Storefront Windows and Cognitive Flexibility

Wheel in the Sky, 2010

Wheel in the Sky, 2010

For the better part of the last decade, I have been photographing on and near Main Street in downtown Memphis, Tennessee. When I began photographing there, I wasn't clear what I was trying to communicate.

In discussing his own photography, Sam Abell has remarked that he often finds that he photographs "ahead of himself;" that is, his visual instincts and creativity impulses lead him out into the world to make photographs of particular subjects before he can understand or articulate why. I believe he's right; I, too, often photograph ahead of myself. Only later do I find words to explore what I was up to with the camera.

My attention has gradually settled on the kaleidoscopic reflections found in storefront windows. As these reflections mingle with the interior spaces and objects behind the glass, the scenes become intriguing, beautiful even, with their odd play of vibrant colors and juxtaposed elements. The scenes are often reminiscent of the surrealistic paintings of Salvador Dali or the collages of school children.

Wheel in the Sky represents one of my earliest moments of insight into the windows project. It was made on a winter day in 2010, and grey storm clouds were giving way to blue skies. As I looked up at a bicycle suspended in the window of a shop, I saw more than a bicycle. I saw an odd intermingling of nature and artifice, clouds and machine, bricks and blue sky. I sensed the oddity of it as well as its peculiar beauty.

Like other photographs in the collection, Wheel in the Sky offers resistance to our ordinary, habituated ways of seeing. We are trained to peer through windows to see what lies beyond, to home in on what really matters. Ours is a penetrating gaze that is quick to discard the ephemera in search of what is solid, stable, and fixed. It is a serious seeing, a seeing with purpose. Things are quickly sized up for their utility or market value. Our visual habits betray our drive for mastery, control, and use. These same habits also betray our casual disregard for wonder, intrigue, and curiosity and our neglect of that felt sense of mystery that wells up within us in the presence of surprising, transient beauty.

In the windows, things are tangled in reflections that are ungraspable, useless, and immaterial. The scenes are riddled with insubstantial forms, and they extol mere appearances above hard realities. Mastery yields to mystery, the practical to the imaginative, and possession to delight. They call for and awaken cognitive flexibility, a spiritual agility that bends gracefully toward wonder, curiosity, and openness.

And in the end, this cognitive flexibility, together with its attendant virtues of soul, may be a vital part of what rescues us from the rigidity, bitter alienation, and xenophobia that seem to animate a new strain of American fascism.

Welcome surprises and savor the strange. Look at the windows rather than through them from time to time.

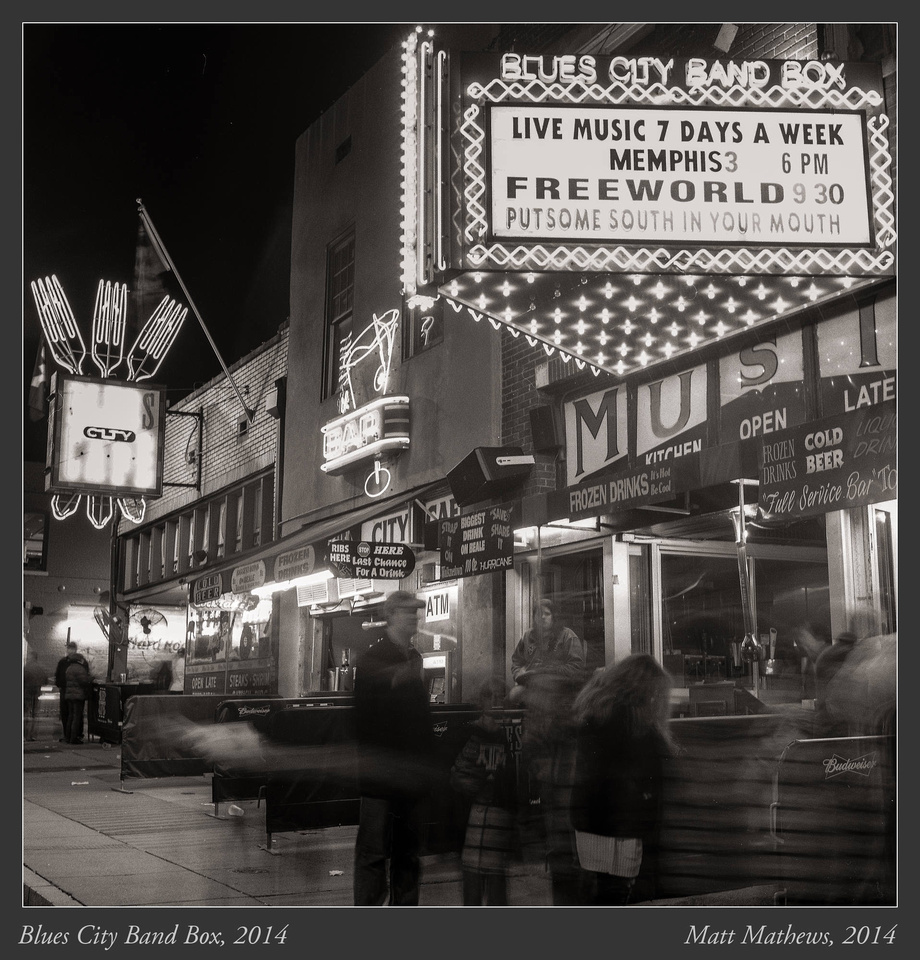

Purchase Prints of "Memphis by Night" or Other Collections

In anticipation of the holidays, I'm announcing the availability of prints from my "Memphis by Night" Collection. If you would like to purchase a print, please contact me ([email protected]). Please identify the photograph(s) you would like to purchase using the thumbnail number(s) visible in the online gallery.

I am offering the following purchase options for these open-edition, signed prints.

Large Prints

Mounted and matted unframed print for a standard 16"x20" frame: $75.00 (actual print sizes is 11.25"x11.25")

Mounted and matted print framed in either a 16"x20" or 18"x24" black gallery-style frame: $150.00 (actual print sizes are 11.25"x11.25" or 13.25"x13.25")

Small Prints

Mounted and matted unframed print for a standard 11"x14" frame: $40.00 (actual print size is approximately 7.75"x 7.75")

Mounted and matted framed print in an 11"x14" black gallery-style frame: $75.00 (actual print size is 7.75"x7.75")

Please allow 10 days for delivery. Order deadline for delivery by Christmas is December 15.

If your order requires shipping, I will simply add only the actual cost of shipping. Add an additional 5 business days to delivery time.

Finally, if there is a print from a different collection in my gallery that you'd like, I'd also be happy to do one for you at the prices listed above.

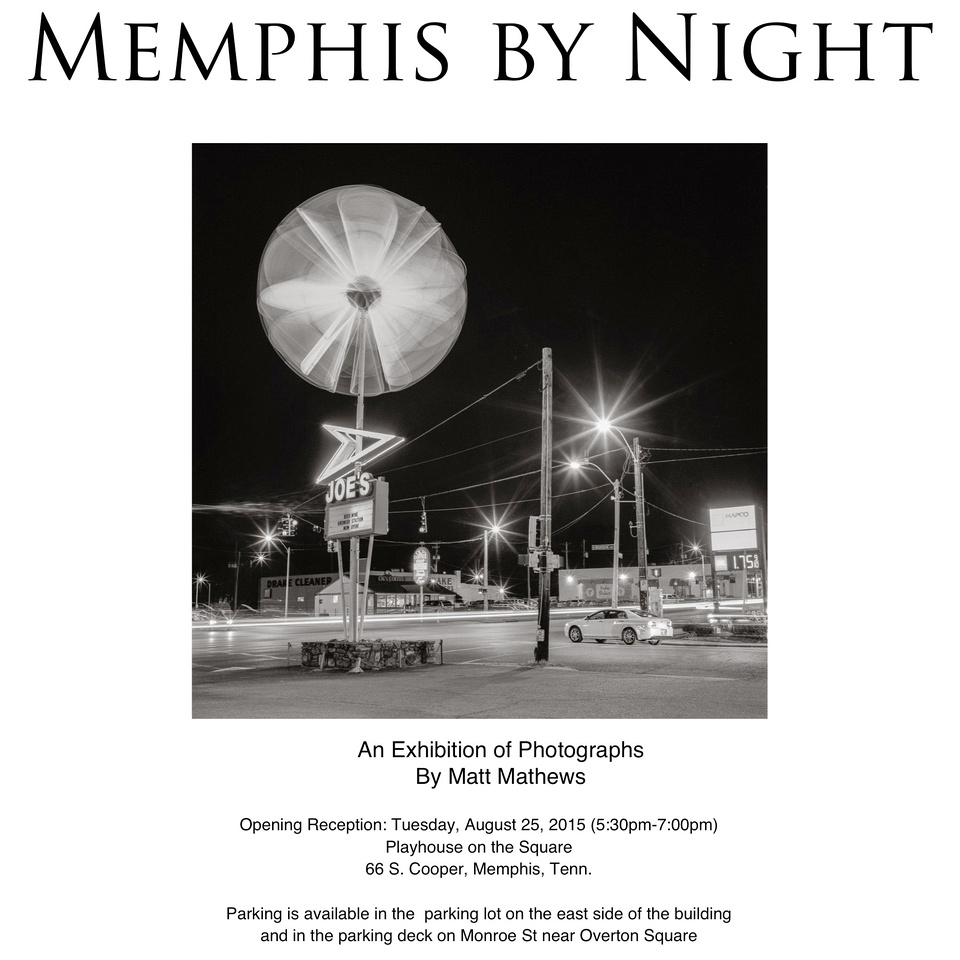

Exhibition and Reception for "Memphis By Night"

"Memphis by Night," my exhibition of photographs that explore our city after sunset will be open to the public from July 31 through September 12, 2015. The collection may be viewed in the first floor gallery at Playhouse on the Square. Details below.

The Artist Reception is Tuesday, August 25 from 5:30-7:00pm and is free and open to the public.

Reflections on Black Women, Funk, and Beale Street

Funk on Beale Street, 2015

I will never understand what it means to be a black woman in America, at least not fully. And I am not alone. But this fact does not exempt me from the obligation to try. Nor does it mean that I cannot come to understand at least something about it if I try really hard.

In Shoes That Fit Our Feet: Sources for a Constructive Black Theology (Orbis, 1999), Dwight Hopkins explores two polarities that exert a powerful influence on the lives of many African-American women. Borrowing from the colloquial discourse of black women, Hopkins names these polarities thing and funk.

Thing names all the forces of American culture that conspire to objectify black women, that work to erase their humanity and render them invisible except when we need them present to be exploited economically, sexually, and culturally. Thing happens when the ideology of whiteness constructs a black woman's identity into an over-sexed exotic other, a welfare queen, or a asexual Aunt Jemima whose nannying is as simple and sweet as tasty syrup on pancakes. Thing happens when we are unable or unwilling to see the myriad of successful black women who disrupt these cultural constructions. And thing happens when we explain away the success of such women as exceptional and thus anomalous, forgetting their names even as we make them "a credit to their race."

It's easy to internalize thing's lie. Toni Morrison and Alice Walker have taught us as much in The Bluest Eye and The Color Purple. The internalized lie shows itself in guilt, self-doubt, and a sense of defilement that wear away at the bodies and souls of black women. A healthy sense of one's worthiness and an appropriate love of self are paralyzed by the venom of shame and a sense of powerlessness.

Funk is hard for white people like me to understand. It seems so loud, so boistorous, and, well, just so black. It makes us uncomfortable. It does so because it protests and resists the stranglehold of our whiteness. Funk erupts in gesture, dialect, slang, art, and in the occasional wagging of a black women's finger at a condescending clerk, nurse, or theologian. Its roots are deep, reaching back to "sassing" the master on the plantation. It was and is resistance to thing. It is a stubborn insistence on somebodyness; a refusal to conform to white expectations for black being. It is soul. It is agency. It is an assertion of her genuine self over against the false constructions of her identity as welfare queen, over-sexed exotic other, and benign nanny. Funk is gospel, grace, and judgment wrapped into one.

But funk is protest in the form of a zesty celebration of life. It celebrates embodiment and soulful sexuality, redeeming them from white fantasy, fear, and violence. It celebrates slang, gesture, and rhythm, offering redemption from "respectable" speech and the politics of respectability required by thing.

Funk is fun. Funk is playful. Funk is parody. Funk piles atop male motorcycles and strikes an overdone, playful pose of parodied seduction and satirized femininity that unmasks the absurdity of our dangerous cultural myths. It's the exuberant, unpoliced celebration of the whole self as it triumphs over thing. If thing is death, funk is life.

Hopkins has helped me understand a thing or two about the experience of many African-American women. I don't fully understand, of course. And, if I'm honest, funk still sometimes makes me squirm a little. It's difficult to confront my complicity in thing as an upper middle class white man. It's much easier to deny thing's existence, insisting on the tired tropes of the importance of personal virtue and hard work abstracted from historical and social analysis. But it's even more difficult to muster some funk of my own to resist it.

In the end, Funk on Beale Street is an invitation "to play that funky music, white boy"* and by so doing deliver my white pigment from the ideology of whiteness that often enslaves it in its own kind of soulless thing.

-----------------------------

*"Play that Funky Music" was written by Rob Parissi and first performed by the band Wild Cherry in 1976.

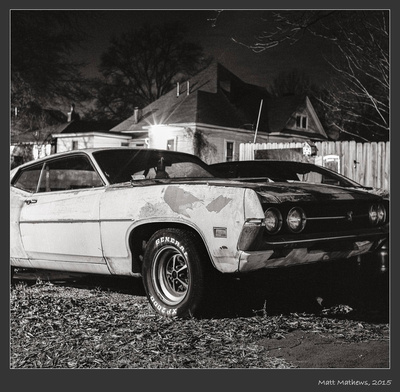

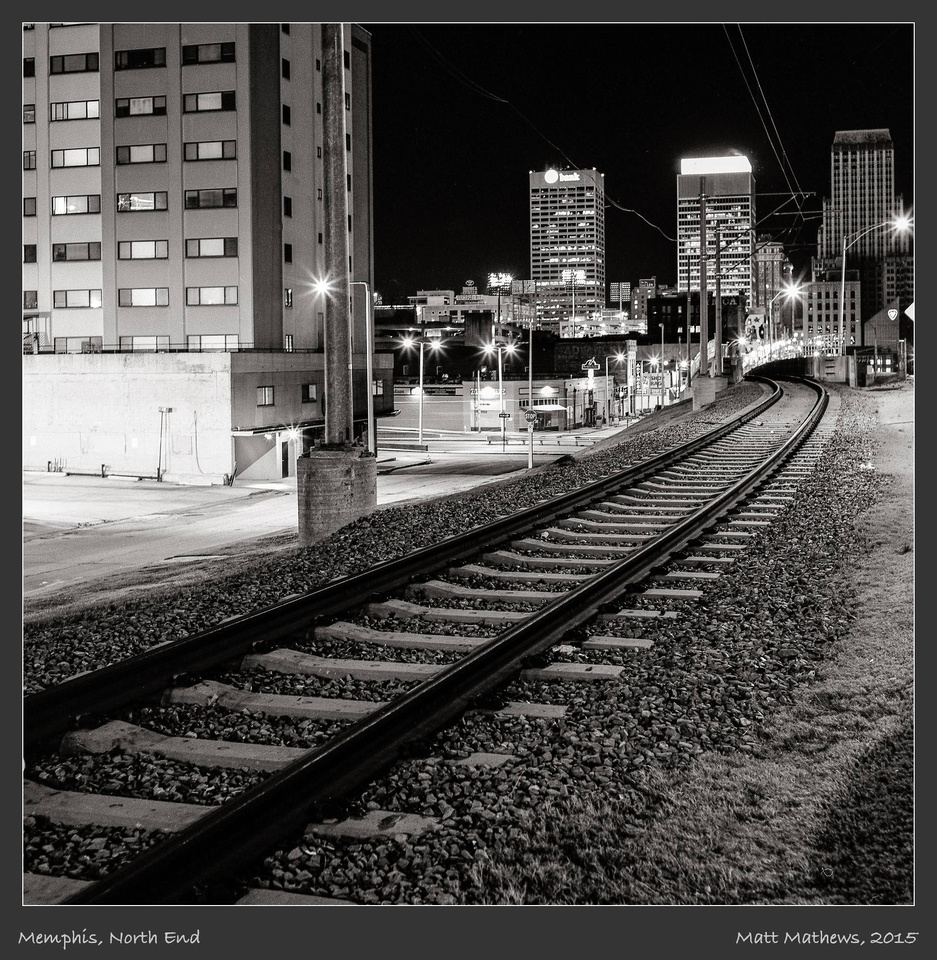

Reflections of a Flaneur: Memphis by Night

My current photography project, "Memphis by Night," is inspired by Brassaï, the great Hungarian photographer who photographed Paris at night in the early 1930s and eventually published a collection of these photographs as Paris by Night in 1932.

Paris had installed its first gas-lit street lights in 1828, the first city to do so, and with them Parisians redeemed the night for public life. Wandering the "City of Light" at night, usually alone but occasional with a friend or two, Brassaï grew fascinated by the dramatically different appearance of the city. The moody shadows, the uneven lighting created by street lights playing on surfaces of buildings and streets, and the moody, misty light diffused by fog captivated him. In the night, even the small public toilet kiosks that were then common fixtures along Parisian streets seemed like little enchanted castles. With them, the cobblestones, trees, and park benches became a dreamy, noir tableau.

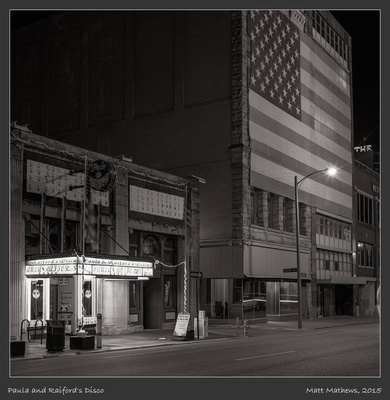

Paula and Raiford's Disco, 2015

Paula and Raiford's Disco, 2015

But it was not the city alone that changed at night. So did its inhabitants. Brassaï turned his camera on lovers embracing in the privacy of dark parks, prostitutes courting the attention of potential johns, and the invisible workers of the night -- butchers, delivery persons, rag collectors, police officers, street repair crews, and others whose work often prepared the city for life by day.

From the moment I first opened my anthology of Brassaï's photographs, I was intrigued. I had never really explored any city at night with creative or visual depth. And so, after living with Brassaï's work for several years, I decided to wander Memphis at night, and I decided to do so with an old medium format film camera from the early 1960s as fully manual and nearly as clumsy as Brassai's Voigtländer Bergheil camera.

Homeless Man and Architecture, Cannon Center, 2015

Homeless Man and Architecture, Cannon Center, 2015 Much like Brassaï, when I go out at night, I go as a flâneur -- a walking drifter, an aimless wanderer persistently available to whatever Memphis by night wants to reveal. I have ideas, hunches, and instincts that I follow, of course, but nothing is a sure bet, and there are always surprises and much improvisation. I wander dark alleys where I hear squeaking rodents and see chefs out smoking on their breaks. Other times I meet homeless people huddled in obscure corners or young professionals moving between bars, restaurants, and sporting events. Then there's the occasional security guard, underpaid and hungry for validation, who meets me with suspicion or excessive chattiness.

Much like Brassaï, when I go out at night, I go as a flâneur -- a walking drifter, an aimless wanderer persistently available to whatever Memphis by night wants to reveal. I have ideas, hunches, and instincts that I follow, of course, but nothing is a sure bet, and there are always surprises and much improvisation. I wander dark alleys where I hear squeaking rodents and see chefs out smoking on their breaks. Other times I meet homeless people huddled in obscure corners or young professionals moving between bars, restaurants, and sporting events. Then there's the occasional security guard, underpaid and hungry for validation, who meets me with suspicion or excessive chattiness.

Sometimes people express interest and talk to me, but mostly they ignore me. Some look quizzically in the direction where my camera is pointed, puzzled and wondering what on earth could possibly be worthy of a picture. They are puzzled because they are still seeing and living as day people in the night world.

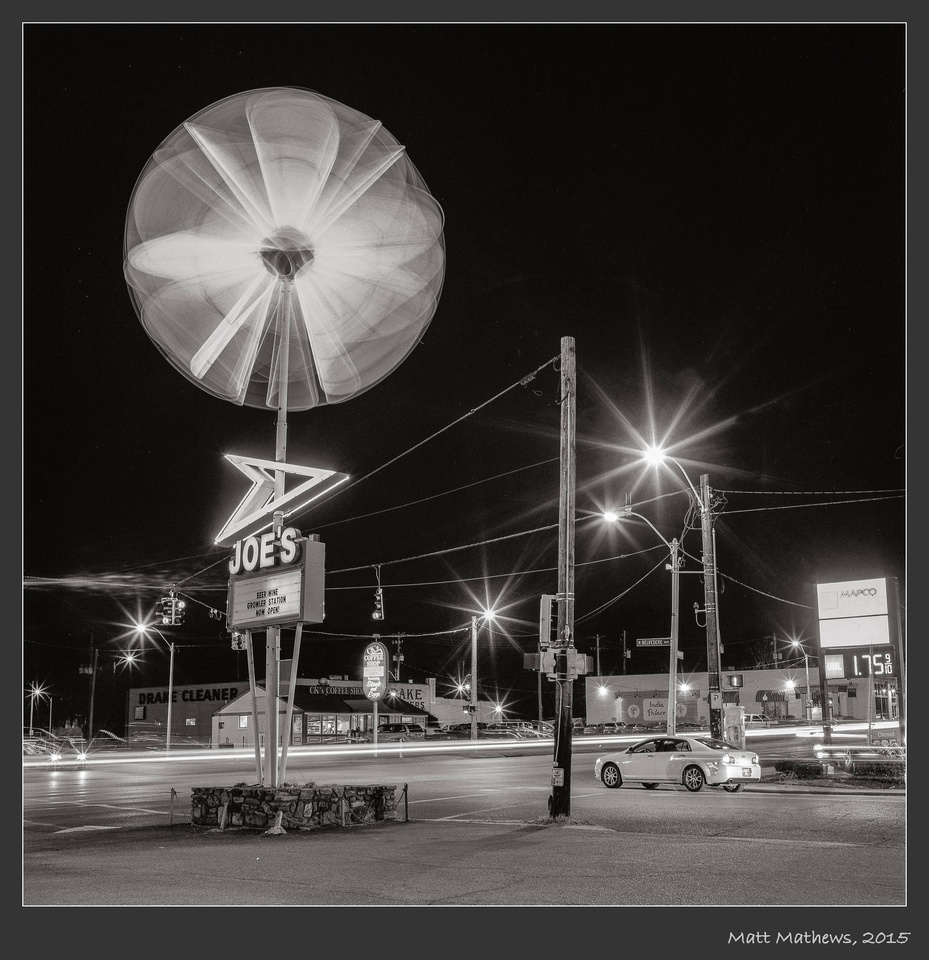

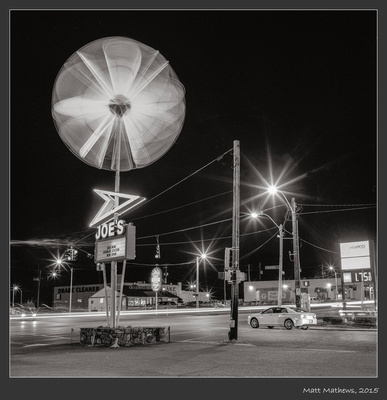

Sputnik at Joe's Liquor, 2015

Sputnik at Joe's Liquor, 2015 With "Memphis by Night," my aim is not merely to imitate Brassaï. I have focused far less on the people and far more on the cityscape of the night. I am especially intrigued by the way the long exposures required by night film photography capture the blurred movement of people, cars, water, spinning signs, and public art. Such movement did not seem to interest Brassaï. And in an age in which the camera has become a suspicious instrument of universal surveillance, I cannot take the camera into bars, restaurants, or hotels to photograph people as Brassaï did eighty-five years ago. Night-lit architecture calls me instead.

With "Memphis by Night," my aim is not merely to imitate Brassaï. I have focused far less on the people and far more on the cityscape of the night. I am especially intrigued by the way the long exposures required by night film photography capture the blurred movement of people, cars, water, spinning signs, and public art. Such movement did not seem to interest Brassaï. And in an age in which the camera has become a suspicious instrument of universal surveillance, I cannot take the camera into bars, restaurants, or hotels to photograph people as Brassaï did eighty-five years ago. Night-lit architecture calls me instead.

In the end, though, I have come to share Brassaï's insight, tinged as it is by surrealism, that "[n]ight does not show things, it suggests them. It disturbs and surprises us with its strangeness. It liberates forces within us which are dominated by reason during the daytime."*

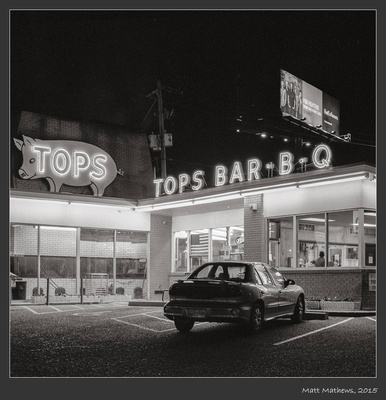

Tops Bar-B-Q, 2015

Tops Bar-B-Q, 2015

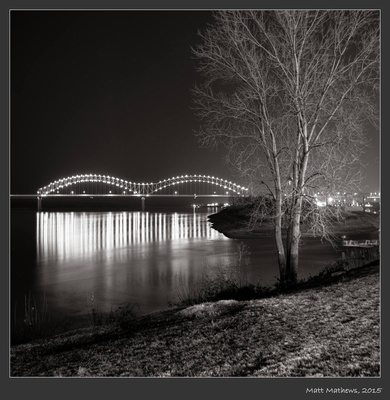

Mississippi River and Hernando DeSoto Bridge, 2015

Mississippi River and Hernando DeSoto Bridge, 2015

----------------------

*quoted in Jean-Claude Gautrand, ed., Brassai: Paris (Koln: Taschen, 2008); p. 32

The Windows of Simpson UMC -- Buy the Book

My book of 36 photographs of the the stained-glass windows of Simpson United Methodist Church, Evansville, Ind. is available for purchase online. See details below. You may also download a free E-book version below.

There are three purchasing options:

Option 1: An 8” x 10” Soft Cover Book available for $24.49 plus shipping. Click Here

Option 2: An 8” x 10” Hard Cover Book available for $36.49 plus shipping. Click Here

Option 3: A 13” x 11” Hard Cover Book available for $60.19 plus shipping. Click Here

Free E-Book:

To download the free E-Book version, which is great for tablets such as iPad or Kindle, click below. Since tablets vary, I cannot supply viewing instructions. Your tablet will need a PDF-reader program, and most have one already installed.

If you are using an iPad, click on the link below, download the file by touching the download icon (downward facing arrow at bottom right of screen). Once the E-book opens in your browser, touch in the upper right of the viewing area and you can transfer the E-book to the iBooks app and it will be viewable as a book in your library.

Click Here to Download Free PDF E-Book

The content of the book is the same across all print versions and E-Book versions.

The Allure of Film in the Digital Age

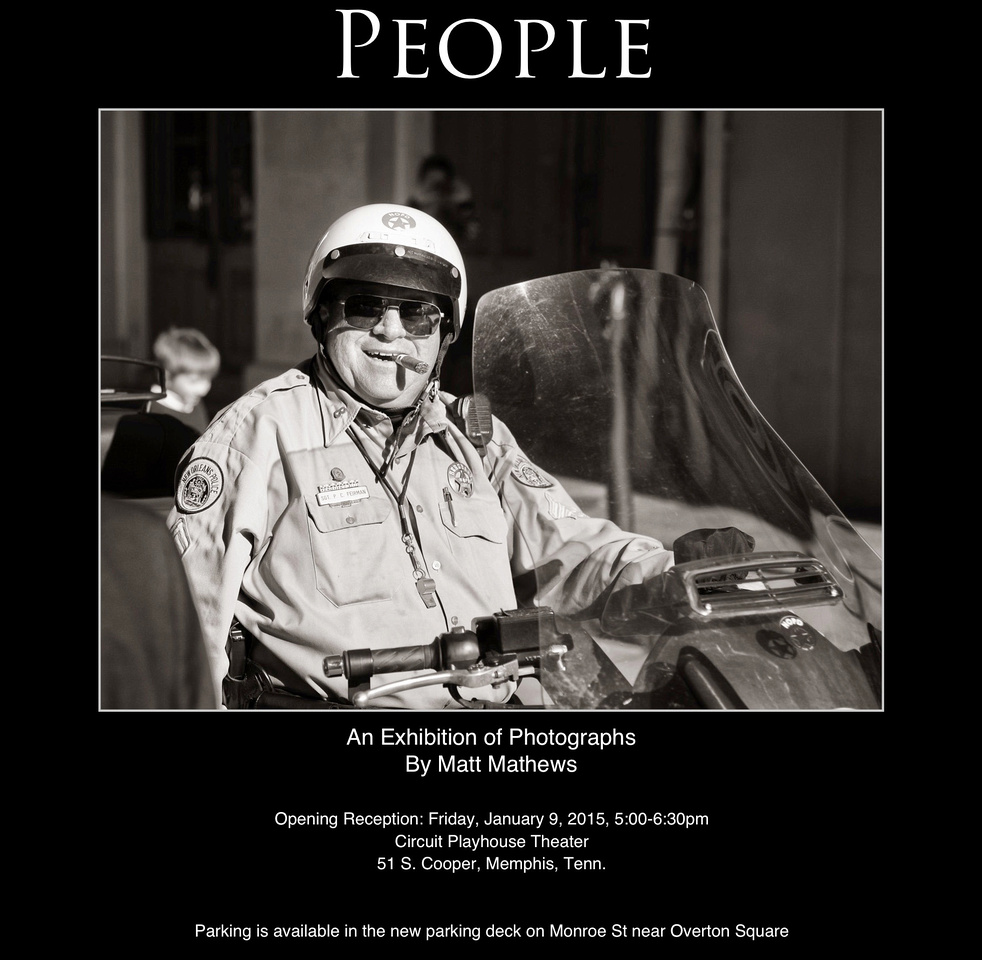

Invitation & Artist Statement for "People"

"We're born naked, and the rest is drag."

-- RuPaul, Drag Queen

Beauty, Cows, and Gnats

In Lawrence and Meg Kasden's 1991 film "Grand Canyon," there is a scene in which Mack, a wealthy lawyer, and Simon, a working class tow truck driver are discussing the Grand Canyon. Part of their exchange follows.

Simon: [sighs] When you sit on the edge of that thing, you just realize what a joke we people are. What big heads we got thinking that what we do is gonna matter all that much. Thinking our time here means diddly to those rocks. It's a split second we been here, the whole lot of us. And one of us? That's a piece of time too small to give a name.

Mack: You trying to cheer me up?

Simon: Yeah, those rocks are laughing at me, I could tell. Me and my worries, it's real humorous to that Grand Canyon. Hey, you know what I felt like? I felt like a gnat that lands on the ass of a cow that's chewing its cud next to the road that you ride by on at 70 miles an hour.

Mack: [laughs] Small.

We human beings often suffer from delusions of grandeur, assuming that we are the measure of all things. We labor under the illusion that our petty conflicts and triumphs are the metric of meaning in the universe. We imagine a world that exists solely for us, and we even refashion God into a cosmic sugar daddy who dotes over us, waiting to shower us with prosperity. But this small world with its even smaller god is an illusion.

It is very difficult to maintain this illusion when you sit on the edge of the Grand Canyon or hike in the deserts of the Southwest. In such places, we feel acutely our smallness and sense the landscape's inhospitality to human life. There is rarely water to drink. The sun scorches the skin. The wind drives fine dust into eyes and camera lenses. There is little shade. And then there are the rattlesnakes, scorpions, and tarantulas. Such places were not made for us. We are aliens in a foreign land. The God of this place is far more interested than we are in things other than us.

And yet, such wildness is terrifyingly beautiful. Such beauty transforms rather than entertains us. It tears loose our desperate, controlling grasp on ourselves and the world. It topples our little god. Such beauty dislocates us. Then it relocates us in a new world governed by a vast and different economy of meaning. It frees us to be gnats on a cow's ass as the cosmos goes speeding by at seventy miles per hour.

This belittling power of beauty is not the same as the petty belittling we do to one another as human beings. It does not erase our or another's humanity. To be small in a big world means that there's room for all. Beauty frees us to be fully, authentically human together.

Poet Muriel Rukeyser reminds us that "the universe is made of stories, not of atoms."* Beauty narrates a new story, a grand new epic with a new plot, new values, and new characters. Where we once worked anxiously to fit episodes of beauty into the big story of our lives, we now find that our lives are but small episodes in the grand epic of beauty that envelops them and all that is.

We are saved by smallness.

-------------------------------------

*Muriel Rukeyser, "The Speed of Darkness" (1968)

Deliverance from Temptation

Photography is my discipline for learning to be fully present to the world. When I take up the camera, I go exploring, tuning my senses to things that I might otherwise pass by in busyness and habit. It is an act of devotion to the real that frees me from constricted awareness and bondage to the illusions that so easily creep into daily life. It has taken quite awhile for me to arrive here, and along the way I have succumbed to a few temptations.

When I began photographing, I fell for the temptation of believing that there was a perfect camera, lens, or tripod which, if I found and bought it, would catapult my pedestrian photographs to greatness. And surely, there is a benefit to finding the right gear that suits your photographic style. To make good photographs, you need the right tools the same way a master woodworker needs the right tools to make great furniture. But camera gear does not make good photographs. Attentive photographers do.

I next fell for the temptation of believing that I could only make good photographs in exotic, picturesque places. I've walked along many miles of desert, forest, and beach, and I've made some good photographs along the way. To make good photographs, you regularly need the stimulation of new environments that evoke wonder, delight, and experimentation. But picturesque places do not make good photographs. Attentive photographers do.

And finally, I succumbed to the temptation of believing that strict adherence to rules of graphic design and composition would transform my photographs into great ones. So, I learned the rule of thirds, mastered the color wheel, faithfully sought out leading lines, and attuned myself to the siren song of the s-curve. And I learned that such design and compositional techniques do, in fact, enhance the visual poetics of my photographs. But such techniques do not make good photographs. Attentive photographers do.

Tools, travel, technique -- these are things that belong to what the ancient collection of Taoist writings known as the Chuang-tzu calls Little Understanding. Little Understanding is largely technical in nature and it is indispensable to creativity. But there's another kind of knowledge, the kind the Chuang-tzu calls Great Understanding. Great Understanding is creative vision born out of unconstricted attentiveness to one's environment. It is intuitive, unforced, spontaneous, and responsive to surprise. It is attuned to the mystery in the ordinary. Great Understanding involves heightened awareness of the evanescent and fleeting character of each moment of existence, and it lingers there, seeking not to own, possess, or control things. It lingers there to participate in and enjoy communion with things, but then lets them pass away as they inevitably must.*

I was reminded of the importance of Great Understanding again this week when I walked out to my car on the driveway. In the ten-second walk from my front door to the car, I was struck by the sullen, grey morning skies and the piles of leaves that the wind had blown into my front yard. I noticed the raindrops from early morning still on some of these leaves, and I was especially intrigued, for reasons I cannot fully explain, by the ginkgo leaves. And so, I reached for my camera and lost myself for an hour in the Great Understanding of the leaves.

Raindrops on a Ginkgo Leaf is one morning's triumph over old temptations and a savoring of Great Understanding.

-------------------

*I am indebted to Philippe L. Gross and S.I. Shapiro's The Tao of Photography: Seeing Beyond Seeing (Berkeley: Ten Speed Press, 2001; pp. 10-12) for this discussion of Little and Great Understanding.

R.I.P Yolanda

Last Saturday, I was combing the backroads of northwest Mississippi, looking for worthy photographs. This is the land of the Mississippi River Delta, and it is flat, low, fertile earth nourished over the years by the floodwaters of the Big Muddy. It is the land of King Cotton. It was once the land of slavery and unspeakable suffering. It is the land over which southern and northern troops moved during the Civil War. It is a land that bears the marks of its history in the still wide gap between black and white.

As I approached an intersection of two country roads, I spotted a roadside memorial to Yolanda, who died tragically in an automobile accident. Like most of us, I have seen many such roadside memorials, especially in the American Southwest where they are known as descansos, "resting places," and can be traced back to the centuries-old, Hispanic-American practice of marking the landscape with memorials wherever weary pallbearers briefly set down the casket on their long walking journey to the burial site.

I know virtually nothing about Yolanda, except that she died too young and died tragically on this little patch of flat and fertile land that has already known too much suffering in American history. I was moved by the austerity and simplicity of this handmade marker. The little angel figurine at the base of the cross has begun to dissolve and crumble in the elements. And with time, storms, and winds, the paint will fade and the wooden cross will fall over and disappear into the soil.

RIP Yolanda is someone's protest against private grief. It is a stubborn refusal to confine grief to the church, cemetery, or home. In a North American culture that denies death and often covers over its tragedy with embalming fluid, makeup, and tidy, otherworldly religion, RIP Yolanda takes us to the public place of senseless tragedy, the place where a particular young life was lost in a patch of dark Delta dirt. Set against the flat, wide, almost horizonless expanse is this place of particularized loss and grief, so poignant and intimate it goes only by a first name. Here is a public commingling of memory, sorrow, and warning to others traveling these isolated roads. If there is genuine redemption in this place, we struggle to find it.

What troubles us about RIP Yolanda is the lack of information surrounding it. We want to fill in the gaps, weaving together a possible biography and coherent account from a million loose threads of obscure clues and gross generalizations snatched up in a quick drive through of the nearby town. We speculate about the cause of the accident that killed her. We wonder if she or another party was to blame. We imagine speeding, drunk, sleepy, or preoccupied drivers. We want to sort out the sheep and the goats, the virtuous from the villains. We long for a morality tale that will provide an ersatz redemption for the whole damned thing. But none is given.

In the end, RIP Yolanda sets a question mark against all the easy exclamation points that punctuate our morality tales. And paradoxically, that may well be what redeems the tragedy, freeing Yolanda and us from easy answers, religious bromides, and morality tales too good to be true. Perhaps then, and only then, can we say with the ancient Hebrew writer, "Though God slay me, yet I live."

Making a Mountain "Look How it Feels"

In April 1927, Ansel Adams spent a day hiking up toward Half Dome in Yosemite. The trip was long and hard, and by the time he arrived at his final destination, he had only two unexposed glass plates left. Once at the Diving Board, a small rock protrusion below the face of Half Dome, he was overwhelmed by the beauty and immensity of the sheer granite wall towering over him. As he set up his view camera and readied it for the exposure, he realized that the photograph he was about to make would not communicate the experience of that moment. The photograph might faithfully duplicate the shapes, textures, and landscape, but it would not capture the experience of being overwhelmed by this massive monolith that in some ancient past had lost half its face in an apocalyptic crash of rock.

Adams later said that what he wanted was to "make it look how it felt." A straight exposure could not do that. So, Adams reached for his heavy red Wratten A filter, which dramatically darkened the surrounding sky and much of the face of the granite. This creative choice imparted drama and awakens in viewers a sense of the monolith's foreboding presence. The resulting photograph, Monolith, the Face of Half Dome, has a gothic and ominous quality that unsettles us even as it lures us. It retains this power despite the damage to the negative from the 1937 fire in Adam's darkroom that requires the prints to be cropped tightly at the top.

In early 2009, I was photographing in Yosemite during an early spring storm. I approached Half Dome and stood alone in the meadow beneath it, watching as the clouds drifted across it, sometimes revealing and other times concealing its surfaces and details. As I watched, gusts of wind lifted flurries of snow off its face and swirled them beautifully around the granite. Watching this primordial dance of granite, ice, clouds, and wind, I felt the mountain.

When we feel the mountain, we feel our own smallness. We are reminded that we are neither the measure nor the measurer of all things. We realize that we are measured by forces beyond ourselves, forces that both bear us up and bear down upon us. Such experiences deliver us from our exaggerated sense of our indispensability to the cosmos.

This sobering sense of our smallness opens the possibility of living more joyfully. It permits us to be creatures again unburdened by graceless perfectionism. It beckons us to embrace our fragility and limitations, and to love and be loved through them. It calls forth compassion for ourselves and all other creatures in the face of our and their partialities.

Storm over Half Dome asks you to feel the mountain.