Sampling Ernest Withers's "I Am A Man"

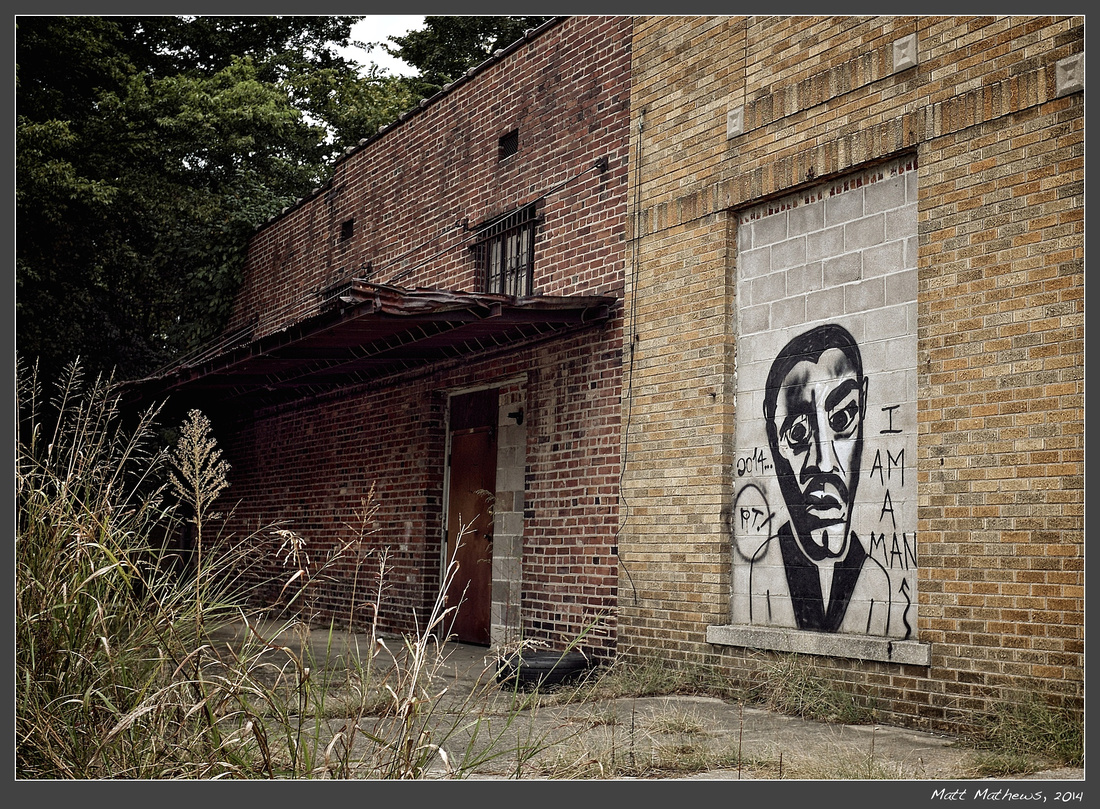

Ode to Ernest Withers, 2014

I knew Ernest Withers's photographs long before I ever knew it was he who had made them. Withers (1922-2007) was a photographer based in Memphis, Tennessee who photographed celebrities. But most importantly, he was one of the premiere photographer of the Civil Rights Movement. Withers's images are for the Civil Rights Movement what Matthew Brady's images are for the Civil War, what Ansel Adams's are for Yosemite, or Dorothea Lange's are for the Great Depression. Withers enjoyed unparalleled access to Martin Luther King, Jr. and other civil rights leaders, and he knew well the power of photography to strike at the American conscience and exert moral suasion. If King was the preacher, the wordsmith who moved a nation, then Withers was the seer whose photographs cast in silver tones the concrete, deeply intimate nature of the struggle as felt by African Americans.

Withers's photographic corpus of the Civil Rights Movement is very large, and in photograph and photograph we see a master of composition, timing, and exposure. In an age in which cameras often lacked light meters and lenses had to be focused manually, Withers always managed to get the iconic photograph. His technical abilities, though, were in service of a deeper vision. While his vision included photographing the large scale events of the movement, his brilliance, in my judgment, lay in his capacity to depict the struggle as it played out on a very intimate, human scale. Many of his images concentrated the struggle in a single individual or small group of people, often keenly focused on body language and facial expression amidst the palpable absurdities of daily life in a segregated society. We see these motifs in his Martin Luther King Resting on a Bed and in No White People Allowed in Memphis Zoo Today; or in one of my favorites, Father with Daughter in Stroller (1961).*

But Withers's most famous photograph is I Am a Man (1968). This photograph depicts the sanitation workers gathered outside Clayborn Temple on the corner of Hernando Street and Linden Avenue (now Martin Luther King, Jr. Boulevard) in downtown Memphis preparing to march. Few photographs express with such poignancy the personal as well as political nature of the movement. This was no mere political movements for rights, power, and equality; it was a spiritual movement demanding full personhood, and yes, even full manhood in the over-"boyed," segregated South.

This past Sunday, I went down to Clayborn Temple, now a boarded-up, for-sale shell of a building. It was often here that King delivered his speeches, huddled with his inner circle of leaders to plan strategy, and it was on this corner where the marchers gathered to begin their protests. It is sad to see this old African Methodist Episcopal Church building in such a state of decay. I went looking for a photograph but came away with none. It was a disappointing photographic outing.

As I left Clayborn Temple, I drove east on Vance Avenue, and several blocks up from the church I saw the scene depicted in my Ode to Ernest Withers, 2014. It took a moment to realize what I was seeing. When I did, I drove around the block for a second look. This time, I stopped and made the photograph, sensing acutely the connection between this bit of graffiti on the wall of a unimpressive vacant building and Withers's I Am a Man, made forty-six years earlier just a few blocks away. My photograph samples the lyrics of I Am a Man, but it does so at secondhand. I am after all merely sampling the lyrics of the graffiti artist who first sampled Withers's lyrical I Am a Man.

This sampling, of course, bears witness to the ongoing power of Withers's initial image. In I Am a Man, we feel the Civil Rights Movement. We see that while it was about rights, power, and equality, it was also about asserting, celebrating, and embracing one's own somebodyness in a world that daily tried (and tries) to erase you into nobodyness. It is here that we can see that before the Civil Rights Movement was a political movement, it was a spiritual movement born out of the Black Church and borne along by it.

When secular historians are tempted to overlook this fact, analyzing the movement only as a series of well-played political stratagems, we have the witness of Ernest Withers and a graffiti artist to lead the protest. Before Withers or the sanitation workers were "political players," they were "men."

*These titles of the photographs were not assigned by Withers; I have simply created them for purposes of this post.

Comments

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

(4)

September (4)

(6)

October (6)

(4)

November (4)

(2)

December (2)

|

(2)

January (2)

(1)

February (1)

March

April

(1)

May (1)

June

(1)

July (1)

August

September

(1)

October (1)

(1)

November (1)

(1)

December (1)

|

January

February

(3)

March (3)

April

May

(1)

June (1)

(4)

July (4)

(2)

August (2)

September

October

November

December

|

January

(1)

February (1)

(2)

March (2)

April

May

(1)

June (1)

July

(1)

August (1)

September

(1)

October (1)

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

(1)

April (1)

May

June

July

August

September

(1)

October (1)

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|