Photographs as Metaphors

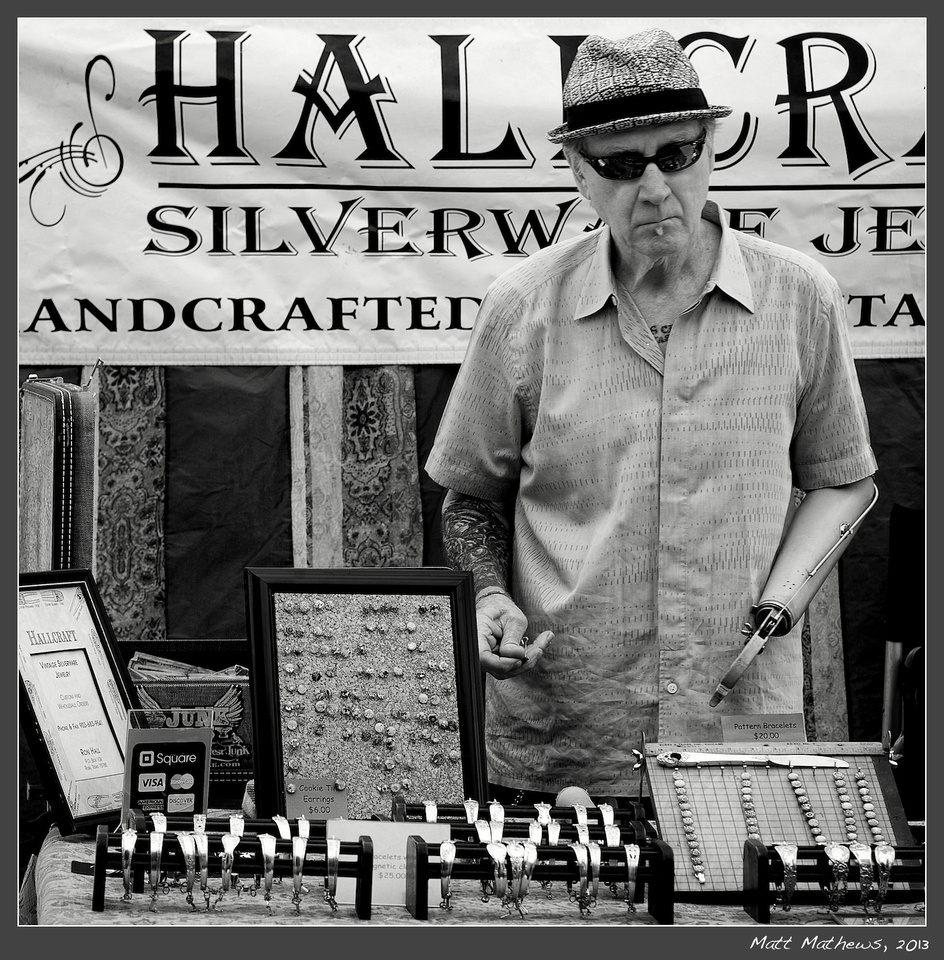

Jewelry Craftsman, Clarksdale, Mississippi, 2013

I have come to believe that the art form most similar to photography is poetry. The poet aims for an economy of words, subtracting all extraneous ones in the pursuit of highly concentrated meaning. Photographers do the same. We seek to concentrate meaning by the subtraction of all elements in a scene that might dilute it. And like the poet, we must embrace inherited forms for our creativity. Just as with the poet who chooses to write a haiku or sonnet, the photographer chooses to work within inherited structures, aesthetic forms, and visual traditions that place constraints on the creative act. Such constraints, however, far from stifling creativity, call it forth. And finally, like poets, photographers use rhyme schemes. Photographs hold our attention quite often because their visual elements curiously echo one another, creating a pleasing visual rhyme. In Jewelry Craftsman, for example, we might notice that the craftsman holds in his right hand a clip that faintly echos the end of his prosthesis. Or again, as we look a bit longer, we might notice the rhyme between the missing letter of "Handcrafted" and the craftsman's missing hand.

But most importantly, poems and photographs traffic in metaphors. Etymologically, metaphor is interesting. Metaphorein in Greek literally means "to carry over" or to "carry beyond," and here is a curious thing. Metaphors carry us over a gap between two worlds of meaning. And yet, in carrying us over, there remains an elusive beyondness to the new land of meaning that prevents us from fully occupying and domesticating it. Metaphors bring into view a great beyond, and they tease us by letting us visit and even touch it briefly but never own, possess, or fully control it. Metaphors, to borrow a phrase from the Hungarian photographer Brassai, "suggest rather than insist."

The late French philosopher Paul Ricoeur famously spoke of metaphors as having "a surplus of meaning," by which he meant that metaphors can never be fully translated into straightforward pedestrian prose without losing something in translation. When explanatory prose reaches out to grasp the meaning that metaphor throws out in front of us, its reach is never quite long enough. The metaphor eludes conceptual mastery, insisting on an element of indeterminacy and openness beyond exhaustive translation. This playful surplus of meaning is what holds our imagination even as it confounds the reductive impulses of the the mind. We get tangled up in metaphors, and in their bondage we find freedom and delight. In the swirling world of the metaphor, we touch levels of cognitive and affective meaning in ourselves and in the world that have hitherto eluded us.

Jewelry Craftsman is a visual metaphor. When I look at it, I am confronted by the fragility of human existence, by the power of beauty to embrace loss, tragedy, and brokenness in an act of redemptive transfiguration. I am confronted with the constant interplay of the organic and mechanical in modern life. I am reminded that much of life has an improvisational character where we must learn to make our jewelry with what's left over. Jewelry Craftsman throws out in front of us the tangle of our own loss and triumph, our own stubborn knots of brokenness, creativity, and new possibilility.

But look again at Jewelry Craftsman. It is at once less and more than all this. My hope is that it's worth more than a thousand words.

Voyeurism, Solidarity, and Queering the Camera

On Saturday, September 27, I attended the Midsouth Pride Festival and Parade in Memphis, Tennessee. This is my fourth time at this festival, and only now am I beginning to grasp more fully what it's all about.

Pride festivals and parades are about many things: celebration and defiance, excess and performance, sexuality and spirituality, costumes and authenticity, liberation and justice.

When one photographs at a Pride event, one can approach the task as either a voyeur or participant. I choose to be the latter. I seek to enter fully into the festival, and more importantly into the broader struggle of LGBTQ people. Participation is an act of solidarity rather than charity. Charity is merely the momentary, guilty conscience of the voyeur.

The way of solidarity involves forming deep, abiding friendships with LGBTQ people and other allies, nourishing and being nourished by a shared life that both transcends and includes the multitude of ways we are different from one another. It means coming alongside a marginalized but triumphant people, not as a self-appointed straight liberal savior, but as an empathetic friend who shares the burdens, the struggles, the victories, the defeats, the joys and laughter, the anger and pain. Solidarity means sticking around and finding your own life only when you lose it in the lives of others.

One of the gifts of solidarity is authenticity, and in the case of solidarity with my LGBTQ friends, it is an authenticity that regularly calls me forth from my own closets filled with false identities that are safe and comfortable. While the closets of LGBTQ people are often especially dark ones filled with toxic air that suffocates the spirit, most of us have closets of our own where we retreat and trade authenticity and flourishing for various false selves hell-bent on mere survival and unreflective social conformity.

When I photograph Pride events, it is a gesture of thanks and admiration to the LGBTQ community and its allies for empowering me to transgress with queer courage and drag-queen delight all those carefully guarded, arbitrary boundaries that masquerade falsely as natural and essential to my and society's wellbeing. My LGBTQ friends make me a better photographer and theologian, and in the end a better human being.

And it is to these friends that I say "thank you" with these 43 photographs. If you would prefer to see the photographs in the gallery or if your internet connection does not permit uninterrupted viewing of the slideshow below, click here.

Beauty, Whole and Broken

My exhibition of photographs, "Beauty, Whole and Broken" is on display in Founders Hall, Memphis Theological Seminary through December 10, 2014. The Artist Statement and a slideshow of the exhibited photographs appear below.

Artist Statement

“We should not merely run [our eyes] over [creatures] cursorily, and, so to speak, with a fleeting glance; but we should ponder them at length, turn them over in our minds seriously and faithfully, and recollect them repeatedly."

-John Calvin, Institutes 1.14.21

“Beauty, catch me on your tongue.”

-Andrea Gibson, “Birthday”

Faith is deliciously sensuous. It calls forth from us a long, loving look at the extravagant beauty of the world. Faith brings mindful seeing, a renewed attentiveness to the handiwork of God all around us. In faith, we are invited to attend to things small and large, fragile and threatening, with patience, delight, and awe. We are summoned to linger over particulars with heightened sensitivity and an expectation of surprise. Faith transfigures our casual seeing into the wonder-filled, wide-eyed gaze of a child. For Calvin, such seeing is an expression of gratitude, and when we fail at it, he judges us of guilty of "criminal apathy."

"Beauty, Whole and Broken" is a collection of photographs that invites us to acquit ourselves of the crime. These photographs celebrate two kinds of beauty. The first is whole beauty -- the beauty of pristine things free of defect and flaw. Such beauty is of things untouched by fallen human hands and free of tragedy, flaw, or brokenness. We see such beauty in the luminous blossoms of the dogwood, in a strand of seaweed floating aimlessly in dark waters, and in a moonrise over granite dells so strange in shape that we might mistake them for an alien world. To taste whole beauty is to taste the original goodness of God and the world and to be reminded that even though ours is but a small place in the world, it is a good place.

But even whole beauty gets broken. Wildfires ravage pristine landscapes. Here is another kind of beauty -- broken beauty. This is an improvised beauty that embraces tragic or flawed elements and transfigures them into something higher. We glimpse such beauty in the one-armed craftsman of hand-made jewelry whose hand holds a clip that echos his prosthesis. We see this beauty in the bliss of a boy riding a mechanical bull whose missing horn imperils the illusion. We see it in the bluesmen whose notes and voices squeeze beauty out of the depths of human suffering and anguish. To taste broken beauty is to taste redemption and to be reminded that God's beauty travels through the tragic rather than around it.

O Divine Beauty, "catch [us] on your tongue."

Why Black and White Photography?

Viewers of my photographs sometimes ask why I work in black & white more often than color. So let me offer an answer.

Black and white photography is abstraction. It relies on tonality, texture, and line to direct the viewer to what is essential in what is photographed. In suspending color, it asks something of the viewer. It asks you to work at seeing.

Black and white photography was born of necessity. It was the only medium available for the first hundred years after the first photograph was made in the late 1830's. But what was born of necessity has now become a choice for many photographers, myself included.

The choice to work in the black and white tradition is not unlike the choice of the poet who chooses to write poetry in the inherited forms of a haiku or sonnet when free verse is readily available. Like the haiku or sonnet, black and white photography brings a set of rules and formal structures that must govern the visual poetics of a picture. The photographer, like the poet, must embrace these rules and formal structures and regard them not as restrictions on creativity but as necessary conditions for it.

Black and white photography takes us back to elemental things. It invites the viewer to see the beauty of the weathered texture of the sunlit surfaces, the sculpturesque lines of the keel, and the elegant curves of the mooring ropes of a simple fishing boat.

Black and white photography is also a declaration that the photograph is an interpretation rather than a mere duplication of the world in front of the camera. Yet in its falsification, it speaks its own truth about the world.

I photograph in black and white because I want to see the world as it really is.

Edward Weston, California, and What's Worth Photographing

The great photographer Edward Weston once remarked that "everything worth photographing is in California." He was wrong, of course, and I believe he knew it when he said it. Weston casts a long shadow across twentieth-century photographic history. He was a mentor to Ansel Adams and founding member of the F/64 Group of west coast photographers most famous for their rejection of the movement of pictorialism that had prevailed in photographic circles at the turn of the twentieth century. Pictorialism sought to legitimate photography as an art form by imitating the aesthetic standards of painting. Held in suspicion for creating their images with a machine, pictorialist photographers sought to conceal the incriminating characteristics of a photograph by making it look like a painting. They smeared substances on their lenses to impart a soft, dreamy quality to their photographs; they printed on textured papers and smudged and scratched elements of the image to suggest the brushstrokes or textures of the paintbrush; and they often chose "classical," highly idealized, posed subjects that were intended to call to mind by way of allegory the eternal ideas, timeless values, common tropes of western art and civilization. All this was aimed at earning photography standing in the world of fine art.

Weston, Adams, and the members of the F/64 Group ultimately came to reject pictorialism because it was photography done with a bad conscience and because it sought to conceal the most powerful virtues of the photographic medium: its "straight" representation of the world as given to us rather than as idealized or modified by the human imagination. The camera rendered the world without artifice, and photography would have to stand on its own aesthetic merits. Led by Weston, "straight photograhers" embraced glossy, smooth photographic papers most unlike the textured or tinted papers of painters. They set the apertures of their view cameras to F/64, the smallest available aperture, which ensured that everything in the image was in sharp focus. Initially, Weston minimized his manipulations in the darkroom and refused to produce enlargements, favoring only 8"x10" contact prints to preserve maximum fidelity in tone, texture, and detail in the subject photographed. And perhaps most importantly, he turned his attention to form -- to the power of lines, curves, and tonal gradations in ordinary subjects all around him. His photographs were not to be allegories of otherworldly truths but celebrations of this-worldly beauty conveyed in the ordinary. They were a paeon to form, texture, and tonality sung in the voice of a new, "modern" aesthetic.

Weston refined his artistic sensibilities and techniques along the coast of California, with much of his work coming from Point Lobos not far from his home, Wild Cat Hill, on the Monterey Penninsula. As with Adams but to a lesser degree, California was a place of wildness and untamed beauty, and the rugged, unforgiving coastline was not subject to human artifice. If Adams celebrated the beauty of the Sierra, Weston celebrated the beauty of the coastline.

When I look at my Tidal Flow, Morro Strand State Beach, No. 2, I realize how growing up in the Central San Joaquin Valley of California positioned me geographically and artistically between Adam's Sierra and Weston's coastline. The more I photograph, the more aware I am that no one creates in a vacuum. We always create from within visual and aesthetic traditions whether we realize it or not. With the straight photographers, I value the world as it presents itself. The camera must be accommodated to the givenness of the world. My preference for black and white images belies my fascination with form, texture, and lines. I do not subscribe to the artist-as-genius fiction which assumes that artistic skill is an unlearned, native-born gift or burden that the artist is entitled to inflict upon the world. Photographs should not be about the inner life of the photographer; few things could be so boring. Photographs point in fleeting, halting, and partial ways to the beauty of the world. They are in invitation into the real beauty "out there" (in California and well beyond!). Beauty is not in the eye of the beholder; it is the metaphysical substratum of all that is. The question is whether we will pause to experience it.