Kairos, Chronos, and the Granite Dells

On Kinesthetic Knowledge

When as a child I watched my great grandmother knit, I was mesmerized by how quickly and instinctively her hands moved to make the delicate stitches of her sweaters. She did not think about or even look at each stitch. The stitches just flowed effortlessly from her hands as she talked to me. I remember those hands whenever I watch commercial fishermen filet their fish with the same kind of effortless, unthinking movements of hand and knife. And I remembered them again today when I watched the hands of the potter as she deftly and effortlessly turned a shapeless lump of clay into a bowl right before my very eyes.

Grandma's hands and those of the potter point to kinesthetic knowledge. Such knowledge is not of ideas or concepts. It's not of anything. It's instinctive know-how accumulated through hours of practice. It is an intuitive capacity for rhythmic movements and practiced gestures, all well-timed and economically executed in pursuit of a craft. Such knowledge is seated in the memory of muscles. We only acquire it through the movements themselves. Movements that begin as clumsy, slow, and awkward become skilled, quick, and graceful the more we do them. When the fingers meet the mud and clay, they just go to work, reflexively increasing and decreasing the pressure first here and then there, adjusting effortlessly to the texture and thickness of the clay as the wheel turns. Such knowledge is not linear, conceptual, or verbal; it's intuitive, reflexive, and somatic. It's fluidic improvisation. The Taoist speaks of it as wu wei, "effortless effort."

Potter's Hands reminds us that such kinesthetic knowledge is beautiful to witness. When mud-slathered fingers conjure form from a formless lump of clay, we are reminded of our own connectedness to earth and mud. We are brought back to elemental things, to the ancient, primordial awareness that we are enfleshed spirits most at home in earthy mud. Potter's Hands calls us back to our flesh and beckons our spirits to embrace it and conjure up some fresh beauty of our own.

The Lost Art of Beholding

We used to "behold" things. We don't anymore. Somewhere along the way, Behold fell out of our vocabulary and doing it from our practice. Etymologically, it derives from the Old English word bihaldan, which meant to "to give regard to," "to hold fast," or even "to belong to." Behold is an unfashionable word, but more to the point, it is an unfashionable practice in a culture dominated by the busy person's glance, the consumer's looking for, and the Pharisee's stare.

Beholding something requires that we offer it our total attention, that we allow ourselves to be captivated by it in wonder and awe. When we behold something, we encounter it as gift and mystery. When we behold things, they do not so much belong to us as we to them. Beholding things means lingering over them with a long, loving gaze, running our finger over the sharp edges of their beauty, and swaying to their silent melodies. When we behold, we participate in and even enjoy communion with what stands before us. And when we are done beholding, we release the butterfly that it might fly away.

We are often too busy to behold. The best we can muster is a glance. We pass our eyes over things casually and quickly. We give no regard, grant no honor, perceive no intrinsic value in the things at which we glance. We see casually, lacking mindfulness. In the hustle of modern life, we merely scan over things so we don't bump into them. The glance often grows in the soil of our exhaustion, habit, and apathy.

When we manage to move beyond the glance, it is often to the commodifying gaze of consumerism. This is the gaze of the shopper that looks twice, first at the thing, then at the price tag. This is seeing as looking for -- looking for a bargain, a sale, or a curio for the living room shelf. It is the kind of seeing that quantifies, calculates, compares, manages, commodifies, and, in the end, owns. Such seeing is not really a seeing of the world but a seeing of mere products.

More dangerous still is the Pharisee's stare which meets what stands before it with a condemnatory gaze that is at once disdainful toward but thrilled by the forbidden. When we stare, we reduce what stands before us to a freak that attracts us even as it is forbidden to us. When we stare, we see pornographically. We do not participate in communion with the deep goodness of what stands before us. Instead, we watch from the side, emotionally disconnected even as our bodies, in this case our eyes, are aroused. The freak entertains us but does not call forth from us empathy, only disdain tinged with titillation. Fear triumphs over love, objectification over communion, pity over solidarity, judgment over grace, voyeurism over participation.

Beholding is graced seeing. It is an act of love that not only releases what is seen from our grasp but enables us to release our grasp upon ourselves. Beholding changes us for the better. Glancing, looking for bargains, and staring do not. When we behold things we see their glory and splendor, and this gradually remakes us.

Behold, Magnolia Blossom, No. 1.

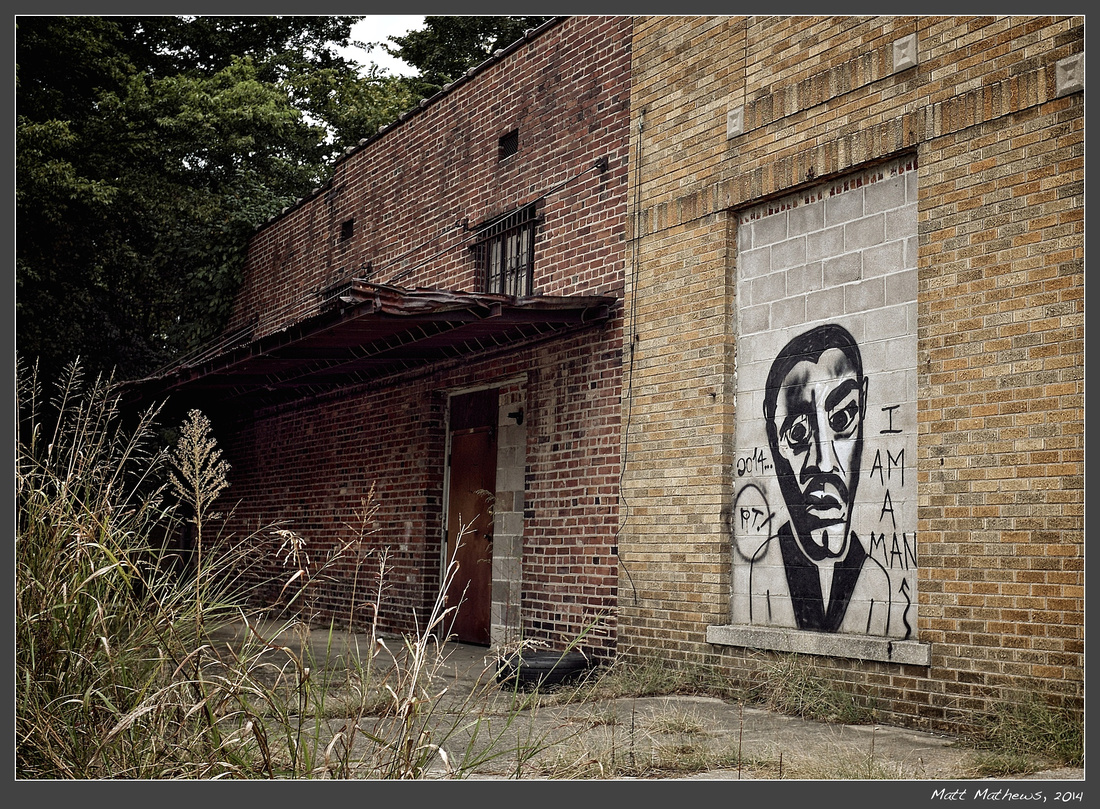

Sampling Ernest Withers's "I Am A Man"

Ode to Ernest Withers, 2014

I knew Ernest Withers's photographs long before I ever knew it was he who had made them. Withers (1922-2007) was a photographer based in Memphis, Tennessee who photographed celebrities. But most importantly, he was one of the premiere photographer of the Civil Rights Movement. Withers's images are for the Civil Rights Movement what Matthew Brady's images are for the Civil War, what Ansel Adams's are for Yosemite, or Dorothea Lange's are for the Great Depression. Withers enjoyed unparalleled access to Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders, and he knew well the power of photography to strike at the American conscience and exert moral suasion. If King was the preacher, the wordsmith who moved a nation, then Withers was the seer whose photographs cast in silver tones the concrete, deeply intimate nature of the struggle as felt by African Americans.

Withers's photographic corpus of the Civil Rights Movement is very large, and in photograph and photograph we see a master of composition, timing, and exposure. In an age in which cameras often lacked light meters and lenses had to be focused manually, Withers always managed to get the iconic photograph. His technical abilities, though, were in service of a deeper vision. While his vision included photographing the large scale events of the movement, his brilliance, in my judgment, lay in his capacity to depict the struggle as it played out on a very intimate, human scale. Many of his images concentrated the struggle in a single individual or small group of people, often keenly focused on body language and facial expression amidst the palpable absurdities of daily life in a segregated society. We see these motifs in his Martin Luther King Resting on a Bed and in No White People Allowed in Memphis Zoo Today; or in one of my favorites, Father with Daughter in Stroller (1961).*

But Withers's most famous photograph is I Am a Man (1968). This photograph depicts the sanitation workers gathered outside Clayborn Temple on the corner of Hernando Street and Linden Avenue (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard) in downtown Memphis preparing to march. Few photographs express with such poignancy the personal as well as political nature of the movement. This was no mere political movements for rights, power, and equality; it was a spiritual movement demanding full personhood, and yes, even full manhood in the over-"boyed," segregated South.

This past Sunday, I went down to Clayborn Temple, now a boarded-up, for-sale shell of a building. It was often here that King delivered his speeches, huddled with his inner circle of leaders to plan strategy, and it was on this corner where the marchers gathered to begin their protests. It is sad to see this old African Methodist Episcopal Church building in such a state of decay. I went looking for a photograph but came away with none. It was a disappointing photographic outing.

As I left Clayborn Temple, I drove east on Vance Avenue, and several blocks up from the church I saw the scene depicted in my Ode to Ernest Withers, 2014. It took a moment to realize what I was seeing. When I did, I drove around the block for a second look. This time, I stopped and made the photograph, sensing acutely the connection between this bit of graffiti on the wall of a unimpressive vacant building and Withers's I Am a Man, made forty-six years earlier just a few blocks away. My photograph samples the lyrics of I Am a Man, but it does so at secondhand. I am after all merely sampling the lyrics of the graffiti artist who first sampled Withers's lyrical I Am a Man.

This sampling, of course, bears witness to the ongoing power of Withers's initial image. In I Am a Man, we feel the Civil Rights Movement. We see that while it was about rights, power, and equality, it was also about asserting, celebrating, and embracing one's own somebodyness in a world that daily tried (and tries) to erase you into nobodyness. It is here that we can see that before the Civil Rights Movement was a political movement, it was a spiritual movement born out of the Black Church and borne along by it.

When secular historians are tempted to overlook this fact, analyzing the movement only as a series of well-played political stratagems, we have the witness of Ernest Withers and a graffiti artist to lead the protest. Before Withers or the sanitation workers were "political players," they were "men."

*These titles of the photographs were not assigned by Withers; I have simply created them for purposes of this post.

Photographing Things "For What They Are and for What Else They Are"

The great mystically minded photographer Minor White claimed that "one should not only photograph things for what they are but for what else they are."

Photographs invite us to see the ordinary things of everyday life in a fresh way. They can be arresting, stopping us in our tracks. They disrupt our routine, casual ways of seeing and being present to the world. Something as simple and common as a strand of seaweed floating aimlessly in dark water beneath a dock suddenly appears as something quite beautiful. And for a brief spell at least, it's hard to go back to seeing seaweed the same old way we always do. Part of the power of photography as a medium is its faithful, unforgiving, relentless depiction of the things as they are. There is a clinical exactness to the medium not commonly found in other art forms. This clinical exactness draws us more deeply into the thing, inviting us to see details in it that we might otherwise overlook. A photograph connects us to a thing in its unrepeatable particularity. Kelp, No. 2 is not about seaweed in general; it is about this strand of seaweed floating in this water at this moment bathed in this quality of light.

And yet, Kelp, No. 2 is about more than this particular strand of kelp. It is a study of lines and curves, of subtle gradations of tone that create depth and dimension, and of textures set against a glassy smooth background. Here, I think, is the "something more" to which White was referring. These lines, curves, tones, and textures bear witness to the deep structures of being itself. They touch the metaphysical beneath but always manifested in the physical. Ours is a world expressive of order, of an underlying purposiveness. Ours is a world of rhythms, harmonies, and creative dissonances. When we experience these dimensions of a beautiful thing, we are experiencing something objectively real about the world. When we experience this it evokes something powerful in us. It evokes a sense of rightness and well-being. We sense that the world in which we live is not a cosmic accident governed by fortune and chaos. We sense that this world is right, that it is as it should be, and that there is a place within it for us to flourish. And while ours certainly is not the central place, it is nonetheless a good place where the forces that bear us up in grace, hope, and love are ultimately greater than those that bear down upon us in tragedy, evil, and suffering.

When experiences of beauty attune us to a sense of cosmic rightness and well-being, they ultimately anchor us as moral selves. Before we can sense injustice, be angered by unfairness, or commit ourselves to a moral cause, we must first sense dissonance -- the dissonance between how things are and how the cosmos intends them to be. Experiences of beauty thus assure us, often more affectively than cognitively, that "the moral arc of the universe is long but bends toward justice" (Martin Luther King, Jr.). It is only out of this felt experience that moral motivation and commitment emerge or are sustained over time. When our pursuit of the good is disconnected from our pursuit of the beautiful, the moral life becomes the merely moralistic life that soon withers and dies from lack of spiritual nourishment. We need to sense that our moral strivings are not simply our moral strivings but participate in a deeper ontological force that exerts a persistent momentum toward cosmic rightness and the well-being of all creatures.

In the end, seeing a little seaweed from time to time may well rescue us from self-righteous, self-serving do-goodism.

The Gift of a Second Chance

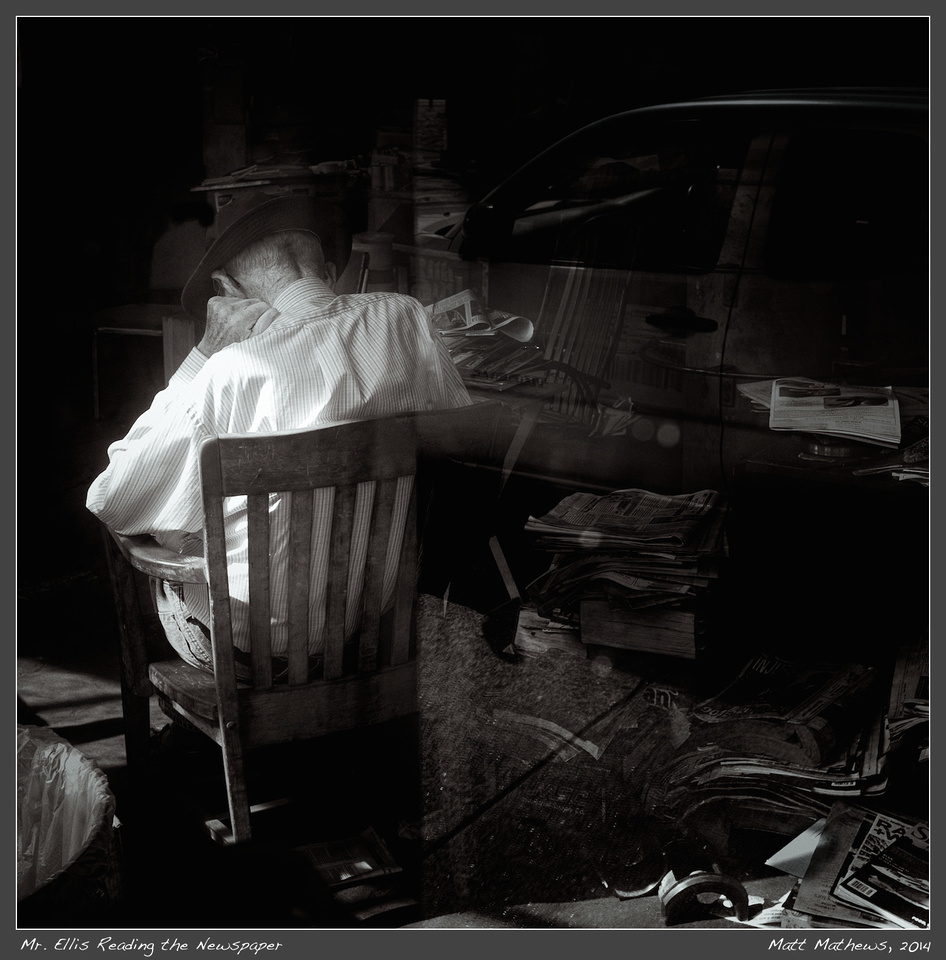

Mr. Ellis Reading the Newspaper

Mr. Ellis Reading the Newspaper

In the years that I have been photographing seriously, I have rarely had a second chance to correct a serious creative error. This week, I got such a chance.

In 2009, I had the honor of photographing inside The Ellis and Sons Iron Works located on the corner of Front Street and Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard in Memphis, Tennessee. Ellis and Sons is among the oldest, continuously operated businesses in Memphis, and despite profound economic shifts that have severely diminished the business, it survives. In 2009, I enjoyed spending a few hours inside the foundry, photographing the massive machinery and interesting textures, lines, and shapes that fill this old warehouse. I remember that around every turn in this old building were so many interesting things to photography that it felt overwhelming. Among the favorite photographs that I made that day in 2009 is this one of a piece of machinery used to melt metals for casting into molds.

My mistake in 2009 was failing to photograph Mr. William Ellis himself, the namesake and direct descendent of the founder of the business. I met Mr. Ellis that day, already then in or fast approaching his nineties, and he was among the most gracious and proud men that I have met. He has worked in this same factory since he was a fourteen-year-old boy. He toured me around the shop, telling me of the history of this family-owned business that an earlier Mr. William Ellis established in 1862 to cater to the boats carrying freight on the Mississippi River, one block west of the foundry. Mr. Ellis then gave me free rein to wander through his shop unattended. And yet, I never turned my camera to Mr. Ellis himself. I have regretted this oversight every time I review the collection of photographs of the industrial forms I made that day.

Today, I atoned for my creative sin. While walking in the South Main District of Memphis during the late morning hours, I wandered past the Ellis and Sons Iron Works building. As I did, my mind went back to 2009 and my failure to photograph Mr. Ellis. And suddenly, there he was, visible through a dirty old window of the foundry, surrounded by piles of newspaper and equipment and framed by reflections cast in the window. There he sat in soft midmorning light reading the newspaper as he probably does every day. And he did not see me.

First I photographed him from the front to reveal his face; and then it struck me that a far subtler photograph was to be had if I photographed over his shoulder, and just as I moved into position, he lifted his left arm and rested his hand on his neck. When I made the exposure, I knew immediately that I had the photograph that I have longed for for five years.

After I made the photograph, I considered going inside to ask if I might photograph him formally. For a moment, I worried about the clutter surrounding him in the portrait and thought a photograph made inside would be "cleaner." But then I realized that this clutter has surrounded him for the eighty years that he's worked in this building, and it is part of what defines him. So, I did not go inside. I knew that I had the photograph that I wanted. But more importantly, it seemed that going in and interrupting him would diminish the extraordinary manifested in this most ordinary of moments.

Photographers rarely get second chances, but on this day I did. And I am deeply grateful for having been in the right place at the right time.

Cheers, Mr. Ellis. Carry on with your daily routine. And thank you for a moment in which the ordinary was suddenly bathed in the extraordinary.

Photographs as Metaphors

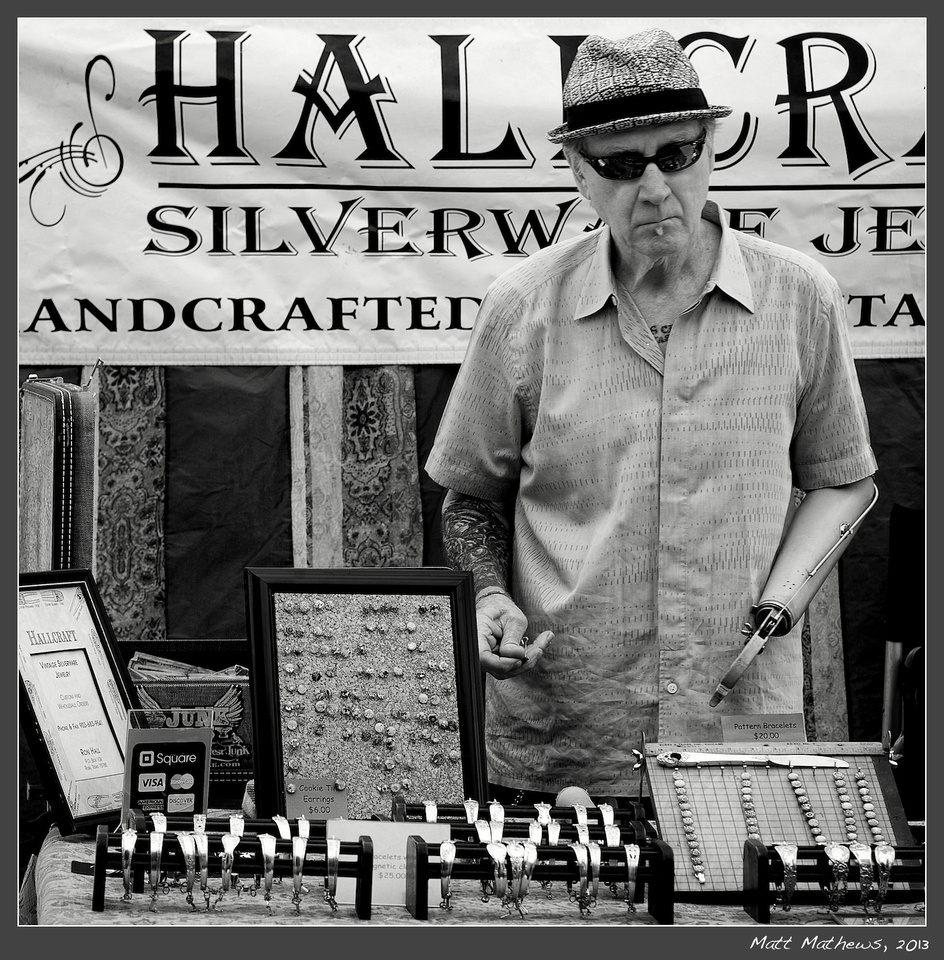

Jewelry Craftsman, Clarksdale, Mississippi, 2013

I have come to believe that the art form most similar to photography is poetry. The poet aims for an economy of words, subtracting all extraneous ones in the pursuit of highly concentrated meaning. Photographers do the same. We seek to concentrate meaning by the subtraction of all elements in a scene that might dilute it. And like the poet, we must embrace inherited forms for our creativity. Just as with the poet who chooses to write a haiku or sonnet, the photographer chooses to work within inherited structures, aesthetic forms, and visual traditions that place constraints on the creative act. Such constraints, however, far from stifling creativity, call it forth. And finally, like poets, photographers use rhyme schemes. Photographs hold our attention quite often because their visual elements curiously echo one another, creating a pleasing visual rhyme. In Jewelry Craftsman, for example, we might notice that the craftsman holds in his right hand a clip that faintly echos the end of his prosthesis. Or again, as we look a bit longer, we might notice the rhyme between the missing letter of "Handcrafted" and the craftsman's missing hand.

But most importantly, poems and photographs traffic in metaphors. Etymologically, metaphor is interesting. Metaphorein in Greek literally means "to carry over" or to "carry beyond," and here is a curious thing. Metaphors carry us over a gap between two worlds of meaning. And yet, in carrying us over, there remains an elusive beyondness to the new land of meaning that prevents us from fully occupying and domesticating it. Metaphors bring into view a great beyond, and they tease us by letting us visit and even touch it briefly but never own, possess, or fully control it. Metaphors, to borrow a phrase from the Hungarian photographer Brassai, "suggest rather than insist."

The late French philosopher Paul Ricoeur famously spoke of metaphors as having "a surplus of meaning," by which he meant that metaphors can never be fully translated into straightforward pedestrian prose without losing something in translation. When explanatory prose reaches out to grasp the meaning that metaphor throws out in front of us, its reach is never quite long enough. The metaphor eludes conceptual mastery, insisting on an element of indeterminacy and openness beyond exhaustive translation. This playful surplus of meaning is what holds our imagination even as it confounds the reductive impulses of the the mind. We get tangled up in metaphors, and in their bondage we find freedom and delight. In the swirling world of the metaphor, we touch levels of cognitive and affective meaning in ourselves and in the world that have hitherto eluded us.

Jewelry Craftsman is a visual metaphor. When I look at it, I am confronted by the fragility of human existence, by the power of beauty to embrace loss, tragedy, and brokenness in an act of redemptive transfiguration. I am confronted with the constant interplay of the organic and mechanical in modern life. I am reminded that much of life has an improvisational character where we must learn to make our jewelry with what's left over. Jewelry Craftsman throws out in front of us the tangle of our own loss and triumph, our own stubborn knots of brokenness, creativity, and new possibilility.

But look again at Jewelry Craftsman. It is at once less and more than all this. My hope is that it's worth more than a thousand words.

Voyeurism, Solidarity, and Queering the Camera

On Saturday, September 27, I attended the Midsouth Pride Festival and Parade in Memphis, Tennessee. This is my fourth time at this festival, and only now am I beginning to grasp more fully what it's all about.

Pride festivals and parades are about many things: celebration and defiance, excess and performance, sexuality and spirituality, costumes and authenticity, liberation and justice.

When one photographs at a Pride event, one can approach the task as either a voyeur or participant. I choose to be the latter. I seek to enter fully into the festival, and more importantly into the broader struggle of LGBTQ people. Participation is an act of solidarity rather than charity. Charity is merely the momentary, guilty conscience of the voyeur.

The way of solidarity involves forming deep, abiding friendships with LGBTQ people and other allies, nourishing and being nourished by a shared life that both transcends and includes the multitude of ways we are different from one another. It means coming alongside a marginalized but triumphant people, not as a self-appointed straight liberal savior, but as an empathetic friend who shares the burdens, the struggles, the victories, the defeats, the joys and laughter, the anger and pain. Solidarity means sticking around and finding your own life only when you lose it in the lives of others.

One of the gifts of solidarity is authenticity, and in the case of solidarity with my LGBTQ friends, it is an authenticity that regularly calls me forth from my own closets filled with false identities that are safe and comfortable. While the closets of LGBTQ people are often especially dark ones filled with toxic air that suffocates the spirit, most of us have closets of our own where we retreat and trade authenticity and flourishing for various false selves hell-bent on mere survival and unreflective social conformity.

When I photograph Pride events, it is a gesture of thanks and admiration to the LGBTQ community and its allies for empowering me to transgress with queer courage and drag-queen delight all those carefully guarded, arbitrary boundaries that masquerade falsely as natural and essential to my and society's wellbeing. My LGBTQ friends make me a better photographer and theologian, and in the end a better human being.

And it is to these friends that I say "thank you" with these 43 photographs. If you would prefer to see the photographs in the gallery or if your internet connection does not permit uninterrupted viewing of the slideshow below, click here.

Beauty, Whole and Broken

My exhibition of photographs, "Beauty, Whole and Broken" is on display in Founders Hall, Memphis Theological Seminary through December 10, 2014. The Artist Statement and a slideshow of the exhibited photographs appear below.

Artist Statement

“We should not merely run [our eyes] over [creatures] cursorily, and, so to speak, with a fleeting glance; but we should ponder them at length, turn them over in our minds seriously and faithfully, and recollect them repeatedly."

-John Calvin, Institutes 1.14.21

“Beauty, catch me on your tongue.”

-Andrea Gibson, “Birthday”

Faith is deliciously sensuous. It calls forth from us a long, loving look at the extravagant beauty of the world. Faith brings mindful seeing, a renewed attentiveness to the handiwork of God all around us. In faith, we are invited to attend to things small and large, fragile and threatening, with patience, delight, and awe. We are summoned to linger over particulars with heightened sensitivity and an expectation of surprise. Faith transfigures our casual seeing into the wonder-filled, wide-eyed gaze of a child. For Calvin, such seeing is an expression of gratitude, and when we fail at it, he judges us of guilty of "criminal apathy."

"Beauty, Whole and Broken" is a collection of photographs that invites us to acquit ourselves of the crime. These photographs celebrate two kinds of beauty. The first is whole beauty -- the beauty of pristine things free of defect and flaw. Such beauty is of things untouched by fallen human hands and free of tragedy, flaw, or brokenness. We see such beauty in the luminous blossoms of the dogwood, in a strand of seaweed floating aimlessly in dark waters, and in a moonrise over granite dells so strange in shape that we might mistake them for an alien world. To taste whole beauty is to taste the original goodness of God and the world and to be reminded that even though ours is but a small place in the world, it is a good place.

But even whole beauty gets broken. Wildfires ravage pristine landscapes. Here is another kind of beauty -- broken beauty. This is an improvised beauty that embraces tragic or flawed elements and transfigures them into something higher. We glimpse such beauty in the one-armed craftsman of hand-made jewelry whose hand holds a clip that echos his prosthesis. We see this beauty in the bliss of a boy riding a mechanical bull whose missing horn imperils the illusion. We see it in the bluesmen whose notes and voices squeeze beauty out of the depths of human suffering and anguish. To taste broken beauty is to taste redemption and to be reminded that God's beauty travels through the tragic rather than around it.

O Divine Beauty, "catch [us] on your tongue."

Why Black and White Photography?

Viewers of my photographs sometimes ask why I work in black & white more often than color. So let me offer an answer.

Black and white photography is abstraction. It relies on tonality, texture, and line to direct the viewer to what is essential in what is photographed. In suspending color, it asks something of the viewer. It asks you to work at seeing.

Black and white photography was born of necessity. It was the only medium available for the first hundred years after the first photograph was made in the late 1830's. But what was born of necessity has now become a choice for many photographers, myself included.

The choice to work in the black and white tradition is not unlike the choice of the poet who chooses to write poetry in the inherited forms of a haiku or sonnet when free verse is readily available. Like the haiku or sonnet, black and white photography brings a set of rules and formal structures that must govern the visual poetics of a picture. The photographer, like the poet, must embrace these rules and formal structures and regard them not as restrictions on creativity but as necessary conditions for it.

Black and white photography takes us back to elemental things. It invites the viewer to see the beauty of the weathered texture of the sunlit surfaces, the sculpturesque lines of the keel, and the elegant curves of the mooring ropes of a simple fishing boat.

Black and white photography is also a declaration that the photograph is an interpretation rather than a mere duplication of the world in front of the camera. Yet in its falsification, it speaks its own truth about the world.

I photograph in black and white because I want to see the world as it really is.

Edward Weston, California, and What's Worth Photographing

The great photographer Edward Weston once remarked that "everything worth photographing is in California." He was wrong, of course, and I believe he knew it when he said it. Weston casts a long shadow across twentieth-century photographic history. He was a mentor to Ansel Adams and founding member of the F/64 Group of west coast photographers most famous for their rejection of the movement of pictorialism that had prevailed in photographic circles at the turn of the twentieth century. Pictorialism sought to legitimate photography as an art form by imitating the aesthetic standards of painting. Held in suspicion for creating their images with a machine, pictorialist photographers sought to conceal the incriminating characteristics of a photograph by making it look like a painting. They smeared substances on their lenses to impart a soft, dreamy quality to their photographs; they printed on textured papers and smudged and scratched elements of the image to suggest the brushstrokes or textures of the paintbrush; and they often chose "classical," highly idealized, posed subjects that were intended to call to mind by way of allegory the eternal ideas, timeless values, common tropes of western art and civilization. All this was aimed at earning photography standing in the world of fine art.

Weston, Adams, and the members of the F/64 Group ultimately came to reject pictorialism because it was photography done with a bad conscience and because it sought to conceal the most powerful virtues of the photographic medium: its "straight" representation of the world as given to us rather than as idealized or modified by the human imagination. The camera rendered the world without artifice, and photography would have to stand on its own aesthetic merits. Led by Weston, "straight photograhers" embraced glossy, smooth photographic papers most unlike the textured or tinted papers of painters. They set the apertures of their view cameras to F/64, the smallest available aperture, which ensured that everything in the image was in sharp focus. Initially, Weston minimized his manipulations in the darkroom and refused to produce enlargements, favoring only 8"x10" contact prints to preserve maximum fidelity in tone, texture, and detail in the subject photographed. And perhaps most importantly, he turned his attention to form -- to the power of lines, curves, and tonal gradations in ordinary subjects all around him. His photographs were not to be allegories of otherworldly truths but celebrations of this-worldly beauty conveyed in the ordinary. They were a paeon to form, texture, and tonality sung in the voice of a new, "modern" aesthetic.

Weston refined his artistic sensibilities and techniques along the coast of California, with much of his work coming from Point Lobos not far from his home, Wild Cat Hill, on the Monterey Penninsula. As with Adams but to a lesser degree, California was a place of wildness and untamed beauty, and the rugged, unforgiving coastline was not subject to human artifice. If Adams celebrated the beauty of the Sierra, Weston celebrated the beauty of the coastline.

When I look at my Tidal Flow, Morro Strand State Beach, No. 2, I realize how growing up in the Central San Joaquin Valley of California positioned me geographically and artistically between Adam's Sierra and Weston's coastline. The more I photograph, the more aware I am that no one creates in a vacuum. We always create from within visual and aesthetic traditions whether we realize it or not. With the straight photographers, I value the world as it presents itself. The camera must be accommodated to the givenness of the world. My preference for black and white images belies my fascination with form, texture, and lines. I do not subscribe to the artist-as-genius fiction which assumes that artistic skill is an unlearned, native-born gift or burden that the artist is entitled to inflict upon the world. Photographs should not be about the inner life of the photographer; few things could be so boring. Photographs point in fleeting, halting, and partial ways to the beauty of the world. They are in invitation into the real beauty "out there" (in California and well beyond!). Beauty is not in the eye of the beholder; it is the metaphysical substratum of all that is. The question is whether we will pause to experience it.