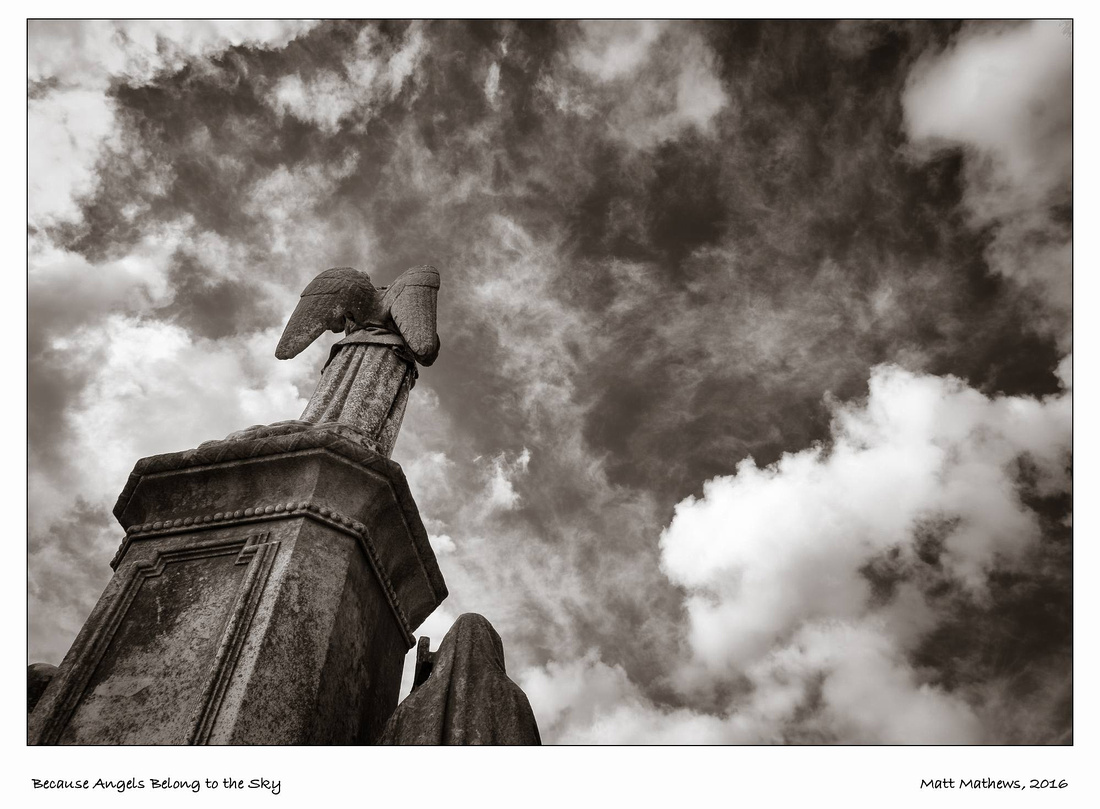

Because Angels Belong to the Sky

Because Angels Belong in the Sky, No. 2

Because Angels Belong in the Sky, No. 2

During 2016, I am serving as the David McCrosky Photographer-in-Residence at historic Elmwood Cemetery in Memphis, Tennessee. I have photographed at Elmwood for many years, but not with the frequency or intensity that now accompany my role there.

Elmwood Cemetery is many things. It is the resting place of countless citizens of the city, many of whom shaped its life deeply and even more who did not. This is no indictment of the latter, but its own kind of praise.

When I walk among the eighty acres of statuary at Elmwood, I find myself pulled in two directions. I am first drawn to the large, exotic statuary inflected with a heavy Victorian accent -- towering angels, childlike cherubs, angelic nymphs, stern-faced busts, inscriptions of florid prose and sacred verse. There is even a lexicon of symbols, garlands, flowers, obelisks, pillars, and cisterns that translate into stone the nineteenth-century language of death. It is a beautiful sight to behold, and a photographer's playground.

And yet, there is another side to walking at Elmwood that draws me as well. It involves seeing the gravestones of the average people, the ordinary folk whose graves are easily overlooked amid the extravagance of the Victorian garden with its hovering flock of angels. These are the gravestones of infants and children, often small and nameless, bearing only the word, daughter or son, or in some cases, only two initials. And then there are other gravestones, many broken and fallen, whose letters have become unreadable, worn smooth and indistinct by a hundred or more years of weather. And still again, there are the more recent, plain gravestones bearing only names and dates, as noticeably short on sentiment as they are on aesthetic appeal. It is easy to walk past these rather plain, functional memorials in search of the angels, generals, mayors, Civil War soldiers, Memphis's first black millionaire, and the martyred Episcopal nuns of the yellow fever epidemic of 1878.

This visual tension created by the variety of memorials awakens ambivalence in me. The most ornate gravestones and memorials are there to coach our memory about the people at rest beneath them. Such coaching, of course, is as notoriously lopsided as the markers themselves, many of which, like little leaning Towers of Pisa, have settled with time and now stand awkward and crooked. If we are honest, we know that these folk were not as angelic as the stonework above them suggests. They trafficked as much in power as in virtue. And yet, we or their loved ones prefer to re-remember them angelically, at least for awhile, until grief is far enough distant to allow for honesty.

But then there are those ordinary markers of the average folk, the graves of a sort of blue-collar dead people. Their gravestones coach us less, leaving us only with naked facts, a name with only the dates of birth and death etched artlessly on unadorned stones that look mass produced. Perhaps these are the more honest memorials, seeking only to mark an ordinary life lived and lost. They make no bid at angelic re-remembering. There is no effort to win for the ones below a redemption from all ambiguity and ordinariness. Unlike the large crypts and towering memorials that punctuate the cemetery around them, these smaller, plain markers seem to make no claim at immortality through stone. But surely, the lives of those beneath them were as full as the lives of the white-collar dead people who seem to hold them hostage in the cemetery. Surely their loves were as deep, their hopes as intense, their joys as real, their suffering as intense, and their families as important as those of the angels.

When I walk and photograph at Elmwood, I am drawn to both kinds of markers. As a photographer, I am drawn to the memorials adorned in Victorian excess, desperately seeking to coach our memory of the dead and achieve for them a kind of immortality in stone. I need them because I know that the same longing for recognition and permanence and the same temptation toward antiseptic memory well up in every human heart, my own included. As a theologian, I am drawn to the plain markers of the average people, for they offer a more realistic assessment of our days and lives. There is no attempt to accomplish in stone what they did not accomplish in life. They lived and loved, worked and played, and celebrated and lamented like I do. And then they died. And so will I.

As lovely as the angels are, we are not them. We belong to the earth below with all of the ambiguities, possibilities, and partialities ingredient in ordinary flesh.

In the end, it is only the angels who belong to the sky.

Comments

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

(4)

September (4)

(6)

October (6)

(4)

November (4)

(2)

December (2)

|

(2)

January (2)

(1)

February (1)

March

April

(1)

May (1)

June

(1)

July (1)

August

September

(1)

October (1)

(1)

November (1)

(1)

December (1)

|

January

February

(3)

March (3)

April

May

(1)

June (1)

(4)

July (4)

(2)

August (2)

September

October

November

December

|

January

(1)

February (1)

(2)

March (2)

April

May

(1)

June (1)

July

(1)

August (1)

September

(1)

October (1)

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

(1)

April (1)

May

June

July

August

September

(1)

October (1)

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|

January

February

March

April

May

June

July

August

September

October

November

December

|