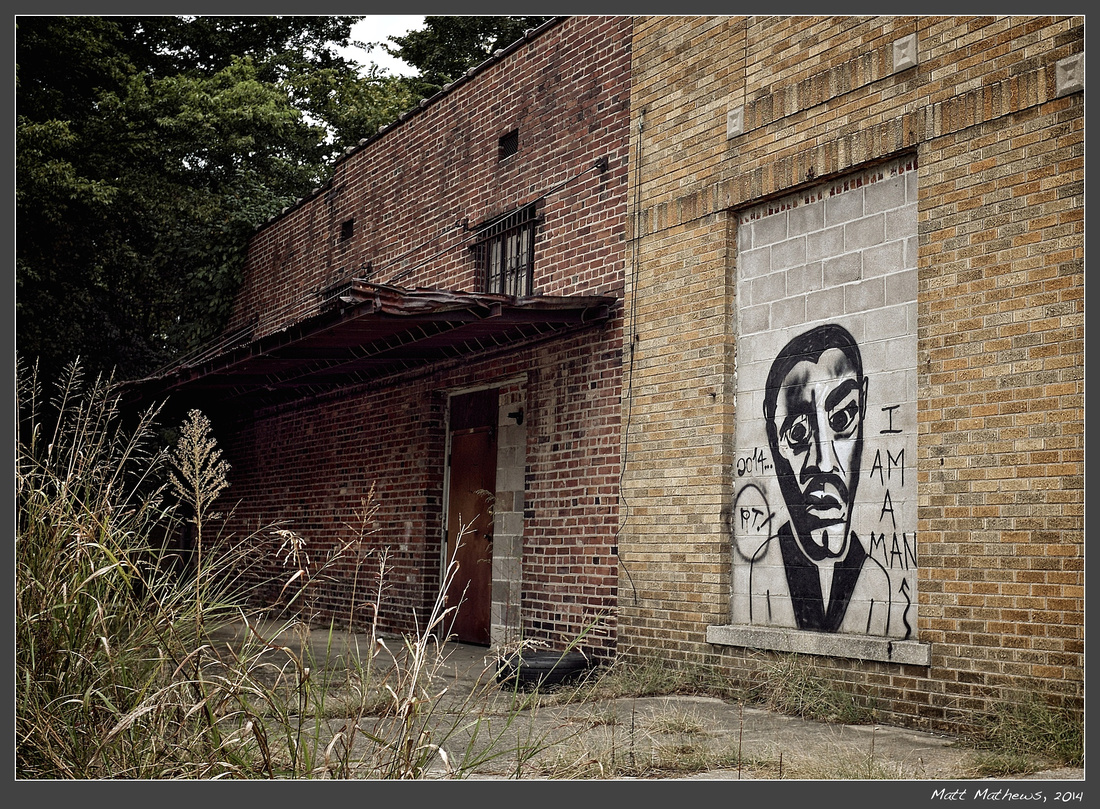

Sampling Ernest Withers's "I Am A Man"

Ode to Ernest Withers, 2014

I knew Ernest Withers's photographs long before I ever knew it was he who had made them. Withers (1922-2007) was a photographer based in Memphis, Tennessee who photographed celebrities. But most importantly, he was one of the premiere photographer of the Civil Rights Movement. Withers's images are for the Civil Rights Movement what Matthew Brady's images are for the Civil War, what Ansel Adams's are for Yosemite, or Dorothea Lange's are for the Great Depression. Withers enjoyed unparalleled access to Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders, and he knew well the power of photography to strike at the American conscience and exert moral suasion. If King was the preacher, the wordsmith who moved a nation, then Withers was the seer whose photographs cast in silver tones the concrete, deeply intimate nature of the struggle as felt by African Americans.

Withers's photographic corpus of the Civil Rights Movement is very large, and in photograph and photograph we see a master of composition, timing, and exposure. In an age in which cameras often lacked light meters and lenses had to be focused manually, Withers always managed to get the iconic photograph. His technical abilities, though, were in service of a deeper vision. While his vision included photographing the large scale events of the movement, his brilliance, in my judgment, lay in his capacity to depict the struggle as it played out on a very intimate, human scale. Many of his images concentrated the struggle in a single individual or small group of people, often keenly focused on body language and facial expression amidst the palpable absurdities of daily life in a segregated society. We see these motifs in his Martin Luther King Resting on a Bed and in No White People Allowed in Memphis Zoo Today; or in one of my favorites, Father with Daughter in Stroller (1961).*

But Withers's most famous photograph is I Am a Man (1968). This photograph depicts the sanitation workers gathered outside Clayborn Temple on the corner of Hernando Street and Linden Avenue (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard) in downtown Memphis preparing to march. Few photographs express with such poignancy the personal as well as political nature of the movement. This was no mere political movements for rights, power, and equality; it was a spiritual movement demanding full personhood, and yes, even full manhood in the over-"boyed," segregated South.

This past Sunday, I went down to Clayborn Temple, now a boarded-up, for-sale shell of a building. It was often here that King delivered his speeches, huddled with his inner circle of leaders to plan strategy, and it was on this corner where the marchers gathered to begin their protests. It is sad to see this old African Methodist Episcopal Church building in such a state of decay. I went looking for a photograph but came away with none. It was a disappointing photographic outing.

As I left Clayborn Temple, I drove east on Vance Avenue, and several blocks up from the church I saw the scene depicted in my Ode to Ernest Withers, 2014. It took a moment to realize what I was seeing. When I did, I drove around the block for a second look. This time, I stopped and made the photograph, sensing acutely the connection between this bit of graffiti on the wall of a unimpressive vacant building and Withers's I Am a Man, made forty-six years earlier just a few blocks away. My photograph samples the lyrics of I Am a Man, but it does so at secondhand. I am after all merely sampling the lyrics of the graffiti artist who first sampled Withers's lyrical I Am a Man.

This sampling, of course, bears witness to the ongoing power of Withers's initial image. In I Am a Man, we feel the Civil Rights Movement. We see that while it was about rights, power, and equality, it was also about asserting, celebrating, and embracing one's own somebodyness in a world that daily tried (and tries) to erase you into nobodyness. It is here that we can see that before the Civil Rights Movement was a political movement, it was a spiritual movement born out of the Black Church and borne along by it.

When secular historians are tempted to overlook this fact, analyzing the movement only as a series of well-played political stratagems, we have the witness of Ernest Withers and a graffiti artist to lead the protest. Before Withers or the sanitation workers were "political players," they were "men."

*These titles of the photographs were not assigned by Withers; I have simply created them for purposes of this post.

Photographing Things "For What They Are and for What Else They Are"

The great mystically minded photographer Minor White claimed that "one should not only photograph things for what they are but for what else they are."

Photographs invite us to see the ordinary things of everyday life in a fresh way. They can be arresting, stopping us in our tracks. They disrupt our routine, casual ways of seeing and being present to the world. Something as simple and common as a strand of seaweed floating aimlessly in dark water beneath a dock suddenly appears as something quite beautiful. And for a brief spell at least, it's hard to go back to seeing seaweed the same old way we always do. Part of the power of photography as a medium is its faithful, unforgiving, relentless depiction of the things as they are. There is a clinical exactness to the medium not commonly found in other art forms. This clinical exactness draws us more deeply into the thing, inviting us to see details in it that we might otherwise overlook. A photograph connects us to a thing in its unrepeatable particularity. Kelp, No. 2 is not about seaweed in general; it is about this strand of seaweed floating in this water at this moment bathed in this quality of light.

And yet, Kelp, No. 2 is about more than this particular strand of kelp. It is a study of lines and curves, of subtle gradations of tone that create depth and dimension, and of textures set against a glassy smooth background. Here, I think, is the "something more" to which White was referring. These lines, curves, tones, and textures bear witness to the deep structures of being itself. They touch the metaphysical beneath but always manifested in the physical. Ours is a world expressive of order, of an underlying purposiveness. Ours is a world of rhythms, harmonies, and creative dissonances. When we experience these dimensions of a beautiful thing, we are experiencing something objectively real about the world. When we experience this it evokes something powerful in us. It evokes a sense of rightness and well-being. We sense that the world in which we live is not a cosmic accident governed by fortune and chaos. We sense that this world is right, that it is as it should be, and that there is a place within it for us to flourish. And while ours certainly is not the central place, it is nonetheless a good place where the forces that bear us up in grace, hope, and love are ultimately greater than those that bear down upon us in tragedy, evil, and suffering.

When experiences of beauty attune us to a sense of cosmic rightness and well-being, they ultimately anchor us as moral selves. Before we can sense injustice, be angered by unfairness, or commit ourselves to a moral cause, we must first sense dissonance -- the dissonance between how things are and how the cosmos intends them to be. Experiences of beauty thus assure us, often more affectively than cognitively, that "the moral arc of the universe is long but bends toward justice" (Martin Luther King, Jr.). It is only out of this felt experience that moral motivation and commitment emerge or are sustained over time. When our pursuit of the good is disconnected from our pursuit of the beautiful, the moral life becomes the merely moralistic life that soon withers and dies from lack of spiritual nourishment. We need to sense that our moral strivings are not simply our moral strivings but participate in a deeper ontological force that exerts a persistent momentum toward cosmic rightness and the well-being of all creatures.

In the end, seeing a little seaweed from time to time may well rescue us from self-righteous, self-serving do-goodism.

The Gift of a Second Chance

Mr. Ellis Reading the Newspaper

Mr. Ellis Reading the Newspaper

In the years that I have been photographing seriously, I have rarely had a second chance to correct a serious creative error. This week, I got such a chance.

In 2009, I had the honor of photographing inside The Ellis and Sons Iron Works located on the corner of Front Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard in Memphis, Tennessee. Ellis and Sons is among the oldest, continuously operated businesses in Memphis, and despite profound economic shifts that have severely diminished the business, it survives. In 2009, I enjoyed spending a few hours inside the foundry, photographing the massive machinery and interesting textures, lines, and shapes that fill this old warehouse. I remember that around every turn in this old building were so many interesting things to photography that it felt overwhelming. Among the favorite photographs that I made that day in 2009 is this one of a piece of machinery used to melt metals for casting into molds.

My mistake in 2009 was failing to photograph Mr. William Ellis himself, the namesake and direct descendent of the founder of the business. I met Mr. Ellis that day, already then in or fast approaching his nineties, and he was among the most gracious and proud men that I have met. He has worked in this same factory since he was a fourteen-year-old boy. He toured me around the shop, telling me of the history of this family-owned business that an earlier Mr. William Ellis established in 1862 to cater to the boats carrying freight on the Mississippi River, one block west of the foundry. Mr. Ellis then gave me free rein to wander through his shop unattended. And yet, I never turned my camera to Mr. Ellis himself. I have regretted this oversight every time I review the collection of photographs of the industrial forms I made that day.

Today, I atoned for my creative sin. While walking in the South Main District of Memphis during the late morning hours, I wandered past the Ellis and Sons Iron Works building. As I did, my mind went back to 2009 and my failure to photograph Mr. Ellis. And suddenly, there he was, visible through a dirty old window of the foundry, surrounded by piles of newspaper and equipment and framed by reflections cast in the window. There he sat in soft midmorning light reading the newspaper as he probably does every day. And he did not see me.

First I photographed him from the front to reveal his face; and then it struck me that a far subtler photograph was to be had if I photographed over his shoulder, and just as I moved into position, he lifted his left arm and rested his hand on his neck. When I made the exposure, I knew immediately that I had the photograph that I have longed for for five years.

After I made the photograph, I considered going inside to ask if I might photograph him formally. For a moment, I worried about the clutter surrounding him in the portrait and thought a photograph made inside would be "cleaner." But then I realized that this clutter has surrounded him for the eighty years that he's worked in this building, and it is part of what defines him. So, I did not go inside. I knew that I had the photograph that I wanted. But more importantly, it seemed that going in and interrupting him would diminish the extraordinary manifested in this most ordinary of moments.

Photographers rarely get second chances, but on this day I did. And I am deeply grateful for having been in the right place at the right time.

Cheers, Mr. Ellis. Carry on with your daily routine. And thank you for a moment in which the ordinary was suddenly bathed in the extraordinary.